__ “In the Mountains 山中,” 徐志摩 Xu Zhimo

庭院是一片靜,

[ting2 yuan4 shi4 yi2 pian4 jing4]

ㄊㄧㄥˊ ㄩㄢˋ ㄕˋ ㄧˊ ㄆㄧㄢˋ ㄐㄧㄥˋ

All is silent in the courtyard.

聽市謠圍抱,

[ting1 shi4 yao2 huan2 bao4]

ㄊㄧㄥˉ ㄕˋ ㄧㄠˊ ㄨㄟˊ ㄅㄠˋ

Audible is the music from the surrounding streets.

織成一地松影——

[zhi1 cheng2 yi2 di4 song1 ying3]

ㄓˉ ㄔㄥˊ ㄧˊ ㄉㄧˋ ㄙㄨㄥˉ ㄧㄥˇ

Shadows of pines interwoven on the ground—

看當頭月好!

[kan4 dang1 tou2 yue4 hoa3]

ㄎㄢˋ ㄉㄤˉ ㄊㄡˊ ㄩㄝˋ ㄏㄠˇ

Beautiful moonlight shines high above.

************

不知今夜山中,

[bu4 zhi1 jin1 ye4 shan1 zhong1]

ㄅㄨˋ ㄓˉ ㄐㄧㄣˉ ㄧㄝˋ ㄕㄢˉ ㄓㄨㄥˉ

I wonder, in the mountains tonight. . .

是何等光景:

[shi4 he2 deng3 guang1 jing3]

ㄕˋ ㄏㄜˊ ㄉㄥˇ ㄍㄨㄤˉ ㄐㄧㄥˇ

What the scenery might be.

想也有月,有松,

[xiang3 ye3 you3 yue4 you3 song1]

ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄧㄝˇ ㄧㄡˇ ㄩㄝˋ ㄧㄡˇ ㄙㄨㄥˉ

Perhaps, there would also be the moon, the pines,

有更深曲靜。

[you3 geng4 shen1 qu1 jing4]

ㄧㄡˇ ㄍㄥˋ ㄕㄣˉ ㄑㄩˉ ㄐㄧㄥˋ

And much more profound silence.

************

我想攀附月色,

[wo3 xiang3 pan1 fu4 yue4 se4]

ㄨㄛˇ ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄆㄢˉ ㄈㄨˋ ㄩㄝˋ ㄙㄜˋ

I wish to rise up along the moonlight,

化一陣清風,

[hua4 yi2 zhen4 qing1 feng1]

ㄏㄨㄚˋ ㄧˊ ㄓㄣˋ ㄑㄧㄥˉ ㄈㄥˉ

Transform into a fresh breeze,

吹醒群松春醉,

[chui1 xing3 qun2 song1 cun1 zui4]

ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄒㄧㄥˇ ㄑㄩㄣˊ ㄙㄨㄥˉ ㄔㄨㄣˉ ㄗㄨㄟˋ

Wake up those pines intoxicated by the spring,

去山中浮動;

[qu4 shan1 zhong1 fu2 dong4]

ㄑㄩˋ ㄕㄢˉ ㄓㄨㄥˉ ㄈㄨˊ ㄉㄨㄥˋ

Float around the mountains.

************

吹下一針新碧,

[chui1 xia4 yi4 zhen1 xin1 bi4]

ㄔㄨㄟˉ ㄒㄧㄚˋ ㄧˉ ㄓㄣˉ ㄒㄧㄣˉ ㄅㄧˋ

Blowing off verdant pine needles,

掉在你窗前;

[diao4 zai4 ni3 chuang1 qian2]

ㄉㄧㄠˋ ㄗㄞˋ ㄋㄧˇ ㄔㄨㄤˉ ㄑㄧㄢˊ

Falling in front of your windows,

輕柔如同嘆息——

[qing1 rou2 ru2 tong2 tan4 xi2]

ㄑㄧㄥˉ ㄖㄡˊ ㄖㄨˊ ㄊㄨㄥˊ ㄊㄢˋ ㄒㄧˊ

Soft like a sigh

不驚你安眠!

[bu4 jing1 ni3 an1 mian2]

ㄅㄨˋ ㄐㄧㄥˉ ㄋㄧˇ ㄢˉ ㄇㄧㄢˊ

Not to disturb your peaceful rest.

__April 1, 1931

After Xu Zhimo’s marriage to Lu Xiaoman 陸小曼, his parents severed their financial support to him.[1] He took on multiple teaching jobs in Shanghai but was having difficulties sustaining her extravagant lifestyle. In winter of 1930, Hu Shi invited Xu to teach at Beijing University as well as the Women’s College. Xu’s letters to Hu dated January 28, and February 7, 1931, revealed his desire to move away from Shanghai not only for financial reasons but also for a personal and professional reboot. However, the complications of making such a move, including consents from his parents, caused him to hesitate. On February 9, he finalized the decision to accept the positions.[2]

Since Lu insisted on remaining in Shanghai, Xu became a frequent traveler between the two cities. While considering the job offer, Xu politely asked to board with Hu’s family at their new residence, 4 Miliangku Hutong (米糧庫衚衕四號).[3] Blocks away from the northern border of the Forbidden City, the alley, with its influential residents, was a gathering place for elites in the 1930s. In his letter to Lu on February 24, Xu described the comfortable setup of the guestroom on the second floor with gas heat and a bathroom nearby:[4]

眉:前一天信諒到, 我已安到北平… 胡家一切都已替我預備好. 我的房間在樓上, 一大間, 後面是祖望的房, 再過去是澡室, 房間里有汽爐舒適的很.

A courtyard lined with pines, separating Hu’s western-styled, multi-story house from the street and its clamors, was the backdrop of this poem. Without mentioning her name, Xu expressed his affections and concerns for Lin Huiyin 林徽因 who was convalescing from tuberculosis at Shuangqing Villa 雙清別墅 on Xiangshan 香山 (Fragrant Hill).[5]

Having completed her studies in America, Lin Huiyin returned to China with her newly wedded husband Liang Sicheng 梁思成 in 1928. Together, they founded the Department of Architecture at Northeastern University in Shenyang. In autumn of 1930, Xu visited them and found Lin in poor health. He persuaded her to go to Beijing for medical treatment. Soon, due to the severity of her condition, the doctors ordered her to receive care at a sanatorium. In March of 1931, Lin moved into Shuangqing Villa for a six-months seclusion with limited visitation.

In the opening stanza, we found the poet, alone in the courtyard, immersed in total silence. Born into wealth, he was experiencing serious financial difficulties—his silk garments, one torn and one burned (cigarette?), had to be mended by his hostess.[6] The heavy teaching load—new courses at two colleges—was physically demanding. This moment of peacefulness must have brought him much needed clarity and inspiration.

The moonlight, the breeze and the shifting shadows of the pines transported his thoughts to another place of similar scenery where someone he cared about deeply might be resting peacefully. He wished to be by her side yet not to disturb her—like a breeze patting her windows with pine needles.

Structurally, this poem is clearly defined with four sets of quatrains of 5-6-5-6 word counts. The rhyme scheme is ABAB, except for the odd-number lines in the third stanza. The final [ŋ/ㄥ] is used heavily in the rhymes. Technically, it involves all three disciplines in Shijing [Classic of Poetry]: 賦 fù—description—in the first stanza; 比 bi—comparison, the second; 興 xing—association, the later and more personal stanzas.[7] Instead of narrating the story, interpreters should seek to deliver the sincerity and intimacy reflected in the words.

__Chen Tianhe 陳田鶴 (1911-1955)

Chen Tianhe, birth name Qidong 啓東, was from Wenzhou 溫州 of Zhenjiang Province. His father’s surname was Zhan 詹. His mother passed away when he was nine years old. Raised by his grandparents on his mother’s side, he also took up their family name Chen 陳. He showed great interest in literature, fine arts and music from an early age. Although the family was poor, they provided him with the best education possible.

In 1928, he entered newly established Wenzhou Arts Professional School 溫州藝術專業學校, majoring in Chinese painting. Soon, he changed his focus to music under the tutelage of Miao Tianrui 繆天瑞, another Wenzhou native and one of the founders of the school.

As the school closed due to lack of funding, he transferred to Shanghai Fine Arts School 上海美術專科學校 in the following year. While there, he became friends with Li Zhongchao 李仲超. Their participation in a student protest which turned into physical clashes with the authorities led to their expulsion from the school. They were also prohibited from attending any other school in the area. To overcome such obstacles, they changed their names—Li Zhongchoa became Jiang Dingshan 江定山; Chen Qidong, Tianhe, and were accepted at the Shanghai National Conservatory of Music. They studied theory with Xiao Youmei and composition with Huang Zi.

Even though his study at the conservatory was intermittent,[8] he was the first to publish his compositions and essays among the so-called “four great disciples” of Huang Zi.[9] His early works appeared in periodicals, such as Yueyi 樂藝, Music Education (monthly)[10] and Music Magazine (quarterly). Several songs were included in Fuxing Chuji Zhongxue Jiaokeshu 復興初級中學音樂教科書.[11] In February of 1937, his first song collection Huiyi ji 回憶集 [nostalgia collection] was released in Shanghai.[12]

From August of 1936 to September of 1937, Chen worked at Provincial Theater of Shandong in Jinan 濟南. While there, he collaborated with Wang Bosheng 王泊生, a Chinese opera singer and the leader of the “new opera” movement,[13] on Yuefei 岳飛, a large stage production of 7 acts and 12 scenes, integrating traditional theater, songs, and dance with mixed instrumentation.[14] He also composed a four-act opera Jingke 荆軻 with libretto by Wang.[15] It was structured in the western style with prelude, interlude, arias, vocal ensembles, and chorus. These experiences prepared him for his large scale works in later years.

A true patriot, Chen devoted his efforts on anti-Japanese activism during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In late 1937, he gave up his work in Shandong and returned to Shanghai. He and several colleagues cofounded “Chinese Composers Association 中國作曲者協會,” publishing Zhange 戰歌 [war song] weekly. When Japanese military occupied the Chinese-controlled areas of the city, he relocated to the war-time capital Chongqing.[16] He administered training courses for music educators; edited teaching materials; and continued to write and compose—mostly patriotic songs. Works in his second song collection Jiansheng ji 劍聲集 [sounds-of-sword collection] (1943) reflected his focus of this period.[17]

Chen contributed greatly to the development of cantatas in modern China. As he fled the Japanese-controlled Shanghai, he safeguarded the manuscript of Huang Zi’s cantata Changhen ge 長恨歌 [Song of perpetual longing]—a dramatic depiction of the love story between Emperor Tang Xuanzhong 唐玄宗 and his concubine Yang Yuhuan 楊玉環, drawing inspiration from Bai Juyi’s epic poem of the same name.[18] While in Chongqing, Chen wrote Heliang huabie 河梁話別 (1943), a cantata based on the misadventure of Su Wu 蘇武 (Western Han Dynasty, c. 140 BC-60 BC)—his diplomatic expedition to Xiongnu, exile, and his unyielding loyalty to the court.[19]

In 1935, Huang Zi composed Fantasy of City Scenes 都市風光幻想曲 for the title sequence of Scenes of City Life 都市風光.[20] It was the first professionally written film score by a Chinese composer. Following in his mentor’s footsteps, Chen also wrote theme songs for several movies, mostly in art-song style with piano accompaniment. They became the pioneers of Chinese film composers.

Chen turned to teaching, collecting folk music, and score arrangements in the later years. From 1940 to 1945, he held teaching position at Qingmuguan National Music Conservatory 青木關國立音樂院. His piano accompaniments helped to popularize Man jian hong 滿江紅—a traditional tune with ci lyrics attributed to Yue Fei, and Zai na yaoyuan de difang 在那遙遠的地方 [in the faraway land]—a Tibetan folk song. In December 1949, he produced a piano reduction of the Yellow River Cantata黃河大合唱 by Xian Xinghai 冼星海 for students at Fujian Music Professional School 福建音樂專科學校. In 1951, he became of a member of the music composition team at the Beijing People’s Art Theater 北京人民藝術劇院. His assignments, however, were mostly orchestration and arrangements.

In 1953, Chen and his colleagues were sent to Yicun 伊春 in the forest of Lesser Khingan 小興安嶺, Heilongjiang Province 黑龍江省 for ideological reform. He wrote his last composition “Senlin ah! Lüse de haiyang 森林啊!綠色的海洋” [Ah forests! green ocean], a chorus work with lyrics by Jin Fan 金帆 depicting the scenery of the region. In declining health, he died of a heart attack in 1955.

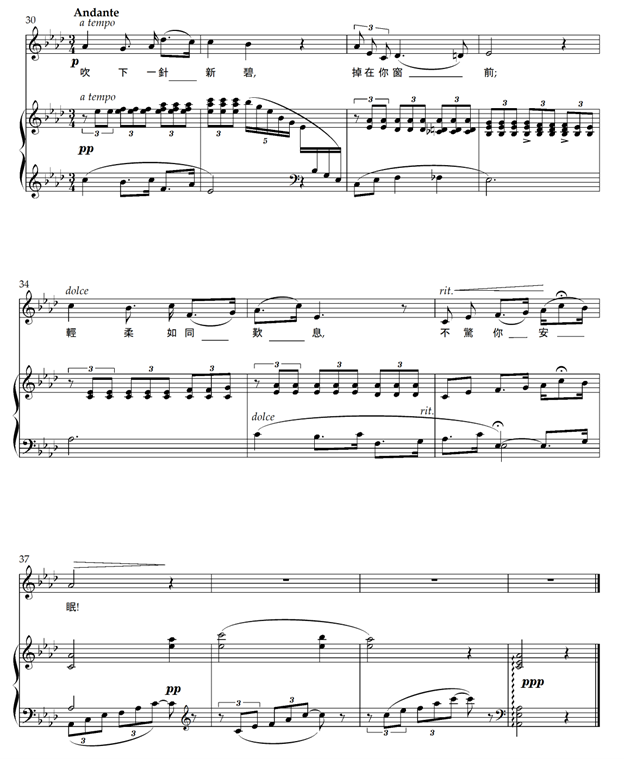

__ “Shan Zhong,” Chen Tianhe’s setting (1934)

Chen Tianhe’s setting of Xu’s words first appeared in the inaugural issue of Music Magazine (Shanghai, January 1934). The clearly defined musical sections are in accordance with the poetic structure.

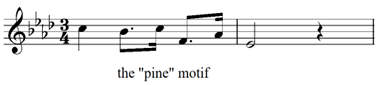

The first section, marked Andante molto cantabile, opens in A-flat major. The two-bar motif which weaves through the piece like a needle first appears in the lower voice of the piano introduction and, immediately, the opening vocal line. Since its appearances almost always link to the images of pine, it is appropriate to call it the “pine” motif:

A variation of this motif became the counter melody, paring with the voices until measure 10, corresponding to the end of the first stanza.

The first musical phrase ends with a half cadence in m. 6. The second one ends in m. 10, again on e-flat, however, fully cadenced.

As a change of thoughts, in the same measure, with a d-flat bass note, the music turns right back to A-flat major. The movements in the piano accompaniment intensify slightly in mm. 11-14, only to return to the calmness of the opening duet. The second stanza of the poem concluded in the original key quietly—”with profound silence.”

To reflect the fantastic transformation of the poet’s thoughts in the third stanza, the pace of the music increases. After a quick hint of D-flat major in mm. 19-20, the tonality shifts to its parallel C-sharp minor. Quick and light arpeggios in the piano part emulate the gentle breeze, flowing freely. Large leaps and chromatic movements in the vocal part throughout the section reveal the hidden emotions in the words.

The “pine” motif in the piano part in mm. 30-31 brings back the calmness of the opening section. A slightly-extended version of the motif, gently exchanged between the voice and the piano, concludes the final stanza of the poem.

“Shan Zhong” is a carefully designed work, organized in its structure and imaginary in its details. It is full of Chinese characters without intentionally “being Chinese.” For singers, the primary technical challenge is to carry out smooth phrases. In the middle—Allegretto—section, the voice must be well-balanced between registers. The pianist must take on the role of an intimate partner, threading through all the emotional changes and be sensitive to all the symbolic features. Whether the repeating chords in the opening section or the flowing arpeggios in the middle, all the technical issues must be skillfully handled. The utmost important task for both performers is to deliver the emotional vulnerability sincerely.

[1] For biographical details of Xu Zhimo: goldfishodyssey.com_chinese-poetry-xvii-chance-encounter-偶然

[2] Xu Zhimo Quanji 徐志摩全集 [The complete works of Xu Zhimo], ed. By Han Shishan 韓石山, Tianjin ren min chu ban she, Tianjin city, 2005, vol. 6—Letters, 259-264:

一九三零年冬

適之: . . . 上海學潮越來越糟, 我現在正處兩難, 請為兄約略言之. . .. 凡此種種, 仿彿都在逼我北去, 因南方更無教書生計, 且所聞見類, 皆不愉快事. 竟不可一日, 居然而遷家實不易知.

一九三一年一月二十八日

適哥:. . . 此函到時, 當已安人米糧庫, 胡太太弗復憂矣. . . 上海今實如大漠矣, . . 爲我自身言至願北遷. 況又承兄等厚意, 爲謀生計若弗應命, 毋乃自棄. 然言遷則大小家庭尚須疏通而外, 遷居本身亦非易之.

一九三一年二月七日

適哥:連接兩函及電至謝. . . 但我實在有不少爲難處. . . 上海生活, 於我實在是太不相宜, 我覺得骨頭都懶酥了, 再下去真有些不堪設想. 因此我自己爲救己, 的確想往北方跑, 多少可以認真做些事. . . .我如果去自然先得住朋友家, 你家也極好.先謝.

一九三一年二月九日

適之:你勝利了,我已決定遵命北上,但雜事待處理的不少. . . 到北京恐怕得深擾胡太太, 我想你家比較寬舒, 外加書香得可愛, 就給我樓上那一間吧.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid, 150.

[5] Fragrant_Hills_Wiki

[6] Xu Zhimo Quanji, 150.

[7] goldfishodyssey.com_chinese-poetry-i-classic-of-poetry-詩經

[8] Chen’s study was interrupted the first time in 1932 when the conservatory shut down after the January 28 Sino-Japanese conflicts in the Shanghai International Settlement. The financial difficulties of his family forced him to take on various jobs while studying part-time. In 1935 and 1936, he resumed full-time study but only for one term each time. He never completed his study at the conservatory.

[9] Chen Tianhe, Liu Xue’an 劉雪庵, Jiang Dingshan, and He Luting 賀綠汀 are known as the “four great disciples 四大弟子” of Huang Zi.

[10] See commons.wikimedia.org_音樂教育_1934年2卷1期.pdf This is a special issue on elementary school music education.

[11] Fuxing Chuji Zhongxue Jiaokeshu 復興初級中學音樂教科書, Commercial Press 商務印書館, Shanghai, 1933-1935. It is a 6-volume music teaching series edited by Huang Zi and his colleagues

[12] Huiyi ji 回憶集, Zhonghua Publishing 中華書局發行所, Shanghai, 1937. commons.m.wikimedia.org_回憶集.pdf

[13] Wang Bosheng 王泊生 (1902-1965) specialized in “lao sheng”—elderly male character in Peking opera. He was committed to transfer traditional theater into “new opera.”

[14] Yue Fei (1103-1142) was a patriotic hero of the Southern Song Dynasty. Yue_Fei_Wiki

[15] Jin Ke (?-227 BC) was a knight of the Warring State period, known for his heroic but failed mission to assassinate the tyrannical King Zheng of the Qin State—later the first Emperor of China. Jing_Ke_Wiki

[16] Japanese military did not enter the International Settlement and French Concession until 1941. Even though commercial and cultural activities continued with foreign supports, these areas became isolated from the rest of the city. Therefore, this period between 1937 and 1941 was often referred to as “Solitary Island Period 孤島時期.”

[17] Jiansheng ji 劍聲集, Dadong Bookstore 大東書局, Chongqing, 1943. It was the only collection of an individual composer during the war time. commons.m.wikimedia.org_/劍聲集.pdf

[18] The libretto of Changhen ge was written by Wei Hanzhang韋瀚章. The titles of individual movements were taken from Bai Juyi’s poem. The work consisted of ten movements. The fourth, seventh, and nineth movements were incomplete at the time of Huang Zi’s death. Lin Shengxi 林聲翕, Huang’s pupil, completed and edited the work with Wei in 1972.

[19] In the Preface to Heliang huabie 河梁話別, Lu Qian 盧前, the librettist, detailed his early encounter and collaboration with Chen Tianhe, his colleagues at the Music Educators Training Course 音樂師資訓練班 in Shapingba 沙坪壩 in 1939. Chen admired Lu’s lyrics and encouraged him to write a long-form cantata [康達達]. Inspired by Su Wu’s biology in Hanshu 漢書, he completed the libretto in ten days. Although the scores of a few individual movements were in circulation, the completion of the entire work came much later in autumn of 1943. It was published by Yongkui Music Printing Press 詠葵樂譜刊印社 in January 1946 in Chengdu 成都.

commons.wikimedia.org_河梁話別_清唱劇.pdf

[20] Youtube_Huang-Zi-Fantasia of City Scenes