I was not even four when the movie Liang Shanbo yu Zu Yingtai (English title: The Love Eterne) opened. Romeo and Juliet met The Sound of Music, it was an instant box office sensation. There was no video recording and no cable-on-demand. Online streaming would have been totally unthinkable. Many people saw the film in theaters repeatedly. The sound track was played on the radio all day long.

Zu was from a wealthy family. Having convinced her father, she disguised as a man to pursuit scholarship. (Women were discouraged from intellectual pursuits.) Liang was a poor fellow student who befriended her not knowing her true identity. Three years later she was summoned home to marry a wealthy man. By the time he realized she was a woman, it was too late. Heartbroken, he became ill and died. She passed by the grave on her way to the groom’s home. A thunder split the grave open. She jumped in without hesitation. According to the legend they emerged as a pair of butterflies. In Western references, they were often called the “butterfly lovers.” Their story inspired generations of artists and musicians. (The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto is one of the most important Chinese orchestral works of the twentieth century.)

In 1963 Shaw Brothers Studio, the largest film production company in Hong Kong, adapted this tragic story in the style of Hungmei opera. Originated from folk tunes sung by women while picking tea leaves, Hungmei is less formal than Beijing opera. Male characters are often played by female actresses. Because of its congenial melodies, its popularity grew rapidly in the mid-twentieth century. In Shaw Brothers’ production, the theme songs were accompanied by western orchestra. Elaborated costumes and sets strengthened the dramatic effects.

None of these things mattered to a three-year-old. It, nevertheless, influenced me in many ways:

I saw the film a few times. When the lovers were forced to be apart, the music became more and more agitated. The audience sobbed along with the actors. I experienced the impactful power of the big screen first hand.

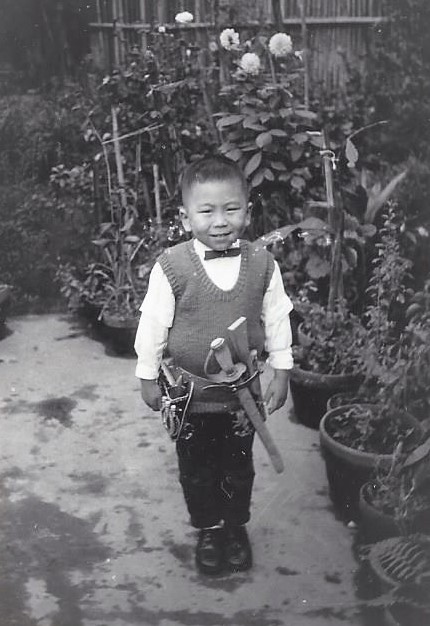

Not fully understand the lyrics, I was able to pick up the tune and sing along. I could also mimic the theatrical gestures of the actors. Too young to be intimidated and too young to know the importance of modesty, I was only too eager to show off my new tricks to visitors: neighbors, relatives and family friends alike. Soon I would begin taking dance classes.

The actress who played Liang Shanbo in pants role, previously an unknown, gained overnight popularity. When she visited Taiwan later, fans lined up the streets throwing flowers and gifts to her black town car. Military guards were sent to maintain order. I saw the photos on newspaper. To me, she was almost as beautiful as brides—only brides would ride in black town car and only brides would be surrounded by flowers. I wanted to be a bride. Only years later, I realized that being a diva was a much better gig.

Many things in the movie puzzled me. The most troublesome fact was that a girl had to pretend to be a man just to go to school. Going to school was a good thing. Not letting girls go to school was bad. If she didn’t have to dress like a man, she might not have to die so tragically. A feminist was born.

Two years later, The Sound of Music arrived in Taiwan. Released under the Chinese title 真善美 (Truth, Goodness and Beauty), it stirred up another box office storm. My family joined the crowd at the theater multiple times. My dance teacher choreographed a piece based on a medley of the sound track. Unlike The Love Eterne, this movie brought us nothing but happiness.