For thousands of years, Classical Chinese was the unique written language for literary and documentary works alike. On the other hand, due to the vastness of the land and the geographic attributes—especially those of major rivers and mountains, there was no common spoken language in China. Under the umbrella of Sinitic languages, spoken by the Han 漢 people, there were numerous branches of dialects including Mandarin 官話, Jin 晉, Wu 吳, Xiang 湘, Min 閩, and Hakka 客家, to name a few. Each of them was further divided into a great number of regional tongues.[1] More than accentual variants, these dialects share few commonalities and were mostly unintelligible to outsiders.[2]

Zhao Yuanren recounted his linguistic experiences as a young person: His family communicated in northern dialects. However, the old masters who taught him poetry and Classical literature spoke southern dialects. For a long time, he thought that northern tongues were for daily conversations, and only the southern dialects were to be used in reciting literature.[3]

Efforts were made in early 1920s to unify the spoken languages.[4] A standardized system based on the Peking (Beijing) dialect was established to be the “national language” 國語.[5] The pronunciation principle of this language would form the foundation for proper diction in Chinese art songs.

In the following discussions, transliterations in pinyin (in italics), Romanization and Zhuyin will be quoted in brackets. For convenience and clarity, instead of diacritical marks, numbers will be used for tone indications in pinyin. When IPA symbols were used for clarification, they will be marked with slashes. The tone numbers in IPA—55, 35, 214, 51— are based on the tone letter system devised by Zhao Yuanren. Further details can be found in later sections of this article

When learning texts in western languages, singers often rely heavily on the spelling combinations and the pronunciation principles of each language. Due to some unique linguistic practices, when studying Chinese texts, in addition to knowing the sounds of consonants and vowels and learning to differentiate tones, several lexical semantics must be taken into consideration.

–Literary vs colloquial

Certain Chinese words have literary and colloquial pronunciations. While the choice of pronunciation will not alter the meaning of the text, it highlights the style. The language of refined literature should not be equated to colloquial Pekingese. While modern pronunciation is suitable for vernacular poems, modifications should be applied to traditional poetry. For example:

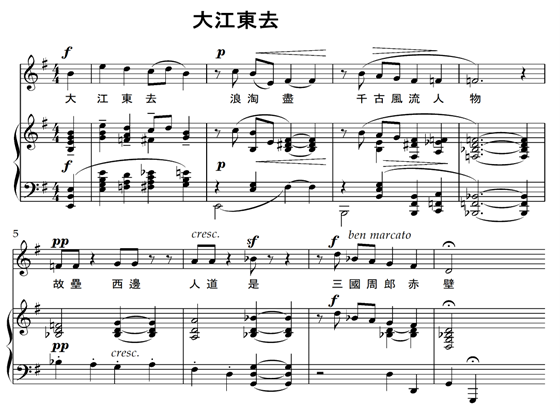

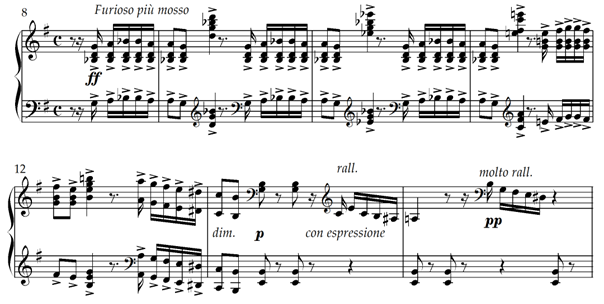

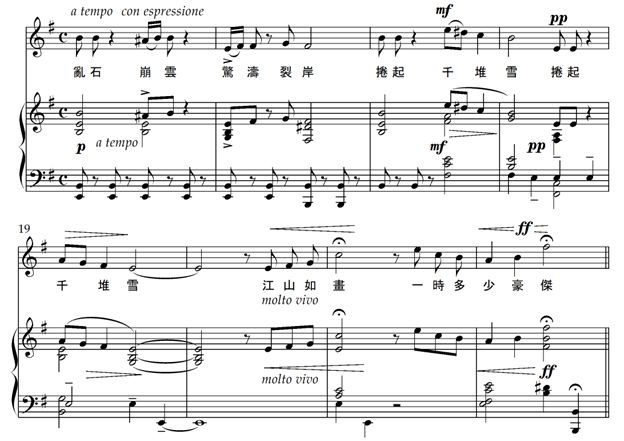

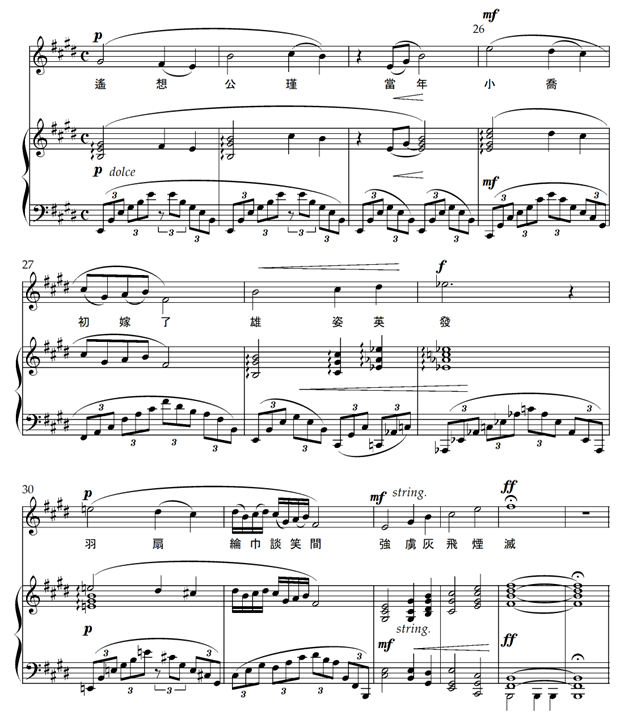

還, when meaning “still,” is pronounced [hai2] in daily usage. For poetic reading, it is pronounced [huan2].[6] The well-known verse “乍暖還寒時候” in Li Qingzhao’s “shēng-shēng-màn” 聲聲慢 should be read as: [zha4 nuan3 huan2 han2 shi2 hou4]. The final words in Su Shì’s “The Great River Flows Eastwards” 大江東去should be “一樽還酹江月” [yi4 zun1 huan2 lei4 jiang1 yue4]. Zhao Yuanren suggested a third pronunciation [han2], derived from southern mandarin, for 還 in his songs as it would be less casual but not too traditional.[7]

The conversational pronunciation of the adverb 了 is /lə/[8] in neutral tone—light and staccato. In literature, it is often pronounced as [liao3] in the third tone. The possessive particle 的 is spoken as /də/ in neutral tone. In lyrics, especially when legato e espressivo, it will be read as [di]. The conversational pronunciation of the conjunction 和 (meaning “and”) is [han4]. The literary version is /hə35/ in the second tone.

__Heteronyms 破音字

There are endless heteronyms in Chinese language. It would be necessary to understand the usages of words in context. Following are a few frequently used characters and their various pronunciations and meanings:

得[9]

•When meaning “obtain,” “receive,” “suitable,” or “content,” /də35/ in the second tone, [de2]

•“Must,” [dei3] in the third tone

•Used as an adverb, it is pronounced as /də/ in neutral tone.

•In traditional literature, it would be read as /də35/, [de2]. Li’s “shēng-shēng-màn” would end with 了得 [liao3 de2].

的[10]

•“Target,” or “aim,” is pronounced [di4].

•“Certain,” or “truly,” it will be in the second tone as [di2].

和[11]

•“Peace,” “ease,” or “smooth,” is pronounced /hə35/, [he2]

•“To respond,” “to be in concert with,” “to echo,” /hə51/, [he4]

•“Mix,” or “combine,” [huo4][12]

•“Warm,” [huo5] in neutral tone.

更[13]

•Noun, a two-hour division of night, marked by gongs of sentry,” /kɤŋ⁵⁵/, [geng1].[14] Colloquially, [jing1]. “挨不明更漏” in Cáo Xuěqín’s “Verses of Red Beans” 曹雪芹, 紅豆詞should be read as [ai2 bu4 ming2 geng1 lou4].

•Verb, “change,” “alternate,” /kɤŋ⁵⁵/, [geng1]

•“More,” “further,” /kɤŋ51/, [geng4]

曲[15]

•Noun, “tune,” “melody,” or a poetic form, [qu3]

•Adjective, “bend,” or “curvy,” [qu1]

Once the syntax was understood, phonetic characteristics also require careful handling and adjustments in singing.

__Phonetic symbols and transliterations

Phonetic symbols were devised to classify and transcribe sounds. As supplementary tools, they can be helpful to beginners. However, with great limitations, phonetic symbols are no substitute to linguistic study.

Most Classical musicians are familiar with International Phonetic Alphabets. In European languages, the symbols largely resemble the corresponding letters, thus not too difficult to apply. The same cannot be said for symbols used to mark Chinese sounds. In some cases, these symbols can be used for differentiation and clarification. Otherwise, they should be reserved for linguists and phonologists.[16]

There are several systems of Chinese Romanizations—using Latin alphabets to transliterate Chinese characters.[17] The earliest system was created by the Jesuits in the 16th century. The Wade-Giles system developed in the late 19th century was the first to be used universally.[18] The Yale romanization of Mandarin was devised for teaching Chinese to westerners, especially American soldiers in mid-20th century.[19] Although both the Wade-Giles and the Yale systems have been largely replaced by Hanyu pinyin, the former is still used in transliteration of proper names in Taiwan; the latter, in western textbooks.

Among transliteration systems created by native Chinese, three are most noteworthy: Zhùyin fúhàu 注音符號, Gwoyeu Romatzyh 國語羅馬字, and Hànyǔ Pinyin 漢語拼音.

In the last decades of the Qing Dynasty, as part of the initiative to promote literacy, linguists and educators tried their hands on building a transliteration system. On June 10, 1908, Zhang Taiyan presented two sets of symbols in his article “駁中國用萬國新語説” (“Refuting the Discourse of Using Esperanto in China”) in 《民報》Min Bao (People’s Newspaper)—a revolutionary paper published in Tokyo.[20] Inspired by the application of Katakana, a Japanese syllabary system derived from radicals of Chinese characters, Zhang patterned his phonetic symbols on ancient seal script 小篆.[21] The first set of symbols are thirty-six niǒu-wén 紐文, representing initials/consonants; the second, twenty-two yùn-wén 韵文, rhymes/final/vowels.[22]

In 1912, the temporary government in Beijing 北洋政府 established The Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation 讀音統一會 led by Wu Zhihui 吳稚暉.[23] Adopting fifteen symbols created by Zhang Taiyan and, with the same approach, adding new ones, the Commission proposed a set of thirty-nine symbols, Zhùyin zìmǔ (phonetic alphabets, 注音字母). After dropping a few symbols used only in dialects, the Ministry of Education of the Republic government formally published of thirty-six symbols in 1918. The system went through several modifications and was rename Zhùyin fúhàu (phonetic symbols) in 1930.[24]

These symbols are the most direct references to the phonology of Mandarin Chinese. On the other hand, their nonuniversal features make its application challenging for westerners. Replaced by Hànyǔ pinyin in China, these symbols are still in use in Taiwan and have been adopted for use in a few dialects.

Rather than a phonological system, Gwoyeu Romatzyh 國語羅馬字 (GR) was designed to be a writing system of Chinese words. Conceptualized by Lin Yutang 林語堂 and developed by Zhao Yuanren between 1926 and 1928, GR was characterized by its “tonal spelling”—an intricate and strict spelling system as indicators for the four tones in Mandarin.[25]

Zhao explained the system in the “Lyric Diction” section of his New Poetry Songbook to the readers/musicians and provided a list of spelling for all 480 words appeared in the collection.[26] In most cases, tonal indication letters were added to the basic spelling of the words. These letters were not sound components and, therefore, would not alter the pronunciations of the original consonants and vowels. The voiced consonant m, n, l, r in the first tone would be written as mh, nh, lh, rh. The second tone would often be indicated by an added “r” after the vowel. Double vowels such as aa-, ee-, ii-, uu, are indicators of the given vowels in the third tone. Double consonants, e.g., nn- and ll-, signaling the fourth tone.

In other cases, alternating letters would be used: Initial i-, u-, and iu- only occurs in the first tone. They would be changed to y-, w-, y(u) in the second and the fourth tones, and to e-, o- in the third. Certain combination of vowels would require further modifications.[27]

The other significant feature of GR is the combination of words into meaningful units without separating them with spaces. The initial verse of “The Great River Flows Eastwards,” 大江東去, 浪淘盡, would be presented as: [dahjiang dongchiuh lanqtaurjinn]

GR was published by the Republic government as the standard spelling system in 1928. Zhao used the system in his Mandarin Primer (1948) and Grammar of Spoken Chinese (1968). Lin Yutang used it in his Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage (1972).[28] Yet, the cumbersome spelling rules made its application challenging to most users.

The most widely known and universally adopted Chinese spelling system is Hànyǔ pinyin (literally, Han language spelling/spelt sounds). Its roots can be traced back to Beifangxua Latinxua Sin Wenz 北方話拉丁化新文字 (Latinized new script of the northern language) developed by Soviet Scientific Research Institute on China between 1928 and 1931. The system was endorsed by many Chinese intellectuals including Lu Xun 魯迅, Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培, Sun Ke 孫科, and Guo Moruo.郭沫若 and was used in over three hundred publications.

In the early 1940s, Sin Wenz was popularized in the communist-controlled Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region 陝甘寧邊區.[29] On December 25, 1940, the administration of the SGNBR decreed that Sin Wenz should have the same legal status as the traditional characters.[30] However, it quickly went out of fashion.

After taking control of China in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party embarked on language reform and established State Language Committee 國家語言文字工作委員會immediately. In addition to promote Pǔtōnghua (普通話 standard Mandarin) and simplifying the traditional characters, the Committee also took on the task of developing a Romanized writing system. A group of linguists, led by Zhou Youguang, constructed Hànyǔ pinyin. Its spelling system was based on GR and Sin Wenz. The tone diacritics were taken from Zhuyin. Pinyin was approved 1958 by People’s Congress and adopted by International Organization for Standardization as an international standard writing system in 1982.

Transliterations of Chinese characters, be it in GR, Sin Wenz or Pinyin, can be helpful tools for non-native speakers, especially English or European language speakers. Nevertheless, when the letters are used to represent sounds that do not exist in western language, they can easily lead to mispronunciations. Similar to IPA, they should be used as supplementary tools and with great care.

__Syllabic consonants

A syllabic consonant is a consonant that forms an individual syllable, such as the “l” in “bottle,” the “m” in “rhythm,” and the “ng” in “morning.” There are seven syllabic consonants in standard Chinese. They are: zi-, ci-, si-, zhi-, chi-, shi-, ri in pinyin; and/orㄗㄘㄙㄓㄔㄕㄖin Zhuyin symbols.[31]; All of them are apical consonants, produced by sending air through a narrow passage between tongue, alveolar ridge, and teeth.

[Zi-/ㄗ] is similar to “-ds” in “beds;” [ci-/ㄘ], “-ts” in “cats;” and [si-/ㄙ], “s” in “Sam.” To pronounce these sounds perfectly, the tongue position must be flat and with the tip against the lower teeth.

The sound of [Zhi-/ㄓ] is closed to “-ge” in “judge;” [chi-/ㄔ], the initial sound of “church;” and [shi-/ㄕ], “shirt.” To distinguish these sounds from the western ones, the tip of the tongue should be rolled up, touching the hard palate right behind the teeth. This movement should be gentle and will carry the sides of tongue up, shaping the tongue like a cupped hand.

Ri/ ㄖsounds like the “r” in “round.” Nonetheless, the lips do not need to be rounded when pronouncing ri/ㄖ.

When combined with various vowels, these consonants are marked as /t͡s/, /t͡sʰ/, /s/, /ʈ͡ʂ/, /ʈ͡ʂʰ/, /ʂ/ and /ɻ̩/ in IPA. When standing alone, after the initial sound, they become voiced—/t͡sz̩/, /t͡sʰz̩/, /sz̩/, /ʈ͡ʂz̩/, /ʈ͡ʂʰz̩/, /ʂz̩/ and /ɻ̩-z̩/–and ending with a shallow vowel sound, which is unmarked in Zhuyin, marked as “i” in pinyin, “y” in GR, and /ɨ/ in IPA.

In singing, keeping the voiced /z̩/ vibrate consistently can help carrying the sound. Zhao Yuanren had suggested to open the shallow vowel to a schwa, or to an “i” sound for 日. These adjustments need to be done with gentle touch so not to lose the natural sounds of the words.

Since Chinese is a syllabic language, each of these sounds can represent many different words/characters. Some of them are extremely common:

子, [zi3, ㄗˇ], “son,” “child”

詞, [ci2, ㄘˊ], “word combination,” “lyrics,” “ci poetry”

思, [si1, ㄙˉ], “to think,” “to miss”

絲, [si1, ㄙˉ], “silk,” “thread”

知, [zhi1, ㄓˉ], “to know,” “knowledge”

只, [zhi3, ㄓˇ], “only”

吃, [chi1, ㄔˉ], “to eat”

師, [shi1, ㄕˉ], “teacher,” “master,” “to learn”

失, [shi1, ㄕˉ], “to lose,” “to fail,” “lost,” “failure”

十, [shi2, ㄕˊ], “ten”

石, [shi2, ㄕˊ], “stone,” “rock”

時, [shi2, ㄕˊ], “time,” “hour,” “season”

日, [ri4, ㄖˋ], “sun,” “day”

__Voiceless consonants

With the exceptions of /m/, /n/, /l/ and /r/, all Chinese consonances are voiceless.[32] In European languages letters b-/p-, d-/t-, and g-/k typically represent pairs of voiced/voiceless sounds. In GR and pinyin, they are used to differentiate unaspirated and aspirated sounds.

•Letter [b-] in pinyin is marked /p/ in IPA—voiceless bilabial plosive, and ㄅin Zhuyin. It sounds like the “p” in “speak.”

•[d-,] /t/—voiceless denti-alveolar plosives, and ㄉ, as “t” in “study.”

•[g-,] /k/—voiceless velar plosive, and ㄐ, as “ch” in “school.”

__Initials and finals

In ancient Chinese lexicon, dúruò (讀若, sounds-as/reads-as [another word]) was used to indicate the pronunciation of words. By the third century, a new method fǎnqiē 反切 was developed to replace the direct-comparison method. It became the standard method used in Middle Chinese rhyme dictionaries.[33]

In fǎnqiē, the sound of each character would derive from two other characters: The initial/onset of the first character, and the final as well as the tone of the second. This dichotomic division (without considering the tone) is still adopted in the phonological study of modern Chinese. Nevertheless, each Chinese syllable can be further divided into smaller phonemes: C (consonant)-G (glide)-V (vowel)-X (coda).[34] The vowel, often considered the nucleus of the sound, and the coda are associated with the rime. Not all the units need to be present in the sound construction.

In singing, considerations should be given to all the sound units. The initial consonant (when present) must be clearly pronounced without interrupting the melodic line. Durations of glide, vowel, and coda affect not only the intelligibility but also the expressiveness of the lyrics.

__Glides, diphthongs and triphthongs

There are three glides in standard Chinese: /j/ ([y-] in pinyin and [ㄧ] in Zhuyin; sounding as “y” in “yellow”), /ɥ/ ([yu-, ㄩ], “u” in French “suis”), and /w/ ([w-, ㄨ], “w” in “word”).[35] They can be in the initial position when an initial consonant is not present; the medial position between the initial consonant and the main vowel, and the final positions.

In traditional Chinese singing, especially in Kunqǔ theater, the sound of each word is divided into head, belly, and tail.[36] After enunciating the head sound clearly, the voice should move smoothly, yet with fluctuations, through the belly and gradually round up the tail. The prenuclear glides, handled as the belly, are often elongated or sung with melodic embellishments. This is in total contrast of the western practice of deemphasizing the glides. While the traditional method can cause difficulties in understanding the texts, the western approach overstresses the main vowel and misses the characteristics of the language. Zhao Yuanren suggested a middle-of the road handling, allowing sufficient time and sound to establish the glide before moving on to the vowel.[37]

Common [GV] words include:

夜 [ye4, ㄧㄝˋ], “night”

亞 [ya3/ya4, ㄧㄚˇ / ㄧㄚˋ], “Asia”

血 [xue3, ㄒㄩㄝˇ], literary pronunciations of “blood.”[38]

月 [yue4,ㄩㄝˋ], “moon”

雪 [xue3, ㄒㄩㄝˇ], “snow”

花 [hua1, ㄏㄨㄚ], “flower(s)”

我 [wo3, ㄨㄛˇ], “Personal pronoun, I”

Similar considerations must also be given to closing diphthongs [VG] [-ai, -ei, -ao, -ou, ㄞ ㄟ ㄠ ㄡ] and triphthongs [GVG] [-uai, -uei, -iao, -iou, ㄨㄞ ㄨㄟ ㄧㄠ ㄧㄡ]. Frequently used words in these groups include:

[VG]

愛 [ai4, ㄞˋ], “love”

淚 [lei4, ㄌㄟˋ] : “tear(s)”

道 [dao4, ㄉㄠˋ], verb: “to say,” “to tell;” noun: “way,” “path”

偶 [ou3, ㄡˇ]: “couple/pair,” “even numbers,” or “by chance,” “accidentally”

豆 [dou4, ㄉㄡˋ]: “bean(s)”

頭 [tou2, ㄊㄡˊ]: “head”

[GVG]

外 [wai4, ㄨㄞˋ]: “outside,” “foreign”

微 [wei2, ㄨㄟˊ]: “gentle”

有[iou3, ㄧㄡˇ]: “to have”

友 [iou3, ㄧㄡˇ]: “friend(s)”

遙 [iao2, ㄧㄠˊ]: “distant,” “far”

教 [jiao4,ㄐㄧㄠˋ]: “to cause,” “to tell;” [jiao1,ㄐㄧㄠ]: “to teach”

__/n/ and /ŋ/ finals

The two nasal consonants /n/ and /ŋ/, marked as “N” in phonological studies, should always be pitched in singing. While /n/ can occur in the initial and final positions, in standard phonology the /ŋ/ only occurs in the ending position.

They can be free-standing, proceeded by neutral/shallow vowels. The only character with the pronunciation /ˀɤŋ55/ [eng1, ㄥ]— 鞥, meaning “horse rein,”—is a rare word. On the contrary, words with /ən55/ [en1, ㄣ] pronunciation, such as 恩 (“favor,” “grace,” “kindness,” etc.) or 嗯 (an interjectional utterance), frequently appear in lyrics.

When the nasal consonants take place immediately after an initial consonant, e. g. 門 [men2, ㄇㄣˊ], “door;” 崩 [beng1, ㄅㄥ], “burst” or “eruption,” or 風 [fen1, ㄈㄥ], “wind,” the same shallow vowels, marked “e” in pinyin and unmarked in Zhuyin, serve as linkages. The final/nasal consonants become the hierarchical phoneme.

The same hierarchy will be given to /n/ and /ŋ/ in [VN] or [CVN] words with /i, y, u/ vowels, such as:

因 [in1, ㄧㄣ]: “cause,” “reason”

應 [ing1, ㄧㄥ]: “should;” [ing4, ㄧㄥˋ]: “to respond”

雲 [yun2, ㄩㄣˊ]: “cloud(s)”

尋 [xun2, ㄒㄩㄣˊ]: “search”

文 /wən³⁵/ , [wen2, ㄨㄣˊ]: “script,” “language,” “literature”[39]

東 /tʊŋ55/, [dong1, ㄉㄨㄥ]: “east”[40]

桐 /tʰʊŋ35/, [tong2, ㄊㄨㄥˊ]: “paulownia”

On the other hand, in words with /-ɑn/ or /-ɑŋ/ finals, the main vowel /ɑ/ shares the stresses and the duration with the nasal consonants:

安 [an1, ㄢ]: “safe,” “peaceful”

晚 [wan3, ㄨㄢˇ]: “evening,” “late”

談 [tan2, ㄊㄢˊ]: “to discuss,” “to talk,” “to converse”

難 [nan2, ㄋㄢˊ]: “difficult,” [nan4, ㄋㄢˋ): “disaster”

山 [shan1, ㄕㄢ]: “mountain(s)”

千 [qian1,ㄑㄧㄢ]: “thousand(s)”

點 [dian3, ㄉㄧㄢˇ]: “point(s),” “dot(s),” “drops”

洋 [yang2, ㄧㄤˊ]: “ocean”

想 [xiang3,ㄒㄧㄤˇ]: “to think,” “to miss [someone/something]”

江 [jiang1,ㄐㄧㄤ]: “river”

黃 [huang2, ㄏㄨㄤˊ]: “yellow”

窗 [chuang1,ㄔㄨㄤ]: “window(s)”

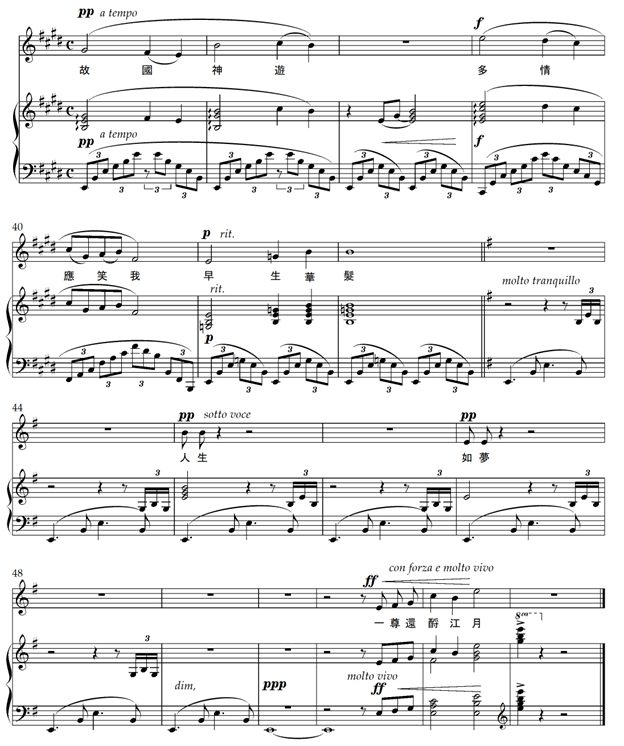

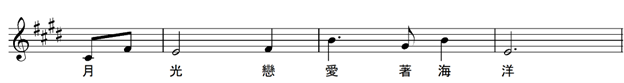

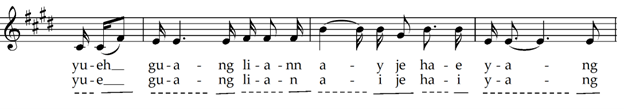

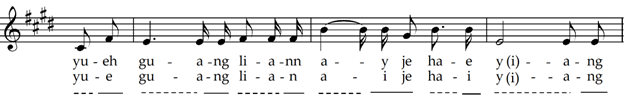

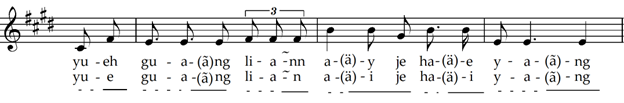

Zhao Yuanren quoted the phrase “月光戀愛著海洋” from 教我如何不想她 “How Can I Help [but] Thinking of You” to demonstrate proper handling of all the phonemes in each syllable/word.[41] In the following illustrations, the first line of transliteration is the original GR notation; the second one, pinyin. The dotted lines underneath the transliterations indicate the portion of the notes during which the words were not identifiable.

1. Following the western approach, quickly moving from glides to the main vowels and delaying the arrival of the final consonants.

2. Using the traditional practice, lingering on the glides and ending quickly with the vowel/finals.

3. A third method: evening out the duration of glides and vowel and adjusting the vowel sounds leading into the finals.

Judging by the lengths of the solid lines—the durations when the words are intelligible, the last execution would be the most appropriate one. The key fact is the clarification of the text—in context.

__Tones and tone sandhi

For non-native speakers, differentiating and pronouncing the Chinese tones are the most challenging part in learning the language. Even with the words set on fixed musical pitches, tonal inflections are still crucial in singing Chinese lyrics. From time to time, an unwritten slight might help to clarify the texts; from time to time, by lightening the sound, the interpreter can totally change the expression.

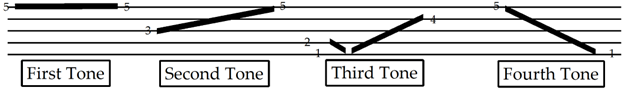

A “tone-letter” system devised by Zhao Yuanren and adopted by IPA can be helpful for musicians. As Zhao explained:

The total [speech] range is divided into four equal parts, thus making five points, numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, corresponding to the low, half-low, medium, half-high, high, respectively. . . .

As the intervals of speech-tones are only relative intervals, the range 1–5 is taken to represent only ordinary range of speech intonation, to include cases of moderate variation of logical expression, but not to include cases of extreme emotional expression. For purposes of tone drills, each step may be taken to be a whole tone, thus making the total range equal to an augmented fifth. This would make the successive pronunciation of a number of tones sound rather unmusical, which however is rather an advantage for phonetic purposes.[42]

In standard IPA, instead of tone letters, the tonemes are represented by numbers as shown in the following diagram. The first number for each tone indicates the onset pitch; the last number, the ending. For the third tone, the pitch quickly dips from 2 to 1 before rising to 4. Thus, 媽[ma1, ㄇㄚ], “mother,” will be marked as /ma55/; 麻[ma2, ㄇㄚˊ], “hemp” or “numb,” as /ma35/; 馬 [ma3, ㄇㄚˇ], “horse,” /ma²¹⁴/; and 罵 [ma4, ㄇㄚˋ], “to scold,” “to curse,”, /ma51/. The falling character of the fourth tone is comparable to grave accents in Italian: e. g. the Italian word fù (“was”) is a homonym of 父 [fu4, ㄈㄨˋ], “father.” The diacritical signs used in Zhuyin and pinyin, ˉ, ˊ, ˇ, ˋ, are derived from these graphic lines.

*The five lines here represent five whole-tone steps, not intervals of thirds as in a regular musical staff.

The tone of an individual word is often modified when combined with other word(s). Phonologically, this phenomenon is called “tone sandhi.” Unmarked in neither pinyin nor Zhuyin, tone sandhi must be learned through practical applications. It occurs mostly with the third-tone words.

Full third-tone pronunciations only happen when speaking individual words. When combined with first-tone, second tone and fourth tone words, the rising segment of the tone is often omitted, creating a “half-third tone.”

When two third-tone words are linked together, the first one will be pronounced in the second tone:

你好, “How are you” [ni3-hao3, ㄋㄧˇ ㄏㄠˇ], will be pronounced [ni2-hao3, ㄋㄧˊ ㄏㄠˇ]. 手指, “finger(s)” [shou3-zhi3, ㄕㄡˇ ㄓˇ], becomes [shou2zhi3, ㄕㄡˊ ㄓˇ]

In phrases with three consecutive third-tone words, the word grouping will determine the modification procedure:

處理好 [chu3-li3-hao3, ㄔㄨˇ ㄌㄧˇㄏㄠˇ] is a three-word phrase meaning “manage well.” The first two words form a verb-phrase, 處理 “manage,” modified by the adverb 好 “well.” This results in the first two words changing into the second tone. The natural (native) pronunciation of the phrase thus becomes [chuli2 hao3, ㄔㄨˊ ㄌㄧˊ ㄏㄠˇ].

In a phrase like 小老鼠 [xiao3-lao3-shu3, ㄒㄧㄠˇ ㄌㄠˇ ㄕㄨˇ], the first character, meaning “little,” is modifying the two-word noun “mouse.” Thus, the middle character will be pronounced in the second tone. The phrase will sound like [xiao3 lao2shu3, ㄒㄧㄠˇ ㄌㄠˊ ㄕㄨˇ].

Although there are endless phrasal combinations, the contents and the stresses are always determining factors of tone modification, which take place naturally to help with the flow of the language.

Two extremely common words 不 [bu4, ㄅㄨˋ], “no,” and 一 [yi1, ㄧ], “one,” follow special tone-change procedures:

不 changes to the second tone when followed by another fourth-tone word:

不見 [bu2jiang4, ㄅㄨˊ ㄐㄧㄢˋ]: “not seeing,” “disappear”

不負 [bu2fu4, ㄅㄨˊ ㄈㄨˋ]: “not to betray”

一 as a number or as the final character of a phrase will be pronounced in the first tone:

一零一 [yi1-ling2-yi1, ㄧ ㄌㄧㄥˊ ㄧ], “101”

唯一 [wei2-yi1, ㄨㄟˊ ㄧ], “only,” “unique”

一 is pronounced in the fourth tone after words in the first-, second- and third tones:

一天 [yi4tian1, ㄧˋ ㄊㄧㄢ]: “one day”

一直 [yi4zhi2, ㄧˋㄓˊ]: “straight ahead,” or “always,” “continuous”

一點 [yi4dian3, ㄧˋㄉㄧㄢˇ]: “a little”

It changes into the second tone when proceeding a fourth-tone word:

一定 [yi2ding4, ㄧˊ ㄉㄧㄥˋ]: “for sure,” “definitely”

In spoken Chinese, there is a neutral/fifth, and often neglected, tone. Its Chinese name 輕聲 [qing1sheng1, ㄑㄧㄥ ㄕㄥ], meaning “light sound,” reflects its phonological character perfectly. Unmarked in pinyin, it is marked with a staccato sign in Zhuyin “∙.”[43] With no fixed pitch level, neutral sounds take place at the end of phrases.

It is used in the character 們 [men, ˙ㄇㄣ], a suffix indicating plural form; 著 [zhe, ˙ㄓㄜ], when used as an aspect particle indicating the continuity of an action; 的 [de, ˙ㄉㄜ], possessive particle; and 得. [de, ˙ㄉㄜ], adverb.

Neutral tone is used in the second character of duplicated words, such as 謝謝 [xie4xie, ㄒㄧㄝˋ ˙ㄒㄧㄝ], “thank you”, and kinship terms, such as 爸爸 [ba4ba, ㄅㄚˋ ˙ㄅㄚ], “daddy,” 媽媽 [ma1ma, ㄇㄚ ˙ㄇㄚ], “mommy,” 爺爺 [ye2ye, ㄧㄝˊ ˙ㄧㄝ], “grandpa,” 奶奶 [nai3nai, ㄋㄞˇ ˙ㄋㄞ], “grandma,” etc.

In conversations, 不and 一, when occurring in the middle of three-character phrases, are often lightened, e. g. 是不是 [shi4bushi4, ㄕˋ ˙ㄅㄨ ㄕˋ], “Isn’t it?”, 想一想 [xiang3yixiang3, ㄒㄧㄤˇ ˙ㄧ ㄒㄧㄤˇ], “think about it.”

While the application of the neutral tone is not as crucial in phonological procedure, the appreciation of such words/phrases can have greatly enhance musical interpretation.

__Érhuà

In northern dialects, especially colloquial Beijing dialect, a vowelized “r” /ɚ/ is often attached to the end of words as a diminutive suffix. This procedure is name by its sound as 兒化 /ˀɤɻ³⁵ xwä⁵¹/ [er2hua4, ㄦˊㄏㄨㄚˋ]. The rhotacism can result in: 1) elimination or nasalization of final consonants, or 2) modification of nuclear vowel sounds. Similar sounds can be found in American English such as “-er” in “butter,” “-ir-” in “shirt,” and “-ear” in “tear.

Commonly used in daily conversations, erhua also appears in literary works as indications of intimacy. Liu Bannong 劉半農 included two erhua phrases in “How Can I Help [but] Thinking of You:”

. . . . 水底魚兒慢慢游。

[Little] fish swim leisurely down below.

. . . . 啊! 西天還有些兒殘霞,

Ah! [Little bit of] twilight glows are still lingering on the western sky.

Since these “兒” characters are part of the verse structure, they are most often set to fixed pitches and note values in musical settings. It will be appropriate to release the sound gently to reflect the phonological character as well as the expressions.

So, how should Li Qingzhoa’s “守著窗兒,獨自怎生得黑!” be handled?

[1] In addition to the Han languages, there were hundreds of minority languages.

[2] Sinitic_languages_Wiki, Varieties_of_Chinese_Wiki

[3] Chao Yuen Ren, Xin shi ge ji新詩歌集, revised edition, (Taipei, Taiwan shang wu yin shu gua 臺灣商務印書館, 1960), 9.

[4] The “Preparatory Commission for the Unification of the National Language” was created in 1919. It was restructured and renamed as the Preparatory Committee in 1928.

National_Languages_Committee_Wiki

[5]Early in the development of language unification, a system combining both northern and southern mandarins (Wu) was propositioned. This “old national pronunciation” was closer to Middle Chinese, influenced by the rhyme dictionary Zhongyuan Yinyun 中原音韻. It retained the checked/entering tone.

Old_National_Pronunciation_Wiki

A pronunciation dictionary Guoyu Cidian國音字典, using Zhuying transliterations 注音符號, was published in 1920.

[6] The character, when used as a verb, meaning “return,” is also pronounced [huan2].

[7] Xin shi ge ji, 54.

[8] In pinyin or Romanization, the pronunciation is marked as [le]. The schwa IPA is used here for clarification.

[9] 得_en.wiktionary.org

[10] 的_en.wiktionary.org

[11] 和_en.wiktionary.org

[12] Colloquially, it could be pronounced in the second tone, [huó2].

[13] 更_en.wiktionary.org

[14]Although the pinyin for 更 is spelled “geng,” the IPA symbol /k/ reflects the voiceless consonant more appropriately. The vowel /ɤ/ is further back from /ə/. See further explanations below.

[15] 曲_en.wiktionary.org. The sound of [u] in pinyin is similar to “ü” in German.

[16] Standard_Chinese_phonology_Wiki, Help:IPA/Mandarin_Wiki

[17] Romanization_of_Chinese_Wiki

[18] Wade-Giles_Wiki

[19] Yale_romanization_of_Mandarin_Wiki. The Yale system is widely used in teaching Cantonese. It is also the standard romanization of Korean.

[20] 駁中國用萬國新語説_zh.wikisource.org

[21] Katakana_Wiki, Seal_script_Wiki

[22] Phonetic_symbols_by_Zhang_Taiyan_commons.wikimedia.org

[23] Aka Wu Jingheng 吳敬恆.

[24] 注音符號_Wiki, Bopomofo_Wiki

[25] Gwoyeu_Romatzyh_Wiki, 國語羅馬字_zh.m.wikipedia.org, Spelling_in_Gwoyeu_Romatzyh_Wiki

[26] Xin shi ge ji, 56-59.

[27] Further modifications will apply to certain letter/vowel combinations.

[28] Mandarin Primer and Grammar of Spoken Chinese

[29] Shaan-Gan-Ning_Border_Region_Wiki

[30] John DeFrancis, The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, paperback. (Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1986), 254.

[31] The basic spelling of these consonants in GR are: [jy-, chy-, shy-,ry-, tzy, tsy, sy.] In GR, the [j-, ch-, and sh- ] initials, when combined with “I,” become the equivalences of [ji-, qi-, xi-] in pinyin, and ㄐ ㄑ ㄒin Zhuyin.

[32] One of the major phonological changes between the Late Middle and modern Chinese was the devoicing of consonances. goldfishodyssey.com/2021/10/24/chinese-poetry-xiii-turning-point/

[33] Fanqie_Wiki

[34] The X (code) can be a non-vocalic consonant or a glide.

[35] The Zhuyin symbols are used for the allophonic vowels: /i/, /y/, and /u/. The /ɥ/ glide can be considered as a lighter and shorter /y/, the German “ü.”

[36] 字頭, 字腹, and 字尾.

[37] Xin shi ge ji, 55.

[38] The colloquial/spoken pronunciation of 血 is [xie3, ㄒㄧㄝˇ]

[39] In ㄨㄣ(/u/+/n/) combination, as the tongue moves slightly inward, the glide turns into a schwa, which is spelt as an “e” in pinyin and unmarked in Zhuyin.

[40] The phonological procedure of theㄨㄥ (/u/+/ŋ/) combinations begins with the /w/ glide, which opens to an /ʊ/ vowel before reaching the final. Thus, it is spelt with as [-ong] in pinyin

[41] The word 光 was original set to e-g-sharp. Zhao omitted the second note for the convenience of discussion. In the GR transliteration, the “h” in [yueh] and the second “n” in [liann] are tone indicators—fourth tone here. [Ay] was the fourth tone modified spelling of the basic [ai] sound; [hae,] the third of [hai.]

[42] Tone_letter_Wiki

Y. R. Chao, “ə sistim əv ‘toun-letəz’” [“A System of ‘Tone-Letters”], Le Maître Phonétique Vol. 8 (45), No. 30 (avril-juin, 1930), 25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44704341

[43] The staccato sign appears in front of the symbols in Zhuyin.