After setting “The Great River Flows Eastwards 大江東去” by Su Shi 蘇軾 to music in 1920, Qing Zhu 青主 focused on his political career and did not write any new works until the early 1930s. Meanwhile, as part of the cultural reform movement, other western-educated composers began creating songs with newly written lyrics. Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅 (1884-1940) and Yi Weizhai 易韋齋 (1874-1941) were pioneers of such works.

Xiao received his music education first in Japan (1901-1909) and later in Germany (1912-1919).[1] With a firm conviction of the power of music as a medium in character building, he devoted his time and effort in promoting music education after returning to China. While in Beijing, he founded and led the Music and Physical Education Department of Beijing Women’s Higher Normal College 北京女子高等師範學校 (1920), The Music Training and Research Institute affiliated to Beijing University 北京大學附屬音樂傳習所 (1922), and Music Department at Beijing National Arts College 北京國立藝術專門學校音樂系 (1926).[2] With the support of Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培, Xiao established the National Conservatory of Music 國立音樂專科學校—today’s Shanghai Conservatory of Music—in Shanghai in 1927.

Keenly aware of the need for teaching materials which were suitable for Chinese students in modern time, Xiao joined forces with lyricist Yi Weizhai to create songs, using Western harmony and newly written words. Jinyue chuji《今樂初集》 [First Collection of Todays Music] (1922) and Xinyue chuji 《新樂初集》 [First Collection of New Music] (1923) were the results of their collaboration.

___Yi Weizhai 易韋齋 (1874-1941)[3]

Born Yi Tingxi 易廷熹 on March 13, 1874, in Heshan, Guangdong 廣東鶴山, Yi received his early literary training at Guangya Academy 廣雅書院and was a disciple of phonologist Chen Li 陳澧.[4] After attending Aurora University 震旦書院[5] in Shanghai briefly, he went to Japan, studying languages and education.[6] A litterateur, Yi was also gifted in painting and calligraphy, and was especially known for his seal carving 篆刻.

Yi Weizhai and Xiao Youmei both studied in Japan during the first decade of the twentieth century and were active in revolutionary movements led by Sun Yat-sen.[7] After the Xinhai Revolution in 1912, they both held secretarial positions at the Presidential Office of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China in Nanking.[8] Their paths crossed again in the 1920s in Beijing where they were both teaching at various higher education institutions.[9]

Xiao was known for his uncompromising integrity and professionalism. Yi, on the other hand, despite his talents and knowledge, handled daily affairs and his career with a laissez-faire attitude. Their mutual interest in creating new style lyrics and songs brought them together.[10] Xian’s niece Xiao Shuxian 蕭淑嫻 recalled that, her uncle and Mr. Yi bought a small house in the western suburb near the Summer Palace 頤和園 as their pied-à-terre and studio. During summer months, each occupying one room, Yi wrote the lyrics and Xiao composed the songs and the piano accompaniments. Every time they completed two or three songs, they would bring the new works back to the city, asking friends and relatives to try them out.[11]

___Jinyue chuji《今樂初集》

Jinyue chuji, the first collection of the Xiao-Yi collaboration, was published by the Commercial Press in October 1922 and reprinted in November of the following year.[12] Among the twenty selections, three of them were for two-part chorus; three for three parts. The last four pieces were about women’s education and empowerment.

With the exception of a forward by Huang Jie 黃節[13], the entire volume, including the front-page art, music scores and texts, was hand-crafted by Yi Weizhai: the texts were in traditional calligraphy; the music in western staff notation. It was then produced using photographic printing process. On the one hand, it exposed the challenges that all the proponents of western music in China encountered during this period. On the other hand, it showcased the modernized printing technology which was instrumental in advancing new cultural development.

To fully appreciate the concept and the content of this collection, it is necessary to examine both the Preface and the Editorial Summary, both written by Yi in Classical Chinese:

Preface

I believe that our musical culture has never been declining more than the present day. Our forefathers educated people in three sets of disciplines— [six virtues, six principles of conduct, and six skills][14], music was one of the six skills. Ancient books were largely comprised of rhymed verses. It was understood back then that [musical] sounds were derived from one’s heart, without meaningless differentiation between social classes. In later times, cultivated music was monopolized by the ruling class. For the commoners, music was lessened to folk tunes. The literary creations of poets, henceforth, could not all be set to music. On the other hand, impertinent songs with plebeian texts proliferated and spread all over the country. The inundation causes one to feel nothing but sad and fatigue. I came to the north last year and reconnected with Mr. Xiao Youmei who invited me to write short lyrics. He then set them to music. The works were rather amicable. Therefore, we taught them to the students at the Beijing Women’s Higher Normal College. The effect was quite elegant and lovely. So, we continued the work and resulted in a number of pieces. Mr. Sun Zhong 孫壯[15]from Da Xing 大興noticed and appreciated them. Through his firm, the Commercial Press, he photo-engraved the works to share with teachers nationwide. I named this collection “The First,” as to carry on, and to gather comments for expansion and improvements. As I and Mr. Xiao each completed our editorial work, I, thus, encapsulated the essence of the collection.

___In the year of rénxū,[16] Yi Weizhai

弁言

吾以為樂之銷沈,未有甚於此時者也。前人以鄉三物 [六德、六行、六藝][17] 教民,樂為六藝之一。古書多有韵之文,其時知聲由心生,無上下貴賤妄生分别。後世樂私於君,下此者夷於謠諺,詩人文之,乃不能盡被弦管,而謠肆之聲、僿俚之辭,起而徧國中,横流第使人哀乏矣。余年前北來,重值蕭君友梅,約為短歌,君譜之聲。甚龤,乃以授北京女高師諸生,無甚婉渺,由是繼作,遂得如干首。大興孫君壯,見而善之,介其商務書館,得而影印,以餉海內教席。余謂此為初桄,賡此而起,又弥思增善也。今與蕭君各自寫㝎[18],略其概於此。

___壬戌 易韋齋

Editorial Summary

1. The majority of works in this collection are suitable for applications in middle schools and above. For higher primary schools, public schools, elementary schools, etc., there will be further editions to be published subsequently.

2. Lyrics and music in this collection are all newly composed. Old sources were referenced but not plagiarized.

3. In our country, graduates from secondary schools and junior normal colleges were often afraid of being singing teachers. And there were many of them who could not read music. This was because when they were in school, even though there were music courses, there were, unfortunately, no appropriate instructional materials. Hence their instructors frequently used English songs and texts. This was a big mistake. Students surely were not yet able to comprehend the meaning of the texts thoroughly and to pronounce the words accurately. Using such materials, how would it be possible to arouse their interest in singing[?] Mindful of such mistakes, the songs in this collection are written in Chinese only, so that students will not waste effort on language barriers, thus can be more focused and benefit more effectively.

4. Occasionally, idioms and historical references are used in the lyrics of this collection. Originally, we planned to provide annotation for each of them. Yet, since there were no obscure or incomprehensible references, and due to publication deadlines, this task, therefore, would wait until a later time.

5. Lyrics do not have to be restricted by rhymes but should never be without rhymes. Applications of rhymes in the texts of this collection were done with scrutiny and intense care. Those who recognize such efforts would certainly appreciate it.

6. Incorrect interpretation of the texts of songs will lead to misunderstanding. Hopefully, the public will interpret them correctly and critique them with a righteous attitude.

7. In music scores, to accommodate singers, words are dispersed and placed near the notes; thus, disrupting the structure and flow of sentences and verse, making it inconvenient to the literary aficionados. Therefore, the lyrics are gathered in a separate attachment at the end of the collection, ready to be examined by literary connoisseurs.

8. Fù [descriptive], bǐ [comparative], xing [derivative] were three of the six disciplines of classical poetry. Each song text in this collection is also based on these three approaches and carries subtle nuances. Metaphorical admonitions concealed in the verses are mostly gentle satires. Instructors and students both can obtain the messages by associating the words with current events.

9. Currently, the music in the song collections used in our schools are mostly based on foreign tunes. Since most lyricists are not familiar with musical applications, verses often do not match musical phrases. This is one of the major reasons that elementary and middle school students lack interest in singing courses. The music in this collection was composed based on the meaning of the verses. Naturally, there will be no conflicts between music and words.

10. Our traditional music always favored minor scales; therefore, the sound was often melancholy. If we wish to enhance our music, we must move to using major keys (major scales). Because their sounds are uplifting and exuberant, easily making one feel excited. Following this logic, this collection uses only major keys in the scoring. Except for #F and bG, the other eleven keys were all included in the music. This can also offer students opportunities to practice key identification and notation. As for music in minor keys, they will be used later in future collections.

11. The musical contents of this collection are, tentatively, organized by categories. When used in teaching, one should arrange the order, taking into account the students’ level. In general, songs with longer texts (such as “Tang Shan,” “Benyuan,” etc.) and songs in which the vocal lines do not match the accompaniments (such as “Years”) should be taught last. For students who are not able to identify keys, naturally, pieces in keys with fewer flats and/or sharps should be taught first; ones with more signs later. Before students are familiar with one key, it is not suitable to teach them a second key—to avoid confusion.

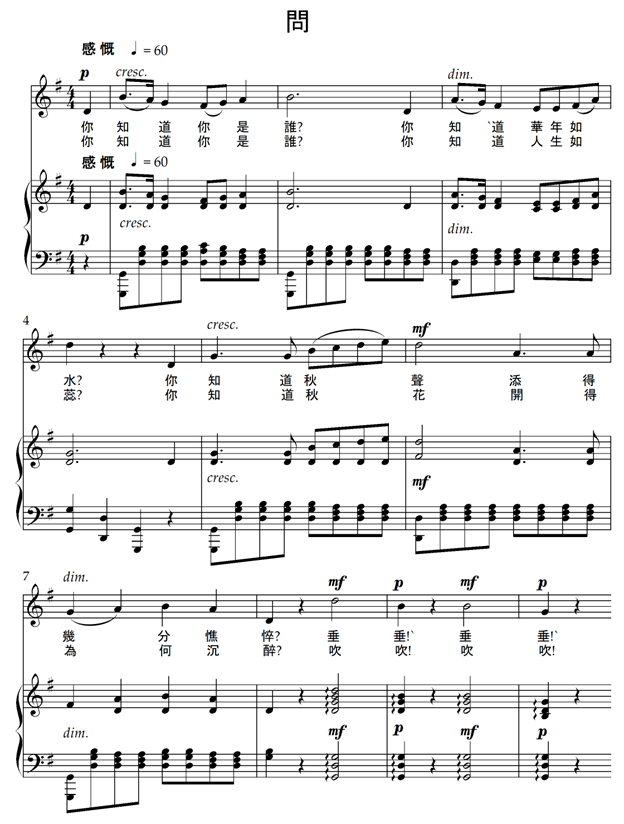

12. “Poetry is to convey one’s aspiration.” Therefore, when singing a piece, it is necessary to be able to express the meaning of the lyrics. On the upper left corner of each song in this collection, expression terms (such as “majestic,” “joyful”) are given. We hope that the instructors will pay special attention to these terms.

13. The performance tempos differ from song to song. In this collection, following the expression terms, a tempo range (such as ♩ = 60, ♩ = 80) is marked. Please be mindful of these markings.

14. Currently, [western-styled] music in our country is still in its infancy. Most singers do not like accidental half-steps (or modulations). This is due to a lack of practice. In order to ease into chromatic singing, modulation only occurs in the second section of “Tang Shan.” The other pieces are all sung in the original key throughout. Pieces with chromatic applications will gradually increase in later productions.

編輯大意

一. 此集大部分,是適用於中等以上學校[;] 高小、國民、蒙學、各校,以次編箸,相繼出版。

二. 此集歌、曲, 俱是創作,用古有之,襲舊則無。

三. 我國中學,及初級師範畢業,往往憚於為唱歌教授,並多有未諳看譜者。其故由於在校時,雖有此科,苦嘸適當教材。乃其教之者,恆授以英文歌詞,是大謬也。學者於歌意,固未滲透解,即發音亦未能準確,執此教材,如何能引起唱歌興味[?] 今編此集,鑑此謬誤,特純用國文成歌,冀學者不他鹜而收實益。

四. 本集歌詞中,間有成語、及古事。本擬一一注出,但尚無奧僻難解者,以出版時間關係,此事遂俟異日。

五. 歌不必執泥於韵,但萬不能無韵。本集歌詞,用韵極攷核斟酌,識者玩之。

六. 歌之詞句,若加曲解,必生誤會。幸世人以正確之眼光觀之,以端嚴之態度,批評之,繩糾之。

七. 譜中歌詞,取便唱者,依音注字,歌之形式遂亡。專玩歌詞者,頗感不便。因別附歌集一束於後,備嗜文辭者鑒焉。

八. 賦、比、興,為詩六藝之三。本集各歌,亦體此三藝,均有弦外之意。主文譎錬,所謂婉而諷者居多。教者學者,均可於其時其事二者加之領會,則得之矣。

九. 現在吾國學校,所用歌集,其曲譜多採自外國。苐填詞者,多非諳樂理之人,致詞句每於樂句,不能針對。此亦為吾國中小學生對於歌唱一科,興味缺乏之一大原因。本集曲譜,純是比按歌意,創作而成[。] 自無詞曲互舛之處。

十. 吾國固有樂曲,向來善用小音階,故其聲多萎靡不振。欲改良吾國音樂,非改用大調不可 (即大音階)。以其聲多發揚蹈厲,易令人興起也。本集即根據此理,純用大調製譜。除大 #F 大 bG 兩調外,餘十一調,均以之入譜。藉此又可以與學者以練習辯調記譜之機會。至於小音階曲譜,當於次集以後用之。

十一. 本集內容,暫依歌之種類為次序。教時[,] 當依學生之程度,斟酌先後。大約較長之歌詞,(如湯山、本願 等) 及歌曲與伴奏不同者,(如 [年] 之類) 均應最後教授。對於未能辯調之學生,自應先授調號較少之曲,調號多者均應緩授。至於學生未認熟甲調之先,不宜即授乙調,防混亂也。

十二. 詩以言志,故凡唱一曲,須能將歌中含意,發表出來。本集各歌之左端,均用表情術, (如雄壯、喜樂、之類) 標明於上。希望教者,特加注意。

十三. 各歌唱奏,速度不一。本集於表情術語之後,即記明速度標準 (如 ♩ = 60, ♩ = 80 等) 亦希望注意。

十四. 吾國音樂,現尚幼稚,歌者多不喜臨時唱半音 (或轉調)。此皆由於缺少練習之故。本集為逐漸輸入唱半音起見,只於 [湯山] 歌,第二段轉調。餘均用本調歌唱,俟續出再以次增加此項有半音之歌曲。

Having spent years in Japan, both Xiao and Yi would have been familiar with “school songs” 學堂樂歌 created by Zeng Zhimin 曾志忞 (1879-1929), Shen Xingong 沈心工 (1870-1947), and Li Shutong 李叔同 (1880-1942).[19] Although some of these educational songs were written by the musicians, most of them were adaptations of existing western or Japanese songs, fitted with Chinese words. While they both wished to make singing a crucial part of secondary school curriculum, they disagreed with borrowing foreign music and words. Hence, they created a collection of new school songs with western-styled music and new-style lyrics.

As a poet, Yi favored the works of Liu Yong 柳永 and Wu Wenying 吳文英—both representatives of the wanyue 婉約 [delicate and demure] style of the Song Dynasty. He was known to have followed the versification in their works, especially the tone patterns, strictly in his own poems. [20] The literary contents in Jinyue chuji, the front matter narrations and the lyrics, were clear indications that Yi was not able to shake off the traditional influences even when attempting to create new-style works. The song texts were caught between Classical verses and plain language, difficult to understand and awkward to sing.

Despite its initial success, Jinyue chuji quickly faded into history. The songs in the collection were mostly forgotten. Critics often blamed Yi’s lyrics for this outcome. Nonetheless, as the music in the collection was written to fit the words, the composer should be equally responsible for the results.

As Yi mentioned, western-style music was in its infancy when the collection was written. One could also relate to the need to introduce the theory and practice to the students step by step. Avoiding minor keys all together so that the music would be uplifting and moral-strengthening seemed to be an extreme approach. Staying in one key throughout each song would certainly limit the emotional transitions and development.

Xiao’s music writing was also problematic. While simple melodies without chromatic patterns were convenient for beginners, they were, in most cases, not very interesting. The melodic contour often did not reflect the linguistic tones; the key words in the verses did not match the rhythmic stresses. Perhaps because of Xiao’s contribution to music education in China, there had been scarcely any negative commentary on his composition. In recent years, critics such as Meng Wentao began wondering, based on the disconnection between the lyrics and the musical contents, whether some of the melodies in the Xiao-Yi collections were composed first, and the words were fitted later.[21]

Jinyue chuji was followed by Xinyue chuji 《新樂初集》 (1923), a twenty-five-song collection based on the same editorial format, and three volumes of teaching materials including sight-singing exercises, entitled Xinxuezhi changge jiaokeshu 《新學制唱歌教科書》 [Singing Textbooks for the New School System] (1924).[22] From today’s point of view, the Xiao-Yi collections lack artistic value. As historical testaments, they reflect the struggles of intellectuals, individually and collectively, in a country striving to move away from traditions and finding its footing in the modern world.

When Xiao Youmei established the National Conservatory of Music in Shanghai in 1927, Yi joined the faculty, teaching Chinese and poetry. Together, they influenced a new generation of composers and lyricists.

[1] With a dissertation entitled, “Eine geschichtliche Untersuchung über das chinesische Orchester bis zum 17. Jahrhundert (Historical Research on the Pre-Seventeenth Century Chinese Orchestra),” Xiao received his Ph.D. at Königliches Konservatorium der Musik zu Leipzig (now Hochschule für Musik und Theater “Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy” Leipzig) in 1916. He was the first Chinese student to obtain a doctoral degree abroad.

[2] In older references, “Peking” would be used instead of “Beijing.”

[3] In addition to Weizhai 韋齋, Yi had an unusually long list of art names and aliases including Xi 熹, Ru孺, Ziru 子孺, Daan 大厂 (大庵), Daan jushi 大庵居士. This poses a challenge in consolidating references in his life and achievements. The name Xi熹 appears often in references on his work as a painter, calligrapher and seal maker uses the name; for his literary works, Weizhai 韋齋 or Daan 大厂 (大庵).

[4] Guangdong_Guangya_High_School_Wiki,

Chen_Li_(scholar)_Wiki

[5] Aurora_University_(Shanghai)_Wiki

[6] The exact timeline of Yi’s educations was not clear. However, he would have been at Aurora University after 2003 and have completed his study in Japan by 1912 around the time of Xinhai Revolution.

[7] Xiao joined Tongmenghui 同盟會 and worked closely with Sun. Yi became a member of Nanshe 南社 [South(ern) Society], a literary society founded by members of Tongmenghui.

Tongmenghui_Wiki

South_Society_Wiki

[8] Provisional_Government_of_the_Republic_of_China_(1912)_Wiki

[9] Yi taught at [Beijing] Higher Normal College 北平高等師範 and The Music Training and Research Institute.

[10] Long Muxun 龍沐勛, a younger contemporary and colleague of Xiao and Yi, gave vivid accounts of their lives and works in his articles, Yuetan Huaijolu 樂壇懷舊錄 [Nostalgia of Music World]. Qiushi Monthly 求是月刊, vol. 1, no. 2 (1944): 16-19 and Yuetan Huaijolu 樂壇懷舊錄續 [Nostalgia of Music World Continued]. Qiushi Monthly 求是月刊, vol. 1, no. 4 (1944): 18-25.

[11] Xiao Shuxian 蕭淑嫻, “Hueiyi wode shufu Xiao Youmei: Xiao Youmei de jiating han tade yoxue shenghuo” 回憶我的叔父蕭友梅:蕭友梅的家庭和他的遊學生活 [Remembering My Uncle Xiao Youmei: Xiao Youmei’s Family and His Academic Life], Wenhua shiliao cóngkang 文化史料叢刊, vol. 5 (1983): 32.

[12] Since its founding in 1897, the Commercial Press 商務印書館, has grown into one of the most influential private enterprises in both industrial and cultural advancements.

The_Commercial_Press_Wiki

http://www.cgan.net/book/books/print/g-history/big5_12/14_1.htm 中華印刷通史, 近代篇

[13] https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-hant/黃節

[14] The three disciplines were not listed in Yi’s original text. The three sets of disciplines were explained in Zhou li, Diguan Situ [The Rites of Zhou, Offices of Earth]. 周禮/地官司徒: 以鄉三物教萬民而賓興之:一曰六德,知、仁、聖、義、忠、和;二曰六行,孝、友、睦、姻、任、恤;三曰六藝,禮、樂、射、御、書、數。

[15] Sun Zhong 孫壯 (1879-1943), courtesy name Boheng 伯恆, was, at the time, the manager of the Beijing branch of the Commercial Press.

[16] The year of 1922, Sexagenary_cycle_Wiki. 1922 was an important year of National Education Reform. A new school system, known as Renxu School System, was implemented to extend the years of schooling—six years of primary school; three, lower secondary and three, upper secondary, and to strengthen vocational and science education.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6-3_school_system

https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/壬戌學制

[17] See note 13.

[18] 㝎=定

[19] The Call of Modernity: Chinese School Songs in the Early Twentieth Century, by ZhiZhi Li.

[20] Long, Yuetan Huaijolu, 21-22.

Liu_Yong_(Song_dynasty)_Wiki

https://cuhk.edu.hk/rct/renditions/authors/wuwy.html

goldfishodyssey_chinese-poetry-ix-ci-lyric-verses

[21] Meng Wentao 孟文濤, Zhongguo jinxiandai gequ chuangzuoshi zhong yige teshu jinjian shili—Shiyi Xiao Youmei yu Yi Weizhai hexie gequzhong de ciqu jiehe wenti 中國近現代歌曲創作史中一個特殊僅見事例 [My Opinion About Xiao Youmei’s Art Song], Huangzhong, Journal of Wuhan Conservatory of Music 黃鍾, 武漢音樂學院學報, 2005 (2): 26- 30. The English title, not a direct translation of the Chinese one, was used in the English abstract.

[22] Xinyue chuji 《新樂初集》 was reprinted in October 1925. An edition with new print setting and a few changed in the front matters was brought forward in 1934. The “New School System” specification in Xinxuezhi changge jiaokeshu 《新學制唱歌教科書》 would have been the “Renxu System,” implemented in 1922. See note 15.