__Bouquets in the Vase 瓶花[1]

南宋,范成大

Southern Song, Fan Chengda

《春來風雨無一日好晴因賦瓶花二絕》,其一:

“With springtime, came the wind and the rain. There hasn’t been one bright sunny day. Thus, I drafted two jueju poems on ‘bouquets in the vase’”—Here is one of the two:

滿插瓶花罷出遊,

Abandoning outdoor excursions,

I filled up the vase with bouquets of flowers instead.

[man3 cha1 ping2 hua1 man4 chu1 you2]

ㄇㄢˇ ㄔㄚˉ ㄆㄧㄥˊ ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄇㄢˋ ㄔㄨˉ ㄧㄡˊ

莫將攀折為花愁。

Do not pity the flowers for being snapped from the branches.

[mo4 jiang1 pan1 zhe2 wei4 hua1 chou2]

ㄇㄛˋ ㄐㄧㄤˉ ㄆㄢˉ ㄓㄜˊ ㄨㄟˋ ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄔㄡˊ

不知燭照香熏看,

Wouldn’t you know:

being appreciated under the candlelight, surrounded by aromatic incense,

[bu4 zhi1 zhu2 zhoa4 xiang1 xun1 kan4]

ㄅㄨˋ ㄓˉ ㄓㄨˊ ㄓㄠˋ ㄒㄧㄤˉ ㄒㄩㄣˉ ㄎㄢˋ

何似風吹雨打休?

Is incomparable to being beaten and destroyed by winds and rain.

[he2 si4 feng1 chuei1 yu3 da3 xiu1]

ㄏㄜˊ ㄙˋ ㄈㄥˉ ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄩˇ ㄉㄚˇ ㄒㄧㄡˉ

****************************

胡適,「瓶花詩」:

Hu Shi, “Poem on Bouquets in the Vase”

不是怕風吹雨打,

Not worried about flowers being beaten by winds and rain,

[bu2 shi4 pa4 feng1 chuei1 yu3 da3]

ㄅㄨˊ ㄕˋ ㄆㄚˋ ㄈㄥˉ ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄩˇ ㄉㄚˇ

不是羨[慕那]燭照香熏。

Not envy candlelight and fragrant incense. . .

[bu2 shi4 xian4 mu4 na4 zhu2 zhoa4 xiang1 xun1]

ㄅㄨˊ ㄕˋ ㄒㄧㄢˋ ㄇㄨˋ ㄋㄚˋ ㄓㄨˊ ㄓㄠˋ ㄒㄧㄤˉ ㄒㄩㄣˉ

只喜歡那折花的人,

Simply love the person who picked the flowers,

[zhi3 xi3 huan1 na4 zhe2 hua1 de5 ren2]

ㄓˇ ㄒㄧˇ ㄏㄨㄢˉ ㄋㄚˋ ㄓㄜˊ ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄖㄣˊ

高興和伊親近。

Pleased to be near her.

[gao1 xing4 he2 yi1 qin1 jin4]

ㄍㄠˉ ㄒㄧㄥˋ ㄏㄜˊ ㄧˉ ㄑㄧㄣˉ ㄐㄧㄣˋ

*****

花瓣兒紛紛謝了,

Petals are withering one by one.

[hua1 bɚ4 fen1 fen1 xie4 le5]

ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄅㄚˋㄦ˙ ㄈㄣˉ ㄈㄣˉ ㄒㄧㄝˋ ㄌㄜ˙

勞伊親手收存,

Troubling her to gather and preserve them,

[lao2 yi1 qin1 shou3 shou1 cun2]

ㄌㄠˊ ㄧˉ ㄑㄧㄣˉ ㄕㄡˇ ㄕㄡˉ ㄘㄨㄣˊ

寄與伊心上的人,

Sending them to the person in her heart,

[ji4 yu3 yi1 xin1 shang4 de5 ren2]

ㄐㄧˋ ㄩˇ ㄧˉ ㄒㄧㄣˉ ㄕㄤˋ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄖㄣˊ

當一封沒有字的書信。

As a letter without words.

[dang1 yi4 feng1 mei2 you3 zi4 de5 shu1 xin4]

ㄉㄤˉ ㄧˋ ㄈㄥˉ ㄇㄟˊ ㄧㄡˇ ㄗˋ ㄉㄜ˙ ㄕㄨˉ ㄒㄧㄣˋ

__Fan Chengda 范成大

Fan Chengda 范成大 (1126–1193), courtesy name Zhineng 致能,[2] was a statesman, author, and poet of the Southern Song Dynasty. His father Fan Yu 范雩 was a scholar and administrator. His mother was the granddaughter of the great calligrapher Cai Xiang 蔡襄. As a teenager, he lost both of his parents. This might have delayed his pursuit of a career in government.[3] In 1154, he passed the Jinshi 進士degree of the Imperial Examination and began a long and illustrious administrative career.

In June 1170, Emperor Xiaozong 孝宗 named Fan Chengda the special envoy to the Jin court, with the mission of regaining access to the Imperial Mausoleum of the Northern Song[4] and to renegotiate the ceremonial details of diplomatic exchanges.[5] Since the latter could easily be seen as a willful disregard of previous treaties and a provocation for war, the emperor refused to include it the official communication. Fan, fully aware of the challenges and dangers, accepted the daunting mission.

He chronicled his journey to the Jin capital in Lanpei lu 攬轡錄.[6] Starting on the day when he crossed the Huai River and ending on the day he reentered the Song territory, he described the existing conditions of historical sites, lives of commoners, and local customs. Along with Lanpei lu, Fan also wrote seventy-two seven-character jueju, further detailing the sceneries and his encounters with people. These poems were included in Fan’s poetic collection Shihu ji 石湖集.[7] The vivid language in both the prose document and the poems reflected the nostalgia and patriotism of the author towards his nation as well as his compassion for the Han people living under the Jurchen dynasty.

As his administrative duties took him to various regions, he continued the practice of annotating his experiences. In 1171, for his assignment as the magistrate of Jingjian prefecture 靜江府, Fan travelled from Wujun 吳郡 (Suzhou) to Guangxi/Guilin. He kept a travelogue, Canluan lu 驂鸞錄, from the seventh day of the twelfth lunar month in 1171 to the tenth day of the third month of the following year.[8]

Historically, southwestern regions were considered undesirable habitats because of the heat, the humidity, and the geographical challenges. Nonetheless, Fan seemed to have enjoyed his sojourn in the area. Shihu ji, Chapter 14 contained his poetic works of this period.[9] In 1175, during his long river journey to his new assignment in Sichuan, he penned Gui Hai Yu Heng Zhi 桂海虞衡志, a treatise on the topography and customs of Guangxi and Guilin.[10]

Rounding up his achievements and contributions as a writer of travel literature and documentarian were two more treatise: Wuchuan lu吳船錄 and Wujun zhi 吳郡志.[11] The former recorded his boat trip from Sichuan to Lin’an 臨安 in 1177. [12] The latter, written during Fan’s retirement, was a large-scale work of fifty chapters, encompassing the geography, history, luminaries, economy, and customs of Suzhou.

In autumn of 1183, after repeated pleadings, Fan was granted an honorary position and retired to his country home on the north shore of Shi Hu (石湖, Stone Lake).[13] His poetic works of this period reflected the joy of rustic lifestyle. The most representative among them are sixty vignettes on the idyllic scenes of four seasons– “Siji tianyuan zaxing” 《四季田園雜興》. Written in 1186, the collection comprised of five sets of seven-character jueju. Each set of twelve poems depicted the village life and sceneries of a different season: early spring, late spring, summer, autumn, and winter.[14]

Fan was often praised for his naturalistic approach by critics of the later periods and was recognized as one of the “Four Masters of the Southern Song Dynasty,” along with Yang Wanli 楊萬里, Lu You 陸游, and You Mao 尤袤. During the last years of his life, Fan Chengda compiled and edited his works and with the help of his son Fan Xin 范莘. In 1203 (嘉泰三年), ten years after his death, the entire body of his works was printed by Fan Xin and his brother Fan Zi 范茲. Entitled Shihu ji 石湖集, the compilation comprised of over hundred and thirty chapters. The poetic works, including ci 詞, fu 賦, yuefu 樂府, and old-style verses 古詩, and totaling over two thousand individual verses in 34 Chapters, are still in circulation.[15]

__ “Bouquets in the Vase 瓶花”

The two seven-character jueju appeared in Chapter 26 of Shihu Shiji.[16] Fan Chengda mentioned the year binwu 丙午 (1186) several times in the chapter. Since he organized his works in chronological order, these verses were likely written in that year.

Fan was turning sixty-one and not in good health.[17] The seemingly endless spring rains prevented the ailing poet from stepping outside. He filled up the vases with cut flowers, most likely his favorite meihua 梅花 (blossoms of Chinese plums),[18] bringing the outdoor beauty inside. Under candlelight, surrounded by the fragrance of incense, he reflected on the fragility of the flowers. Rather than allowing the inclement weather to cut short their existence, wouldn’t it be better for them to be admired?

__ “Poem on Bouquets in the Vase 瓶花詩”

In the preface to his first poetic collection Chang shi ji 嘗試集 (1920), Hu Shi 胡適 testified that he was already writing prose essays in plain language as early as 1906 (丙午).[19] His early poems were mostly in the traditional style. While studying at Cornell and Columbia, influenced by western literature, he began experimenting with vernacular poetry, despite the oppositions of his friends and colleagues.

Around the time he drafted “A Preliminary Discussion of Literature Reform” 《文學改良芻議》 (1916),[20] Hu started compiling his poetry. As a refutation to Lu You’s statement “Since ancient times, experiments never succeeded 嘗試成功自古無,”[21] Hu named his collection “Chang shi 嘗試” (“Experiments), with the goal of achieving success through experiments. Initially, he struggled with breaking through the constraints of versification. Gradually, he allowed the natural flow of the vernacular language to shape the verses.

“Poem on Bouquets in the Vase” was written on June 6, 1925, revised in 1928, and included in a later collection Chang shi hou ji 嘗試後集.[22] Zhao Yuanren called it “Commentary [on Fan Chengda’s Poem] by Hu Shi.”[23] While the first two verses, derivations of Fan’s poems, bore resemblance of traditional poetry, the remaining verses were in plain language.

The poet gathered the flowers not to protect them from the stormy weather, nor to enjoy them in solitude. He simply wanted to be near the person who cut the flowers. The word伊 yi in the later verses left little doubt that the poet was referring to a lady.[24] And, by the time the petals started falling, he might not be near her. It was his hope that she would collect and deliver the withering flowers as a message without words.

In his correspondence to Hu Shi dated July 3, 1925, Liang Qichao 梁啟超 gave high praise to this poem as well as another one from August of the previous year: “These two poems are exquisite and can be seen as ‘free-styled’ ci.”[25] By categorizing them as “ci,” Liang seemed to acknowledge their applicability as song lyrics.

Liang, a leading figure of the culture reform movement, not only supported the creation of new poetry but also cared very much about the qualities of these works. Rhyming was among his concerns. In Hu’s poem, the third and the fourth verses of both stanzas ended with same words—人 ren2 and 信 xin4. In Mandarin, they share the same final [n] with the ending words of the second verses 熏 xun1 and 存 zun2. 人 ren2, 熏 xun1, and 存 zun2 are level-tone words while 信 xin4 is oblique. Liang gave an interesting suggestion: “The work responding to the Shihu poem would be even more marvelous if the first and the third verses rhyme—the first one, oblique; the third, level. . ..” He did not clarify whether it should apply to both stanzas. This suggestion was unusual in several aspects: Traditionally, the rhyming of the initial verse was optional. The third verse should be unrhymed and with an oblique ending. Conceivably, Liang was embracing the experimental spirit fully and wished to break away further from the tradition.

__ “Ping Hua 瓶花” (1927)

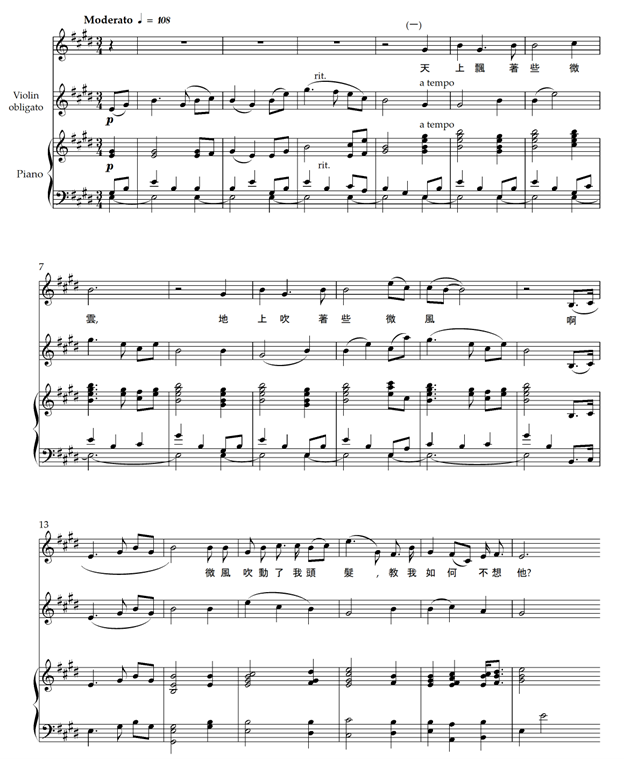

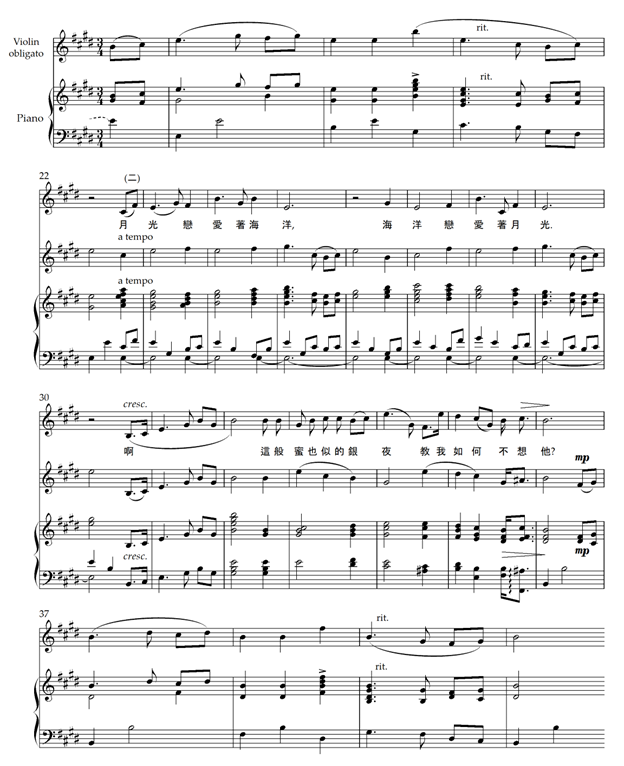

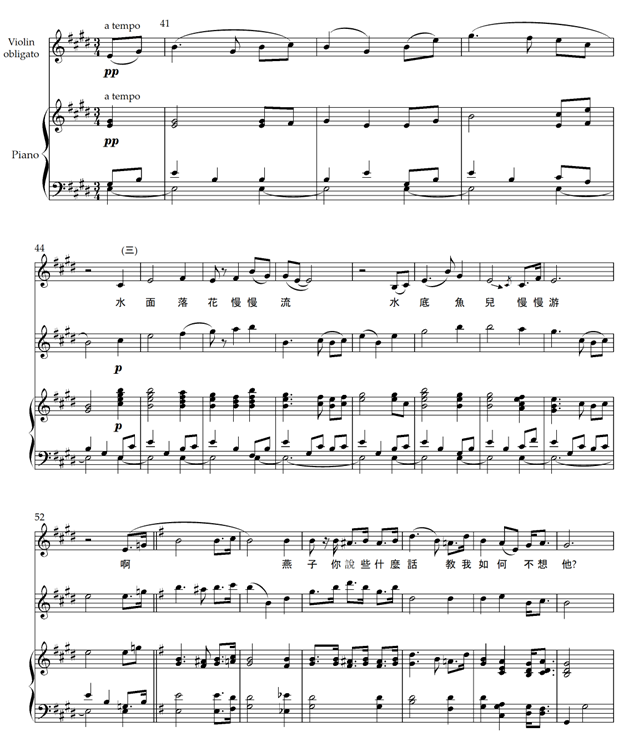

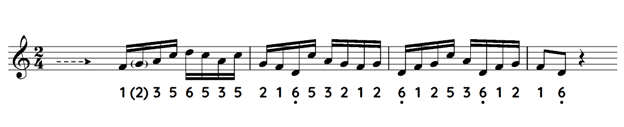

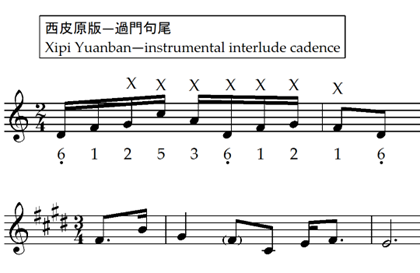

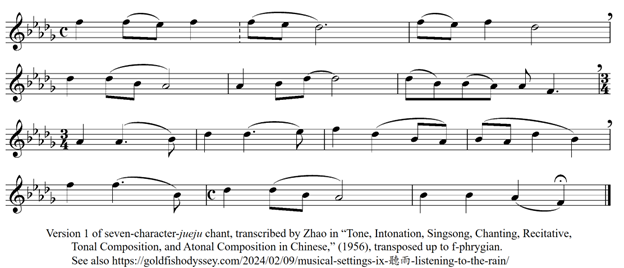

Reflecting the stylistic natures of the two poems, Zhao Yuanren divided his setting into two parts with distinct approaches. For the first part, set to the words of Fan Chengda, he turned to the poetic chanting tradition again, using the seven-character-jueju tune as the cantus firmus.

Using d-flat as the tonal center, the vocal lines were built on pentatonic scales and the accompaniment, seven-tone scales. Zhao avoided western-sounding harmonic progressions. In the Preface to Xinshi geji, he mentioned a few possibilities in creating Chinese-sounding harmonies, including using parallel fifth, which “Debussy had also experimented. . ..”[26] On the other hand, he rejected the idea that parallel fourth and fifth were the only options.[27] In “Ping Hua,” he relied heavily on various inversions of d-flat chords to provide harmonic movements. Chords based on e-flat and b-flat, ii and iv of D-flat major respectively, while added colors occasionally, were functionally obscure. The first dominant-tonic cadence took place at the end of verse four in mm. 23-24. The piano part, which had remained in high registers up to this point also became lower. The interlude ended with another full cadence in mm. 30-31 confirming the D-flat major tonality.

The composer noted that the application of falsetto would not only be suitable for the high vocal tessitura in this section but also enhance the “Chinese character.” This seemed to also indicate that this song should be sung by a male voice. The portamenti on the words 看 kan4 and 似 si4 in mm. 20 and 21 are mandatory.[28]

Verses one and two of Hu’s poem were set in C-sharp minor, the enharmonic (parallel) minor of the initial key. Subtly, the composer acknowledged the connection between the poems and the sense of denial in Hu’s words—however slightly. A Picardi third in mm. 40-41 brought back the original key. In the following two verses, the mood turned brighter as the music moved toward the dominant A-flat major. The large leaps in the vocal line highlighted the words “喜歡 xi3huan1” (like) and “高興 gau1xing4” (pleased). The words “人 ren2” (person) and “伊 yi1” (her) are set on the highest notes in the section.

Stealthily, the tonality took another turn to the subdominant G-flat major in mm. 51-58 as the piano moved steadily in eighth-note chords, depicting the petals falling gradually with the passing of time. The intimate final verses—寄與伊心上的人, 當一封沒有字的書信—were carried out in pentatonic vocal lines as in the opening section. The piano postlude echoed the opening introduction, wrapping up the song with longing and nostalgia.

A few textual modifications took place in the second part of the song: The words 慕 mu4 and 那 na4 were added to the verse 不是羨燭照香熏 to better the musical flow. The first verse of the second stanza appeared in a calligraphy in Hu’s own hand as 花瓣兒紛紛落了.[29] In Zhao’s setting and Chang shi hou ji, 落 luo4 (falling) was replaced by 謝 xie4 (withering).[30] A structural particle 的 de5 was added for the smoothness of the verse. In the musical setting, Zhao seemed to suggest that the rhotacization (erhua 兒化)in 花 [瓣兒] would be optional. This feature, if applied, would replace the [n] in 瓣 ban4 with a soft [ɹ] and could lead to a much gentler expression.

The composer proposed an optional ending for the piece: Return to the opening phrase for the final word 信 xin4. Use a vocal hum on a nasalized schwa [ә̃] in the next three phrases. The piano would conclude at the fine.[31] To execute this option, it would be necessary for the singer to breathe after 字 zi4 in m. 66. Humming on a nasalized schwa in the high register might be a challenge. For Chinese speaking singers [ㄤ/ang] might be a good option. A neutral humming sound similar to that in the “Humming chorus” in Madama Butterfly could also be effective.

Both the singer and the pianist need to be sensitive to the stylistic details throughout the entire song. In the opening section, the vocal line requires plenty flexibility to achieve the chant-like fluidity. The arpeggiated chords in the accompaniment should emulate the sounds of 琴 qin or 箏 zheng, articulated yet resonant. In m. 17, all sounds drop out except two simple notes in the piano, repeating and reflecting the word 愁 chou2 (sorrow). It is possible to lengthen the a-flat trill slightly. Nevertheless, the second note f should be in time, leading the singer into the following measure/verse smoothly. The pianist and the singer should coordinate carefully in m. 21 so the end of the portamento down to b-flat and the triplet upbeat in the piano part could blend well together. Again, the pickup notes should bridge the two phrases without delay or interruption.

In the first part of the Andantino section, at the end of each phrase, a brief melodic “insert” takes place in the higher register of the piano part. Three of these inserts are doubled in octave. Zhao indicated in the original score that they should be played with both hands—each handling one octave, clearly to keep the melodic pattern smooth and legato. Reminiscences of the chant, they should be delivered sans rigueur.

__Conclusion

The selections in Xinshi geji were roughly in chronological order. The opening numbers were two short settings of Hu Shi’s words: “他 He” and “小詩 Little Poem,” both written in 1922. Zhao Yuanren later thought that these works were “totally western (generic)” that foreigners would not be able to tell the nationality of the composer.[32] As he continued his efforts to intergrade western and Chinese features in his compositions, the last two solo pieces “聽雨 Listening to the Rain” and “瓶花 Bouquets in the Vase” were both built on traditional poetic chants.[33]

“Ping Hua” was not as popular as two 1926 songs, “Shang Shan 上山” (Climbing up the Mountain) and “Ye Shi Wei Yun 也是微雲” (Again the Thin Clouds). [34] The intricacies which make it special also post challenges to the performers. Nonetheless, its historical and artistic values cannot be ignored.

[1] In the revised edition of Xinshi geji 新詩歌集 (Taipei City, Commercial Press, 1960), an English title “flowers in the Jar” was given. The word “jar” projects a casual image which does not seem fitting to the elegance of the poem. Thus, a modified title is used here.

[2] Often appeared as 至能.

[3] In a lengthy epitaph for Fan Chengda, Zhou Bida 周必大 noted that Fan’s mother passed away when he was fourteen years old, and his father died in the following year. For a long period of time after that, Fan was not interested in advancing his career.

<資政殿大學士贈銀青光祿大夫范公神道碑, 慶元元年 (1195)>, 周必大. 文忠集, 卷61, 四庫全書, 集部四: . . . 考雩終左奉議郎秘書郎贈少師, 母秦國夫人蔡氏, 莆陽忠惠公之孫, 而潞忠烈公外孫也, 公在懐抱已識屛間字. 少師力教之, 年十二徧讀經史, 十四能文詞. 是嵗秦國薨; 明年少師薨. 公㷀然哀慕, 十年不出. 竭力嫁二妹, 無科舉意.

Chronologist Yu Beishan 于北山 (1917-1987) pointed out that Fan Yu retired from his official duty in 1143 and likely died later that year when Fan Chengda was eighteen years old.

Yu, Fan Chengda nianpu 范成大年谱 [A Chronicle of Fan Chengda’s life], Shanghai gu ji chu ban she 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai, 1987), 18.

[4] The Northern Song Imperial Mausoleum is in Gongyi 鞏義, near Zhengzhou City 鄭州市 in Henan Province. northern-song-dynasty-mausoleum-80755-www.trip.com/a>

[5] 宋史, 卷34, 孝宗本紀: “乾道六年, 閏[五]月 . . . 戊子, 遣范成大等使金求陵寢地, 且請更定受書禮

宋史紀事本末, 卷77, 隆興和議: “乾道. . . 六年閏五月, 以起居郎范成大爲金國祈請使, 求陵寢地及更定受書禮, 蓋泛使也.初, 紹興要盟之日, 金先約毋得擅易大臣, 秦檜益思媚金, 禮文多可議者, 而受書之儀特甚. 凡金使者至, 捧書升殿, 北面立榻前跪進, 帝降榻受書, 以授內侍. 金主初立, 使者至, 陳康伯令伴使取書以進. 及湯思退當國, 復循紹興故事. 帝常悔恨, 每欲遣泛使直之, 陳俊卿既屢諫不聽, 罷去. 至是, 乃令成大使金。

After the Jingkang incident (1127), the Northern Song Dynasty collapsed. The Jin Dynasty established by Jurchen leaders controlled the north and the Song court moved to Jinling 金陵, today’s Nanjing. Jingkang_incident_Wiki

As the power struggles continued between the Han and the Jurchen courts in the following decades, a few treaties and peace agreements were negotiated and ratified. In 1142, Emperor Gaozong 高宗 accepted the terms in the Treaty of Shaoxing 紹興和議. Among other things, the Song court formally relinquished control of territories north of the Huai River. It also acknowledged that it was a vassal state of the Jin court. The latter established the Jurchen dynasty as the ruler of a new tributary system, overturning the protocol in which, for centuries, centering around the Han courts.

In 1164—the second year of Longxing period 隆興二年, Emperor Xiaozong renegotiated new terms with the Jin court. In an official communication in early 1165, Xiaozong addressed himself as the nephew of the Jin emperor instead of a subordinate. Nevertheless, when receiving envoys from the Jin court, the Song Emperor must descend from his throne. It was his wish to reestablish a more balanced protocol. Treaty_of_Shaoxing_Wiki

[6] 攬轡錄_zh.wikisource.org 攬轡 means “holding the reins.”

[7] Shihu ji 石湖集, 卷 12. 石湖詩集_(四庫全書本)_zh.wikisource.org

Fan Shihu ji 范石湖集, ed. Fu Guisun 富貴蓀 (Shanghai, Shanghai guji chubanshe上海古籍出版社, 2006), 145-158.

[8] 驂鸞錄_(四庫全書本)_zh.wikisource.org

Luan鸞 is a Chinese mythological bird. Luan_(mythology)_Wiki

Canluan 驂鸞, literally “riding on the luan bird,” implies a divine journey.

There was a leap/intercalary month between the first and the second months in the lunar calendar that year. So, the entire journey lasted for about four months.

[9] goldfishodyssey.com/two-rivers-and-a-wall-ii-the-yangtze-river-長江

石湖詩集_(四庫全書本)/卷14_zh.wikisource.org.

[10] 桂海虞衡志, 四庫全書, 史部十一_zh.wikisource.org

In the final entry of Canluan lu, Fan commentated on its origin and suggested that readers who were interested in the customs of the region should turn to Gui Hai Yu Heng Lu. Since the latter was written several years later, it was believed that the entry might have been an addendum.

[11] 吳船錄_zh.wikisource.org

吳郡志_zh.wikisource.org

[12] Lin’an 臨安, capital city of the Southern Song Dynasty, is today’s Hangzhou 杭州.

Fan Chengda suffered from poor health throughout his life and often mentioned his ailments in his writings. In early 1177, he was severely ill. His seven-character lüshi, dated twenty-seventh day of the second lunar month, was annotated: “Just able to lift my head after illness 病後始能扶頭.” In Wuchuan lu, Part I, he mentioned that he nearly died of sickness in the spring: “今春病少城,幾殆,僅得更生. . ..” As he recovered, he requested for resignation and returning to the east.

[13] Fan was afflicted by prolonged symptoms of dizziness. He wished to retire from the court. On his fifth appeal, Xiaozong Emperor granted him the position of Zizheng Daxueshi 資政大學士 as an honorary political counsel, and a ceremonial appointment administering Dongxiao temple洞霄宮.

[14] 石湖詩集 (四庫全書) /卷27_zh.wikisource.org

[15] According to Zhou Bida’s epigraph and Song Shi, <Yi Wen Zhi> 宋史, 藝文志, the collection contains 136 chapters. Yu Beishan 于北山 noted in Fan Chengda Nianpu 范成大年譜 that the complete collection was still in existence in Ming Dynasty but was largely dispersed and destroyed in later periods. Ibid., Preface, 4.

石湖詩集 (四庫全書)_zh.wikisource.org

诗文索引 宋 范成大 https://sou-yun.cn/

[16] There are also two five-character jueju of the same title in Chapter 32 of Shihu shiji.

[17] Binwu_Fire_Horse_Wiki

Upon the arrival of the new year binwu, Fan wrote a poem as a gift to himself for turning sixty-one and having completed a sexagenary cycle: “丙午新年六十一嵗俗謂之元命作詩自貺.” Traditionally, Chinese babies are one year old the year they are born.

He also mentioned convalescing in Shihu in the opening remark of “Siji tianyuan zaxing”: “淳熈丙午沉疴少紓復至石湖舊隠.”

[18] Prunus_mume_Wiki

Meihu was not only a frequent theme in Fan’s poetry, but also the subject of his horticultural treaties Meipu 梅譜—another important work of 1186.

[19] Chang shi ji 嘗試集 was first published in Shanghai by Yadong Library 亞東圖書館 in 1920. It would be amended, revised, and reprinted thirteen times until the break of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

《嘗試集》自序_zh.wikisource.org

See also Hu Shi zuo pin ji 胡適作品集, Vol. 27 (Taipei, Yuanliu Publishing, 1986), 17.

[20] goldfishodyssey.com/revolutions-chinese-poetry-xv

hu-shih-and-chinese-language-reform_chinaheritage.net

[21] The statement was the final verse of Lu’s seven-character jueju: 江閣欲開千尺像,雲龕先定此規模。斜陽徙倚空三嘆,嘗試成功自古無。

[22] In 1952, Hu complied unpublished post-1922 works in a “preliminary selection” which later became Chang shi hou ji 嘗試後集. See Hu Shi zuo pin ji, Vol. 28, 1.

[23] English song-list in Xinshi geji (1960): “Words by Fan Ch’êng-ta[,] commentary by Hu Shih.” Zhao also cited “Contemporary Review 現代評論”—a weekly political and literary magazine—Vol. 2, No. 49, p. 16, issued on November 14, 1925, as a source of the text in his commentary. Xinshi geji, 64.

[24] 伊 was a gender neutral third person singular pronoun, commonly used in classical literature and regional dialects. In 1878, Guo Zansheng 郭贊生 in Chinese & English Grammar for Beginners 文法初階 used 伊 for the translation of “she,” 彼 for “it,” and 他 for “he.” During the new culture movement, several regular contributors of the New Youth magazine as well as organizations of the women’s movement supported the usage of 伊 as a female pronoun. The character 她, first used by Liu Bannong, gained popularity gradually and was adopted officially by the Department of Education in 1935.

[25] Liang Rengong xian sheng nian pu chang bian chu gao 梁任公先生年譜長編初稿, Part 3 下冊, compiled by Ding Wenjiang 丁文江, (Taipei, Shijie Bookstore 世界書局Taipei City, 1958), 675:

適知足下: 兩詩妙絕,可算「自由的詞」。石湖詩書後那首,若能第一句與第三句為韵—第一句仄,第三句平—則更妙矣。去年八月那首,「月」字和「夜」字用北京話讀來算有韵,南邊話便不叶了,廣東話更遠,念起來總覺不嘴順。所以拆開都是好句,合誦便覺情味減,這是個人感覺如此,不知對不對. . .

(An image of the original calligraphy of this segment is included in the above cited volume.)

Xia Xiaohong 夏曉虹 suggested that the second poem could have been “Ye shi wei yun也是微雲—Once Again Thin Clouds,” which was also set to music by Zhao Yuanren. https://m.sohu.com/n/397184866/ If this assumption were true, “Once Again Thin Clouds,” often thought to be a work of 1925, would have been written no later than August of 1924. In Zhao’s commentary on his 1926 setting, he mentioned obtaining a copy of the unpublished poem directly from Hu Shi. Xinshi geji, 63. Like “Poem on bouquets in the vase,” “Once Again Thin Clouds” was included in Chang shi hou ji.

[26] Xinshi geji, Preface, 11-12: “”

至於和聲運用的方法. . . 我在這個歌集裏頭也稍微做了一點新試驗. 第8歌 勞動歌裏 “識字讀書” 四字的主調是 232 1,底音(bass) 就作 656 1, 這也可以算是一種中國化的和聲. 第11歌教我如何不想他的過門上部作565, 第二部作123, 這種 56, 12 的[並]行五度 (parallel fifths) 在初學和聲者應該曉得避用, 但在特別加味的音樂裏不妨自由用用 . . . 561 跟 123 的配法, 我想以後都可以認為中國和聲法當中的家常便飯. 我弄的這些跟還有別的頑意兒, 並不是絕對的新發明, 五音階的和聲, Debussy 也作過些試驗了. . ..

[27] Ibid., Preface, 15.

[28] Ibid., 64

[29] An image of this calligraphy, signed 適之, can be seen in Vol. 27 of Hu Shi zuo pin ji.

[30] Ibid., Vol. 28, 17.

[31] Xinshi geji, 65.

[32] “他 He” appeared in Chang shi ji, second edition (1920), 7. Zhao Yuanren noted in the introduction to Xinshi geji (page 0) that Hu Shi thought it to be too childish: 胡適之先生嫌他太幼稚了。It was removed from the later editions of Change shi ji. In the 2nd-revised edition of Xinshi geji (1960), Zhao translated the title to the female form “she” with the remark of (i.e. China).

“小詩 Little Poem” was taken from Chang shi ji, revised edition (1922), 61.

Zhao’s self-critique reads: “頭三個是完全西洋派 (普通派,外國人看不出是哪一國人作的音樂).” Here, he mentioned a third song, likely “過印度洋 Crossing the Indian Ocean.” Xinshi geji, Preface, 12.

[33] Ibid., 13.

The fourteenth and final selection in the collection, “海韻 Hai yun” (Sea Rhyme), is a work for soprano solo and chorus.

[34] “上山 (Climbing Up the Mountain),” Chang shi ji, revised edition (1922), 67.