- Finding a voice: Chinese art songs

- Two rivers and a wall (I): The Yellow River 黃河

- Two rivers and a wall (II): The Yangtze River 長江

- Two rivers and a wall (III): The Great Wall 萬里長城

- All about Confucius

- Chinese Poetry (I): Classic of Poetry 詩經

- Chinese Poetry (II): More about “Guanju”

- Chinese Poetry (III): Songs of Chu 楚辭

- Chinese Poetry (IV): “Song of the Yue Boatman” 越人歌

- Chinese Poetry (V): Han and Jian’an

- Chinese Poetry (VI): Transition and transformation

- Chinese Poetry (VII): Tang poetry

- Chinese Poetry (VIII): Three Refrains of Yangguan 陽關三疊

- Chinese Poetry (IX): Ci—Lyric verses

- Chinese Poetry (X): The Great River Flows Eastwards 大江東去

- Chinese Poetry (XI): Autumn Sentiments 聲聲慢

- Chinese Poetry (XII): A Love Song 卜算子

- Chinese Poetry (XIII): Turning Point

- Chinese Poetry (XIV): Verses of Red Beans 紅豆詞

- Chinese Poetry (XV): Revolutions

- Chinese Poetry (XVI): How Can I Help but Think of Her? 教我如何不想她

- Chinese Poetry (XVII): Chance Encounter 偶然

- Musical Settings (I): Introduction

- Musical Settings (II): Words, Tones and Music

- Musical Settings (III): Diction

- Musical Settings (IV): “The Great River Flows Eastwards,” The Song

- Musical Settings (V): “I Live Near the Headwaters of the Long River,” The Song

- Musical Settings (VI): Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅 and Yi Weizhai 易韋齋

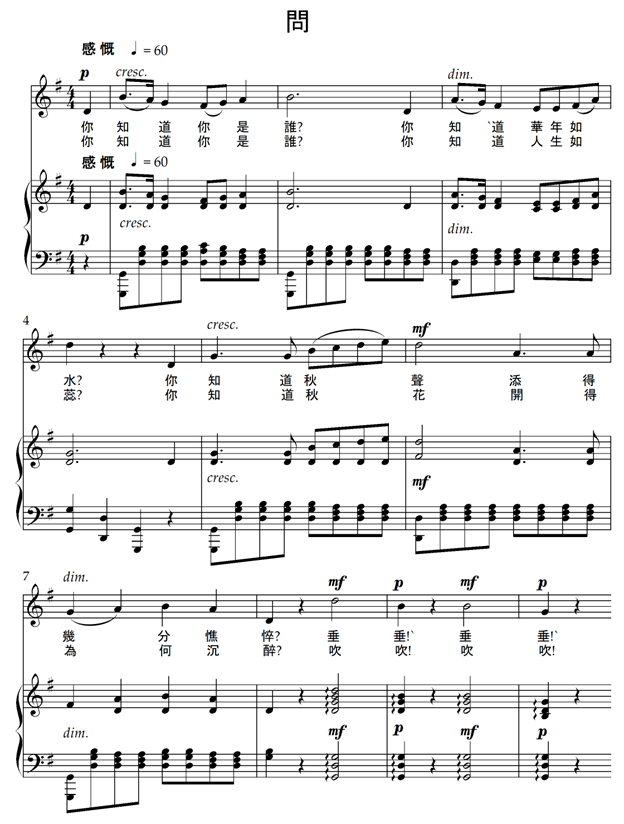

- Musical Settings (VII): “Questions” 問

- Musical Settings (VIII): “How Can I Help but Think of Her,” The Song

- Musical Settings (IX): “Listening to the Rain” 聽雨

- Musical Settings (X): “Bouquets in the Vase” 瓶花

- Musical Settings (XI): “Not a Flower” 花非花

- Musical Settings (XII)— “In the Mountains” 山中

- Musical Settings (XIII): “Chance Encounter” 偶然

- Musical Settings (XIV): Art Songs and Patriotism

Xiao Youmei was a prolific composer and writer. However, a century after the publication of his song collections, most of the works are rarely performed. “Wen” 問 [Questions]—No. 15 of Jinyue chuji—was one of the few exceptions.

__The lyric

你知道你是誰?

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 ni3 shi4 shui2 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄋㄧˇ ㄕˋ ㄕㄨㄟˊ]

Do you know who you are?

你知道華年如水?

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 hua2 nian2 ru2 shui3 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄏㄨㄚˊ ㄋㄧㄢˊㄖㄨˊ ㄕㄨㄟˇ]

Do you know the ravishing time of youth rushes away like water?

你知道秋聲, [ni3 zhi1 dao4 qiu1 sheng1 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄑㄧㄡˉ ㄕㄥˉ ]

添得幾分憔悴? [tian1 de5 ji3 fen1 qiao2 cui4 / ㄊㄧㄢˉ ㄉㄜ˙ㄐㄧˇ ㄈㄣˉ ㄑㄧㄠˊ ㄘㄨㄟˋ]

Do you hear the sounds of autumn

adding to the sense of distress?

垂垂! 垂垂![1] [chui2 chui2 chui2 chui2 / ㄔㄨㄟˊ ㄔㄨㄟˊ ㄔㄨㄟˊ ㄔㄨㄟˊ]

你知道今日的江山,

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 jin1 ri4 de5 jiang1 shan1 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄐㄧㄣˉ ㄖˋ ㄉㄜ˙ㄐㄧㄤˉ ㄕㄢˉ]

有多少淒惶的淚?

[you3 duo1 shao3 qi1 huang2 de5 lei4 / ㄧㄡˇ ㄉㄨㄛˉ ㄕㄠˇ ㄑㄧˉ ㄏㄨㄤˊ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄌㄟˋ]

Do you know how many forlorn tears there are

in the country today?

你想想呵! [2] [ni3 xiang3 xiang3 a5 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄚ˙]

Think about it!

對, 對, 對. [dui4 dui4 dui4 / ㄉㄨㄟˋ ㄉㄨㄟˋ ㄉㄨㄟˋ ㄉㄨㄟˋ]

********************

你知道你是誰?

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 ni3 shi4 shui2 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄋㄧˇ ㄕˋ ㄕㄨㄟˊ]

Do you know who you are?

你知道人生如蕊? [3]

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 ren2 sheng1 ru2 rui3 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄖㄣˊ ㄕㄥ ㄖㄨˊ ㄖㄨㄟˇ]

Do you know life is fragile like a flower bud?

你知道秋花, [ni3 zhi1 dao4 qiu1 hua1 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄑㄧㄡˉ ㄏㄨㄚˉ]

開得為何沉醉? [kai1 de5 wei4 he2 chen2 zui4 / ㄎㄞˉ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄨㄟˋ ㄏㄜˊ ㄔㄣˊ ㄗㄨㄟˋ]

Do you know why autumn flowers

bloom so euphorically?

吹吹! 吹吹! [chui1 chui1 chui1 chui1 / ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄔㄨㄟˉ]

你知道塵世的波瀾,

[ni3 zhi1 dao4 chen2 shi4 de5 bo1 lan2 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄓˉ ㄉㄠˋ ㄔㄣˊ ㄕˋ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄅㄛˉ ㄌㄢˊ]

有幾種溫良的類?

[you3 ji3 zhong3 wen1 liang2 de5 lei4 / ㄧㄡˇ ㄐㄧˇ ㄓㄨㄥˇ ㄨㄣ ㄌㄧㄤˊ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄌㄟˋ]

Do you know, amongst the worldly vicissitudes,

how many kind and gentle sorts there are?

你講講呵: [ni3 jiang3 jiang3 a5 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄐㄧㄤˇ ㄐㄧㄤˇ ㄚ˙]

Say it.

脆, 脆, 脆! [cui4 cui4 cui4 / ㄘㄨㄟˋ ㄘㄨㄟˋ ㄘㄨㄟˋ]

As a proponent of new-style lyrics, Xiao Youmei found that the fixed lengths in ancient verses, be it four-word, five-word, or seven-words, were too limiting to the rhythmic developments. As for poetry of the later periods, such as ci 詞 of the Song Dynasty and qu 曲 of the Yuan Dynasty, even though their verse lengths varied greatly, their vocabulary and contents were not suitable for modern society. Xiao also thought that traditional poems often narrowly reflected the personal feelings of the poet: Laments and regrets would easily lead to melancholy and despondence.[4]

Yi Weizhai’s text was of two parallel stanzas. Each stanza was further divided into two sections by a set of reiterative locutions. The lengths of verses ranged from three to fifteen words.[5] With a natural rhythmic flow, it was an ideal song text for Xiao.

With gentle words, the poet asked the readers to take a deeper look at the meaning of life. From the words “華年” (“flowering years”) and “蕊” (“flower bud”), we sensed that these verses were meant for young people whose lives were full of possibilities. Written soon after the May Fourth Movement led by student protestors, Yi clearly wished them to be aware of their responsibility to the country and continue the push for reform.

In 1907, after a failed uprising against the Qing Dynasty, the revolutionary heroin Qiu Jin 秋瑾 was captured and tortured. Refused to succumb to pressure, before her execution, in lieu of a confession, she famously wrote down the verse: “秋風秋雨愁煞人.” (“Autumn wind and autumn rain make one anguish excruciatingly.”), lamenting the fate of the nation.[6] Actively involved in the revolutionary movement himself, Yi must have been familiar with these verses. As he directed the reader to listen to the sounds of autumn, subtly he was forewarning the decline of the country.

He used the words “沉醉” (literally, “intoxicating”) to describe the blossoming autumn flowers. Corresponding to the phrases “華年如水” and “人生如蕊” in previous verses, he was cautioning the young readers to not indulging in fleeing joy.

Both Xiao and Yi believed that, for song verses, rhyming was a necessity but should not be restrictive. In his article “Gei zuo ge tongzhi yi feng gongkai xin” 給作歌同志一封公開信 [A Public Letter to Song-Writing Comrades], Xiao stressed that, instead of following the old rhyming practice, writers of new lyrics should use the recently standardized national pronunciation as guidance.[7] He attached a comprehensive rhyme table to the article.[8] All the rhyming words in “Wen” end on the [ei/ㄟ] sound:[9] 淚 and 類are with simple final; 誰, 水, 悴, 垂, 對, 蕊, 醉, 吹, 脆, compound final [ui/ㄨㄟ].

__Diction notes

- Contemporary performers often use the colloquial pronunciation [shei/ㄕㄟˊ] for the character 誰. The literary pronunciation [shui2/ㄕㄨㄟˊ], however, rhymes better with “水” [shui3/ㄕㄨㄟˇ] and “蕊” [rui3/ㄖㄨㄟˇ] in the following verses.

- To reflect the conversational nature of the text, neutral tone would be suitable for 的, 得, 呵.

- Consecutive third tones appear three times in the poem: “你想想” [ni3 xiang3 xiang3 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄒㄧㄤˇ], “有幾種” [you3 ji3 zhong3 / ㄧㄡˇ ㄐㄧˇ ㄓㄨㄥˇ], “你講講” [ni3 jiang3 jiang3 / ㄋㄧˇ ㄐㄧㄤˇ ㄐㄧㄤˇ]. Tone sandhi 3-2-3 should apply.

__Musical Contents

Xiao Youmei’s musical treatment of “Wen” is a simple sixteen-measure strophic structure in G major. The vocal line, ranged from D4 to E5, can be easily managed by most singers. The top voice of the piano accompaniment is in unison with the melodic line. Only primary chords are used in the harmonic progression. In the original edition, 感慨 (sighing emotionally) was given as the expression mark, followed by the metronomic marking of (♩ = 60).

Rhythmically, the song moves in steady eighth-note pulses through the first section of each stanza. After the reduplications “垂垂—垂垂” and “吹吹—吹吹,” sets of triplets heighten the emotional intensity in measures ten to thirteen. The music then ends in a contemplative mood.

__Conclusion

The simplicity of the music made it accessible to the public. Created at the time when the nation was going through dramatic changes, it was a spiritual awakening for a generation of young people. A century later, it still encourages the modern audiences and performers, through soul-searching, to continue the work of nation-building.

[1] The reiterative locutions “垂垂—垂垂,” “對—對—對,” “吹吹—吹吹,” and “脆, 脆, 脆” are merely phonetic reduplications.

[2] The character 呵 has multiple meanings and pronunciations. Here, it is used as an alternative form of 啊, functioning as a modal particle. The suitable pronunciation should be [a] in the fifth-neutral tone.

[3] 蕊 [rui3], flower bud.

[4] Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅 and Long Muxun 龍沐勛, “Geshe chengli xuanyan” 歌社成立宣言 [Song Society Founding Manifesto], Xiao Youmei quanji. di er juan, Yinyue zuo pin juan 蕭友梅全集. 第二卷, 音樂作品卷 [Complete Works of Xiao Youmei, Vol. 2, Musical Works] (Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press, Shanghai, 2007), 399-400.

[5] The longer verses of eleven- and fifteen-words are often divided into two phrases.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qiu_Jin

[7] Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅, “Gei zuo ge tongzhi yi feng gongkai xin” 給作歌同志一封公開信 [A Public Letter to Song-Writing Comrades], Xiao Youmei quanji. di yi juan, Wen luen zhuan zhu juan 蕭友梅全集. 第一卷, 文論專著卷 [Complete Works of Xiao Youmei, Vol. 1, Critical Essays] (Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press, Shanghai, 2007), 742-744.

[8] Ibid., 745-772.

[9] The Zhuyin symbols give a clearer indication of the rhyming sounds than the pinyin.