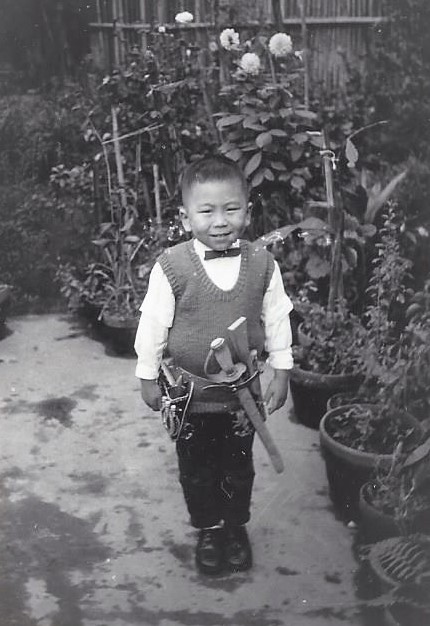

I might have been ten- or eleven-years-old, already had a sense of self-awareness. Mom handed me a yellowing old photo and asked me if I knew the person in the picture. I was perplexed seeing a male version of myself looking back at me.

Dad never talked about his past. Never once. The only thing linking us to his previous life was a photo of our grandmother. It was taken outdoors. Grandma sat on a chair not showing too much emotion. Still, she seemed gentle but in control. The photo was in a simple frame, placed high on a shelf most of the time. On Chinese New Year’s Eve, we would bring it down and set it on the table with all the celebratory dishes.

From time to time, mom told us that our grandfather was a Chinese medicine doctor. He was generous with people and had great reputation. However, he died young. Mom said that dad grew up poor and that he used to read books while herding water buffaloes. He received scholarship to attend high school and college in Japan. The photo that mom showed me was taken during those years.

Whether dad was hoping for a son or not, he loved me. I was told that his first report to mom was: “She is beautiful. Maybe she will win Miss China pageant one day.” Our bound was instant and innate.

My nose is straight and tall. Dad loved to pinch its narrow bridge. I disliked his squeezes as much as his occasional kisses on my cheeks. His unshaven face rubbed against my skin, sticky and prickly. I would always push him away. Sometimes, he would press on my chin, complaining about its thinness. Later, he would pull on my brother’s large earlobes. They were round and fleshy—signs of good fortune.

Dad wasn’t very hands-on with our education. Whenever he disagreed with mom’s philosophy and approaches, he would voice his concerns sternly. In contrast to mom’s harsh discipline, dad’s soft guidance seemed to have influenced me more over time.

Dad didn’t go out often. He would leave in time for his lectures at the universities and came straight home. He stayed up most nights reading and writing and slept in late. I used to stand close to his bed watching him; watching his chest gently expand with every breath. My fear of losing someone who loved me so dearly would dissipate for that moment.

Dad was never a celebrity to the general public. But his works were widely read. His translations of German Lieder were taught at schools. Many of my teachers knew and remembered me as his daughter. It put some pressure on me to behave properly and to study hard, especially in literature and music.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease began to slow down dad’s work shortly after he turned seventy. By my undergraduate years, his steps became unstable; he started talking less and less; he wouldn’t be able to eat by himself. He attended my graduation, walking slowly on canes.

Soon after that dementia and related issues set in. Dad was in and out of hospitals often. Mom, my brother and my stepsister cared for him. I, on the other hand, didn’t really do enough for him. The changes in him were difficult for me. I started working and was getting ready to study abroad. Everyone at the hospital told me that dad was happiest seeing me. He would always hold my hand and told me that he owed me apologies. . . Because of his conditions, it was difficult to tell whether he didn’t want me to see him suffering or he was still troubled by old family feuds.

I took TOEFL and passed it with decent marks on the first try. It became more and more certain that I would go abroad for my graduate study. Even with dad’s worsening conditions, mom consulted with him. He said: “She always wants to leave. Let her go.”

1983 must have been an extremely difficult year for mom. Father passed peacefully on April 3. I left for the United States four months later. She was fifty-seven years old.