__ Not a Flower 花非花

唐, 白居易

Tang Dynasty, Bai Juyi

花非花,霧非霧。

[hua1 fei1 hua1 wu4 fei1 wu4]

ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄈㄟˉ ㄏㄨㄚˉ ㄨˋ ㄈㄟˉ ㄨˋ

Delightful like a flower, yet not a flower;

Transient like fog, yet not fog.

夜半來,天明去。

[ye4 bang4 lai2 tian1 ming2 qu4]

ㄧㄝˋ ㄅㄢˋ ㄌㄞˊ ㄊㄧㄢˉ ㄇㄧㄥˊ ㄑㄩˋ

Arriving in the middle of the night;

Departing as the day breaks.

來如春夢不多時,

[lai2 ru2 chun1 meng4 bu4 duo1 shi2]

ㄌㄞˊ ㄖㄨˊ ㄔㄨㄣˉ ㄇㄥˋ ㄅㄨˋ ㄉㄨㄛˉ ㄕˊ

It arrives like a euphoric dream,

lasting only momentarily,

去似朝雲無覓處

[qu4 si4 zhao1 yun2 wu2 mi4 chu4]

ㄑㄩˋ ㄙˋ ㄓㄠˉ ㄩㄣˊ ㄨˊ ㄇㄧˋ ㄔㄨˋ

It departs like morning clouds,

vanishing into obscurity.

__Bai Juyi (772-846 AD)

Bai Juyi 白居易, courtesy name Letian 樂天, along with Li Bai 李白 and Du Fu 杜甫, was one of the most influential and prolific poets of the Tang Dynasty. In a letter to his close friend Yuan Zhen 元稹, Bai described his lifelong efforts and struggles as a poet: He began studying poetry when he was about five-six years old and appreciated rhyming thoroughly at the age of nine. After turning fifteen, while preparing for the Imperial Exams, in order to continue writing poetry, he gave up sleeping and suffered physical pains.[1]

He passed the Jinshi degree of the Imperial Exams in 800 (德宗貞元十五年) and began his governmental career. His straightforwardness and frequent violations of formality caused many rises and falls of his political fortunes which endured the reigns of eight emperors. He officially retired in 842 (武宗會昌二年). In “Chishang pian 池上篇,” a poem of 829 (太和三年), and “Zuiyin xiansheng zhuan 醉吟先生傳,” a prose of 838 (開成三年), Bai described his later years in detail. He spent most of his time at a thoughtfully designed residence in the southeastern part of the capital city Luoyang. He found joy in days filled with reading, music making, good wine, and frequent visits of close friends, among them the monk Ruman 如滿. His late works often showed influence from Buddhism and Taoism.

As an official, Bai cared very much about the lives of ordinary people. As a poet, he strove to make his work approachable to all. Huihong 惠洪 (1071-1128), a Buddhist monk of the Northern Song Dynasty, in Lengzhai yehua 冷齋夜話, a notebook of miscellaneous subjects, accounted that, whenever Bai Juyi created a new poem, he would hand it to an old woman. If she understood it, he would keep it. Otherwise, he would edit or rewrite the work.[2] Critics faulted him for lack of sophistication.

Bai believed that poetry should be realistic and truthful. With this conviction, he and Yuan Zhen led a “new yuefu movement 新樂府運動,” seeking to revive the folk-like style of Shijing 詩經 [the Classic of Poetry]. Bai explained in the preface to his New Yuefu, a collection of fifty poems:[3]

- There are no fixed numbers of words or verses. Word- and verse-lengths are set according to the contents of the poems, and not versification.

- Following the style of Shi sanbai 詩三百 [three hundred poems—Shijing], the titles are given in the opening verse of each poem. The ending verses should indicate its subject matter and purpose.

- The words are genuine and simple so that whoever reads them can understand. The discourses are straightforward and heartfelt so that whoever hears them will be affected deeply. The narratives are true and verified so to deliver credible information. The style is fluent and without constraint, suitable for musical works and songs.

- In short, these words are written for rulers, for statesmen, for commoners, for subjects, for facts, but not [simply] as literary works.

This statement attested to Bai’s devotion to being a poet for all people. He died in 846 and was buried in Luoyang. Over three thousand of his works are still in circulation.

__ “Not a Flower 花非花”

In his poetic collection Bai shi changqing ji 白氏長慶集 (824), Bai Juyi categorized the poems first by their characters then grouped them by their styles/structures. “Hua fei hua 花非花” was found among the twenty-nine sentimental [感傷] poems in chapter 12.[4] Structurally, Bai marked this group of poems as “ge, xing, qu, yin—mixed-style 歌行曲引雜體.” All four styles are descriptive works often associated with music or songs.[5]

The poem is of single stanza and six verses. The first four three-word verses resemble the opening verses in Bai’s new yuefu poems. Verses five and six are of seven words, similar to a couplet in jueju or lüshi. Lines two, four and six are rhymed.[6] This particular structure later became one of the tone patterns in ci poetry, named after its opening words.

The precise subject matter of the poem was not given. Many believe that the poem refers to a lost love, to life in general, or a brief night encounter. In plain texts, the poet depicted an ephemeral object, beautiful as a flower and mysterious like the fog, with very little emotional attachment. These short verses read more like a Buddhist gatha than a personal reflection.

__Huang Zi and his music

The art songs created throughout the 1920s were mostly experimental in nature. Their composers, though highly intelligent and well-trained, were amateurs. Huang Zi 黃自, having studied at Oberlin and Yale, returned to China and devoted his time in music education and composition. As a faculty member of the National Conservatory of Music from 1929 till his untimely death in 1938, he nurtured a generation of young composers, including Chen Tianhe 陳田鶴, Liu Xue’an 劉雪庵, Lin Shengyi 林聲翕, and He Luting 賀綠汀. Collectively, they furthered the development of Chinese art songs.

Zhao Yuanren gave a very sincere assessment of Huang Zhi’s musical works in a article, published in Ta Kung Pao 大公報 on May 9, 1939—commemorating the anniversary of Huang’s death.[7]

. . . If we simply wanted to look for someone who could write music that westerners would “totally enjoy,” there would be plenty of people. . . . But composers who [were capable of] assimilating western techniques so they became second nature, then using them to deliver various features derived from Chinese background, Chinese life, Chinese environment, and could do so with ease—not only writing with ease themselves but also allowing the audience to listen with ease—were what we missed the most.

Huang Zi’s melodies were fluent. When he wished to sing a note, he would fully prepare a path for it so [the melody] would move towards it naturally. He would not set a note strenuously just to create a nice-sounding phrase.

Huang Zi’s rhythmic approaches were, of course, diverse. Generally, they tended to be steady. . . . Huang Zi was extremely demanding on the synergy between the inflections of the Chinese texts and the musical phrases. . . . To make things more interesting, less talented people often risk violating the rules; to observe the rules strictly, they run into obstacles here and there. Only Huang Zi was capable of following the inflection of the verses closely without the writer or the audience feeling restrained, as if they were to be sung that way from the start.

Huang Zi’s harmony was mostly uncomplicated, just like the person. Modulations were generally to the closest keys such as the dominant or relative minor, even the enharmonic major-minor transitions were rare. For instrumental music, . . . due to the different nature, the applications of harmony were therefore more complex. Nonetheless, he was always adept at drawing from the most economical means to achieve the greatest musical interests.

Huang Zi’s counterpoint was also very natural. He did not have to play fancy tricks to make the call-and-response flow smoothly. Huang Zi did not compose many works. Nor do we need to, for rhetorical reasons, call him a great contemporary composer. His strength was that, whatever he had in mind, he achieved it—always pertinent, and always very easy to sing. I have called him the most “singable” composer of the modern China.

__ “Hua fei hua,” Huang Zi’s setting (1933)

In the essay “Yinyue xinshang 音樂欣賞” [music appreciation], first printed in the inaugural issue of Yueyi 樂藝 (1930), Huang wrote: “Reading Bai Leitain’s ‘Pipa xing 琵琶行’ was my favorite thing to do when I was little. At that time, I was too young to fully understand the meaning of the words, let alone to appreciate the profound message of the poem. I liked it, simply because of its resonant inflections—pleasing to the ear. . . .”[8] There was clearly a meeting of the mind between the poet and the composer: Though living thousands of years apart, they were both keenly sensitive to the musicality of words—its importance and applications.

Huang’s setting of “Hua fei hua” first appeared in the first volume of Fuxing Chuji Zhongxue Jiaokeshu 復興初級中學音樂教科書, 第一冊—a series of musical teaching materials for middle schools.[9] It was clearly created for young students. Unlike many contemporary “school songs,” it did not seem to be written for the purpose of “character building”—rather, for music and literary appreciations.

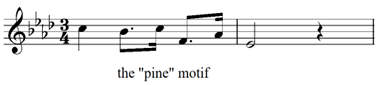

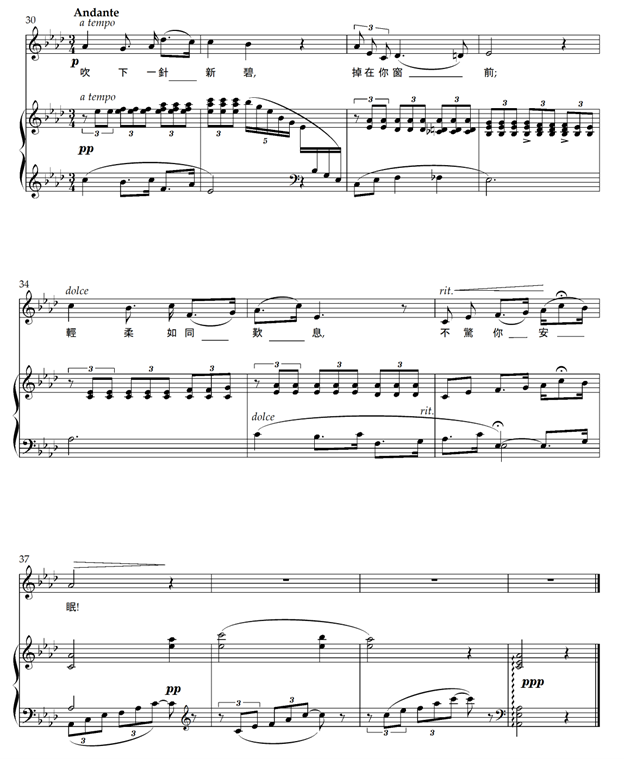

Uncomplicated, it is through-composed and only ten measures long, including two measures of introduction. The piano doubles the melodic lines in octaves. The middle voices provide simple harmonies at a steady pace gently. The original key, based on western theory, is in D major. Following this theory, there are only two cadential points: one in measure 2—the end of the piano introduction, and another one at the end of the piece. Instead, the song is punctuated by four melodic phrases, two measures each. Measures 4 and 8 end on B minor chords; measure 6, on E minor—far from the dominant and subdominant of D major. The lack of harmonic direction, using western terms, is likely intentional, subtly mirroring the fugitive nature of the texts. The elegant melodic line, extremely accessible to professionals and amateurs alike, is what makes this song memorable.

Huang Zi did not leave behind a large body of works when he died of typhoid fever at the age of 34. His students at Shanghai Conservatory carried on his work as both composers and educators. During the Cultural Revolution era, his works were banned due to his ties to the Nationalist government. Nevertheless, in the recent decades, his influence on Chinese musical culture in the twentieth century regained much deserved recognition.

[1] 《與元九書》”Letter to Yuanjiu,” Bai shi changqing ji 白氏長慶集 (824—長慶四年), chapter 卷 45.

白氏長慶集, 卷45_zh.wikisource.org

[2]冷齋夜話, 卷一 (Lengzhai yehua, volume 1), <老嫗解诗>: 白樂天毎作詩,令一老嫗解之,問曰:「解否?」嫗曰解,則録之;不解,則易之。故唐末之詩近於鄙俚。This was the anecdotal origin of the idiom “老嫗能解 loayu nengjie” (old woman can understand).

[3] Xin Yuefu 新樂府 [new yuefu], (809—元和四年), Preface 序曰:凡九千二百五十二言,斷為五十篇。篇無定句,句無定字,繫於意,不繫於文。首句標其目,卒章顯其志,詩三百之義也。其辭質而徑,欲見之者易諭也; 其言直而切,欲聞之者深誡也; 其事核而實,使採之者傳信也; 其體順而肆,可以播於樂章歌曲也。總而言之,為君、為臣、為民、為物、為事而作,不為文而作也。

[4] Bai shi changqing ji 白氏長慶集, 卷12: 感傷四, 歌行曲引雜體, 凡二十九首.

[5] 《樂府詩集》, 四庫全書, 集部八, 宋, 郭茂倩撰, 卷六十一, 雜曲歌辭, 序云:“漢、魏之世,歌咏雜興,而詩之流乃有八名:曰行,曰引,曰歌,曰謠,曰吟,曰咏,曰怨,曰嘆,皆詩人六藝之餘也.

Yuefu shiji [Collection of Yuefu poetry], Sikuquanshu, Ji section 8, edited by Guo Maoqian, Chapter 61, “Lyrics for Miscellaneous Songs”, preface: “During the Han and Wei periods, a variety of songs and recitations were created. In addition to the six categories mentioned in Shijing, there were eight poetical styles, namely: xing, yin, ge, yao, ying, yong, yuan, tan.”

“Changheng ge 長恨歌” [Song of perpetual longing] and “Pipa xing 琵琶行” [Ballad of pipa], two of Bai’s most beloved long narrative poems, are in such styles.

[6] Although the word 去 [qu/ㄑㄩˋ] does not rhyme with 霧 ㄨˋ and 處 ㄔㄨˋ in Mandarin, all three words belong to the rhyme group “遇” 攝 [yu she] in Guangyun 廣韻, a rhyme dictionary of Middle Chinese. There are sixteen 攝 /she in Guangyun, each includes words of the same final but not always in the same tone.

[7] Ta_Kung_Pao_(1902-1949)_Wiki

Ta_Kung_Pao, May 9, 1939, P7:

⋯單是要找能寫出譜來使西洋人能「透透的欣賞了」的,那有的是人⋯但是把西洋音樂技術吸收成為自己的第二天性,再用來發揮從中國背景,中國生活,中國環境裏的種種情趣,並且能用的自自如如的,—不但自己寫的自自如如,連聽者也能覺得自自如如的,—這種作曲家是我們最缺少的。

黃自的旋律是流暢的。他要唱一個什麼音,他先給充分預備好了去路,待會兒自自然然就會到那兒,絕不爲了唱一句好聽的東西硬裝上去。

⋯黃自的節律當然是變化很多。大體上說起來是頃向穩重派⋯黃自對於中國字在樂句裏輕重音的配置,可以說嚴格的要命⋯⋯天才差一點的人,爲使作物有趣,往往有犯規的危險。爲了嚴格的守規,又弄得東怕撞板西怕碰釘子。只是黃自他嚴守了詞句的節律而作者聽者都不覺得節律的拘束,好像詞壓跟兒就是這麽唱似的。

黃自的和聲大半是樸實的如其爲人。轉調都轉到上五度或下三度的短調等等極近的調,甚至同主音的長短調互轉都用的不頂多;在器樂裏⋯因爲性質不同,當然用的和聲也複雜得多,但是他總是善於以最經濟的和聲材料來得到最大可能的音樂興趣。

⋯黃自的對位也是非常自然的。他不用玩多少奇怪的花樣就可以你一問我一答的唱得很熟; ⋯黃自所作的音樂並不多,我們也不必爲了作文章的緣故說他是現代一個偉大的音樂家。他的長處是做什麼像什麼,總是極得體,總是極好唱,我曾經稱他為現代中國最可唱 (Most Singable) 的作曲家。

[8] Huang Zi, “Yinyue de xinshang 音樂欣賞,” Yueyi 樂藝, Vol. 1, No. 1 (April 1930), 26:

“⋯我小的時候,最喜歡讀白樂天的《琵琶行》。當時年幼,連字的意義都不能完全了解,更談不到什麼領略詩中的深意。我喜歡他,只因爲它的音節鏗鏘,念起來很好聽。⋯”

The article was based on a speech given on December 3, 1929, at Shanghai Fine Arts School 上海美術專科學校.

[9] Fuxing Chuji Zhongxue Jiaokeshu 復興初級中學音樂教科書, Commercial Press 商務印書館, Shanghai, 1933, Vol. 1, 50

復興初級中學音樂教科書, Vol. 1, PDF_commons.m.wikimedia.org