- Finding a voice: Chinese art songs

- Two rivers and a wall (I): The Yellow River 黃河

- Two rivers and a wall (II): The Yangtze River 長江

- Two rivers and a wall (III): The Great Wall 萬里長城

- All about Confucius

- Chinese Poetry (I): Classic of Poetry 詩經

- Chinese Poetry (II): More about “Guanju”

- Chinese Poetry (III): Songs of Chu 楚辭

- Chinese Poetry (IV): “Song of the Yue Boatman” 越人歌

- Chinese Poetry (V): Han and Jian’an

- Chinese Poetry (VI): Transition and transformation

- Chinese Poetry (VII): Tang poetry

- Chinese Poetry (VIII): Three Refrains of Yangguan 陽關三疊

- Chinese Poetry (IX): Ci—Lyric verses

- Chinese Poetry (X): The Great River Flows Eastwards 大江東去

- Chinese Poetry (XI): Autumn Sentiments 聲聲慢

- Chinese Poetry (XII): A Love Song 卜算子

- Chinese Poetry (XIII): Turning Point

- Chinese Poetry (XIV): Verses of Red Beans 紅豆詞

- Chinese Poetry (XV): Revolutions

- Chinese Poetry (XVI): How Can I Help but Think of Her? 教我如何不想她

- Chinese Poetry (XVII): Chance Encounter 偶然

- Musical Settings (I): Introduction

- Musical Settings (II): Words, Tones and Music

- Musical Settings (III): Diction

- Musical Settings (IV): “The Great River Flows Eastwards,” The Song

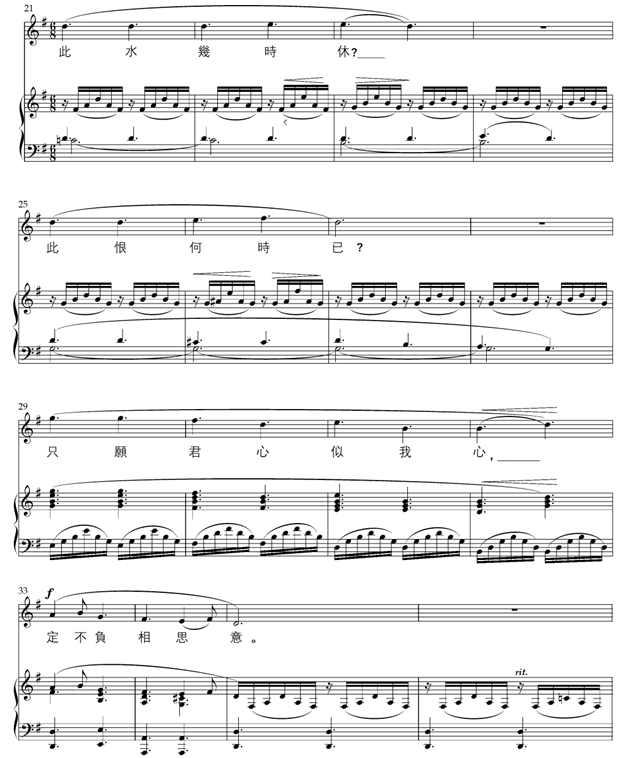

- Musical Settings (V): “I Live Near the Headwaters of the Long River,” The Song

- Musical Settings (VI): Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅 and Yi Weizhai 易韋齋

- Musical Settings (VII): “Questions” 問

- Musical Settings (VIII): “How Can I Help but Think of Her,” The Song

- Musical Settings (IX): “Listening to the Rain” 聽雨

- Musical Settings (X): “Bouquets in the Vase” 瓶花

- Musical Settings (XI): “Not a Flower” 花非花

- Musical Settings (XII)— “In the Mountains” 山中

- Musical Settings (XIII): “Chance Encounter” 偶然

In the 1920s, Qing Zhu’s contemporaries, namely Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅 and Zhao Yuanren 趙元任, began using modern poetry in their art songs. Qing Zhu himself also contributed to poetic writing with his collection Shi qin xiang le 詩琴響了, published in 1931.[1] Nonetheless, for his own musical compositions, he seemed favored traditional poetry.

His setting of “Wo zhu Chang Jiang tou 我住長江頭” (I live near the headwaters of the Long River) appeared in the second issue of Yue yi in July of 1930. The lyric, written by Li Zhiyi 李之儀, was another ci of the Northern Song Dynasty. Unlike “The Great River Flows Eastwards,” sophisticated and rooted in historical anecdotes, Li’s poem was folklike yet personal, in which the protagonist, separated from her love, expressed her nostalgic thoughts and professed her faith. [2]

Qing Zhu’s musical treatment fully reflected the characters of the poem.

—The river

The “Long River 長江” in the poem is more commonly known as Yangtze River 揚子江 to Westerners.[3] It is the same river that inspired Su Shi 蘇軾 to write his Niannujiao 念奴嬌.

For thousands of years, the Long River irritated farmlands, provided transportation, and, most importantly, connected Chinese souls. Less temperamental than its northern counterpart, the Yellow River, it was beloved by Chinese people—commoners and elites alike, and, therefore, had been a frequent subject in literary works.

In the poem, the length of the river, indicated by its name, caused the separation of the lovers. At the same time, its water connected them and nurtured their love.

–Lyrics

我住長江頭, 君住長江尾。

wo3 zhu4 chang2 jiang1 tou2, jun1 zhu4 chang2 jiang1 wei3.

ㄨㄛˇㄓㄨˋㄔㄤˊㄐㄧㄤ ㄊㄡˊ,ㄐㄩㄣ ㄓㄨˋㄔㄤˊㄐㄧㄤ ㄨㄟˇ

日日思君不見君,共飲長江水。

ri4 ri4 si1 jun1 bu2 jian4 jun1, gong4 yin3 chang2 jiang1 shui3.

ㄖˋㄖˋㄙ ㄐㄩㄣ ㄅㄨˊㄐㄧㄢˋㄐㄩㄣ, ㄍㄨㄥˋㄧㄣˇㄔㄤˊㄐㄧㄤ ㄕㄨㄟˇ

此水幾時休,此恨何時已。

ci2 shui3 ji3 shi2 xiu1, ci3 hen4 he2 shi2 yi4.

ㄘˊㄕㄨㄟˇㄐㄧˇㄕˊㄒㄧㄡ, ㄘˇ ㄏㄣˋㄏㄜˊㄕˊㄧˇ

只願君心似我心,定不負相思意。

zhi3 yuan4 jun1 xin1 si4 wo3 xin1, ding4 bu2 fu4 xiang1 si1 yi4.

ㄓˇㄩㄢˋㄐㄩㄣ ㄒㄧㄣ ㄙˋㄨㄛˇㄒㄧㄣ, ㄉㄧㄥˋㄅㄨˊㄈㄨˋㄒㄧㄤ ㄙ ㄧˋ

—Gender

The word jun 君 is a polite form of second-person singular male pronoun. Among couples, it carries a sense of respect and, at the same time, endearment. Hence, the poem was written from a female point of view.

Should the musical setting be sung only by female voices? For the following reasons, the answer should be no:

•The lyrics were written by a male poet, emulating a feminine voice.

•The subjects “love” and “faith” are universal and gender-neutral.

•A male singer can present the piece either as a third-person narrator, as a second person receiving the message of love, or in first person unburdened by the gender specification.

—The setting

The vocal lines of Qing Zhu’s setting are tuneful yet simple. The steady and unaltered rhythm seems to represent the stoic and faithfulness of the protagonist. The continuous arpeggiations in the piano part, like a Greek chorus, bring forward the perpetuity of flowing river and the longing. A subtle countermelody, mostly in the tenor voice, accompanies the vocal line throughout.

The structure of the song is also straightforward. After a brief introduction, the first part of the poem, verses one to four, is presented in four musical phrases:

The one-sharp key signature leads many interpreters to believe that these phrases are in G major. This view is erroneous for several reasons:

•The first two measures and its two repetitions are made up of D major and B minor. Both would not be logical choice to establish the tonality of G major.

•The first three phrases all end in E minor.

•There is an absence of any cadential movement into G major.

The initial phrases are, in fact, in E pentatonic minor. A pentatonic minor scale consists of scale degrees. first, flat third, fourth, fifth, flat seventh. The configuration of E pentatonic minor, therefore, is E-G-A-B-D.[4] In Chinese terms, it will be in 羽[yu3/ㄩˇ] 調式 (mode): 羽-宮 [gong1/ㄍㄨㄥ]-商 [shang1/ㄕㄤ]-角 [jué/ㄐㄩㄝˊ]-徵 [zhǐ/ㄓˇ]. The f-sharp, in theory, is a lowered second pitch in the scale—變宮 [bian4/ㄅㄧㄢˋ] (modified “gong”).

With this masterly choice of tonality, Qing Zhu was able to establish the folk-song quality of the section. He was also able to transition smoothly into an A major cadence in the fourth phrase, leading into the new tonal center G major for the following verses.

The first part of the poem is a description of the geographic separation as well as the emotional connections through the river between the lovers. The second part, on the other hand, is a personal reflection of the protagonist. She first laments and questions the impossibility of reunification. Then, she professes her faithfulness.

Verse five starts with a D-7 chord and quickly settles into G major. The tonality remains clear throughout the section and ends with an authentic cadence in D major—not yet a musical conclusion.

Dappled by diminished-seventh in measures thirty-eight and forty-two, the second statement of verses five and six are darker than the first one. The shadow was cast away quickly in the following confirmative phrases. This time, an added seventh—c-natural—pushes the music forward into the third and final statement of verses five to eight.

The final section, measure fifty-three to sixty-eight, is clear off any tonal ambiguity. With the higher tessitura of the vocal line, the dynamic level should be easily achievable. It will be the pianist’s job to keep everything under control till the final chord.

[1] Shi qin xiang le詩琴響了 was published by The Commercial Press 商務印書館 under Liao Shangguo’s pen name Li Qing 黎青.

[2] goldfishodyssey.com/chinese_poetry_xii_a_love_song_我住長江頭

[3] goldfishodyssey.com/two_rivers_and_a_wall_ii_the_yangtze_river_長江

[4] Pentatonic_scale#Minor_pentatonic_scale_Wiki