Chance Encounter 偶然

Xu Zhimo 徐志摩

我是天空裡的一片雲

[wo3 shi4 tian1 kong1 li3 di5 yi2 pian4 yun2]

ㄨㄛˇ ㄕˋ ㄊㄧㄢˉ ㄎㄨㄥˉ ㄌㄧˇ ㄉㄧ˙ ㄧˊㄆㄧㄢˋ ㄩㄣˊ

I am a cloud in the sky,

偶然投影在你的波心[1]

[o3 ran2 tou2 ying3 zai4 ni3 di5 bo1 xin1]

ㄡˇ ㄖㄢˊ ㄊㄡˊ ㄧㄥˇ ㄗㄞˋ ㄋㄧˇ ㄉㄧ˙ ㄅㄛˉ ㄒㄧㄣˉ

By chance reflecting on your rippling heart.

你不必訝異

[ni3 bu2 bi4 ya4 yi4]

ㄋㄧˇ ㄅㄨˊ ㄅㄧˋ ㄧㄚˋ ㄧˋ

You need not be surprised,

更無需歡心

[geng4 wu2 xu2 huan1 xin1]

ㄍㄥˋ ㄨˊ ㄒㄩˉ ㄏㄨㄢˉ ㄒㄧㄣˉ

Nor should you be overjoyed.

在轉瞬間消滅了蹤影.

[zai4 zhuan3 shun4 jian1 xiao1 mie4 liao3 zon1 ying3]

ㄗㄞˋ ㄓㄨㄢˇ ㄕㄨㄣˋ ㄐㄧㄢˉ ㄒㄧㄠˉ ㄇㄧㄝˋ ㄌㄧㄠˇ ㄗㄨㄥˉ ㄧㄥˇ

In the blink of an eye, I could dissipate without a trace.

***********

你我相逢在黑夜的海上,

[ni3 wo3 xian1 feng2 zai4 hei1 ye4 di5 hai3 sheng4]

ㄋㄧˇ ㄨㄛˇ ㄒㄧㄤˉ ㄈㄥˊ ㄗㄞˋ ㄏㄟˉ ㄧㄝˋ ㄉㄧ˙ㄏㄞˇ ㄕㄤˋ

You and I met each other in the darkness of the night sea.

你有你的,我有我的,方向;

[ni3 yo3 ni3 di5 wo3 yo3 wo3 di5 fang1 xian4]

ㄋㄧˇ ㄧㄡˇ ㄋㄧˇ ㄉㄧ˙ ㄨㄛˇ ㄧㄡˇ ㄨㄛˇ ㄉㄧ˙ ㄈㄤˉ ㄒㄧㄤˋ

You had yours; I had mine; directions

你記得也好,

[ni3 ji4 de2 ye3 hao3]

ㄋㄧˇ ㄐㄧˋ ㄉㄜˊ ㄧㄝˇ ㄏㄠˇ

It is fine, should you remember. . .

最好你忘掉,

[zui4 hao3 ni3 wang4 diao4]

ㄗㄨㄟˋ ㄏㄠˇ ㄋㄧˇ ㄨㄤˋ ㄉㄧㄠˋ

Better that you forget:

在這交會時互放的光亮!

[zai4 zhe4 jiao1 hui4 shi2 hu4 fang4 di5 guang1 liang4]

ㄗㄞˋ ㄓㄜˋ ㄐㄧㄠˉ ㄏㄨㄟˋ ㄕˊ ㄏㄨˋ ㄈㄤˋ ㄉㄧ˙ ㄍㄨㄤˉ ㄌㄧㄤˋ

The radiance we projected upon each other during our encounter.

With its picturesque narration and romantic sentiment, Xu Zhimo’s “Chance Encounter 偶然” has, throughout the decades since its creation, been a popular choice of lyrics for classical composers and singer-songwriters alike. The following discussion will focus on the art-song setting of 1936 by Weining Lee 李惟寧. For details on the poem, please refer to: goldfishodyssey.com/2022/01/04/chinese-poetry-xvii-chance-encounter-偶然/

__ Lee Weining李惟寧 (1906-1985)[2]

Lee Weining 李惟寧 was born into a prominent family in Ningyuan Prefecture 寧遠府 of Sichuan Province.[3] In the early 1920, he entered Tsinghua College, a program funded with Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, preparing students for overseas study in the United States.[4] Instead of focusing on his academic works, Lee was attracted to the music activities around him. He learned to play to the violin, trumpet, trombone and French horn, and began taking piano lessons. His poor attendance and failing grades eventually led to his expulsion from the school in 1928. Briefly, while making a living by teaching English and piano, he became active in local musical groups and appeared in performances—partially to raise fund for studying abroad.

Lee won the Sino-French Cultural Foundation Scholarship and obtained a tuition waiver at Schola Cantorium in Paris. For two years (1930?-1931), he studied Piano under Léon Kartun, and Lazare Levy; counterpoint under Bertlin; and composition under Vincent d’Indy.[5] After the death of d’Indy, he left for Vienna. There, he attended the Akademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst, studying composition with Franz Schmidt and Joseph Marx. After Marx’s retirement, he studied counterpoint and compositions with Karl Weigl and took private piano lessons from Frau Prof. Leonie Gombrich.

In 1933, Lee passed the Staatsprüfung (State Exam) with honor and married Elisabeth Heinrich on June 11.[6] He began working at the Konsularakademie. On July 16, 1934, eight compositions of his were broadcast on Radio-Verkehrs AG (RAVAG). The performers were Erika Rokyta, soprano; Bertha Jahn-Beer, piano solo; and the composer also at the piano.[7]

An article in the July 13 issue of Radio-Wien introduced Lee as a young Chinese composer from an illustrated literary family in a province near the headwater of the Yangtze River. It explained how his years in Tsinghua, though led to conflicts between him and his father, paved the way for his musical life. While accredited his mentors, the author also praised Lee for his ability to acculture to the essence of European music in his compositions.[8]

A detailed playlist was provided in the same issue of the weekly, translated and amended here in English:[9]

__Part 1:

a) “Chance Encounter,” Xu Zhimo;

b) “Laments in Exile,” Li Yu;

c) “The Crane,” [Su Shi]

(Rokyta)

“Variations and Fugue on an Original Theme” for piano

(Bertha Jahn-Beer)

__Part 2:

a) “Song of the Fisher Boy,” Schiller, [Chinese translation by] Guo Moro;

b) “Deep Night,” Lee Wei’e

c) “The Fisherman,” Zhang Zhihe

d) “Parables of the Pond,” Bai Letian[10]

(Rokyta)

Six of the seven songs included in Lee’s solo collection Du chang ge ji 獨唱歌集 of 1937 appeared in this playlist. The last piece “Chi sheng yu xing 池上寓興” [Parables of the Pond] later became a four-part chorus work.[11]

The reviewer at Der Wiener Tag gave high praise to the only instrumental piece—the “Variations and Fuge”—on the program: “. . . one would not sense at all that it was a foreigner at work here. This keyboard piece was fully tailored to the emotional capacity of the instrument. The delicate, transparent keyboard work that Lee wrote, reminds one of his models such as François Couperin and d’Indy, to which romantic piano works of Schubert, Mendelssohn und Schumann should also be added.” The same reviewer also commented on the inner European spirit of Lee’s vocal works underneath a folk-song-like appearance.[12]

Lee Weining chose Guo Moro’s translation of Friedrich Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell as his source of lyrics.[13] In his 1981 article, “Im Reich der Töne fließen Jangtse und Donau zusammen” (In the Realm of Sounds, Yangtze and Donau Flowing Together), Liao Naixiong 廖乃雄 compared Lee’s “Lied des Fischerknaben” with the reverse efforts, translating Chinese verses into German lyrics, in Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, Ernst Tochs’ Chinesische Flöte, and Anton Webern’s “Die geheimnisvolle Flöte.”[14]

Having achieved a certain level of success in assimilating to European culture and life in the early 1930s, Lee returned to China in autumn of 1934. He taught piano and theory briefly at the Central University of Nanking, then joined the faculty of the National Conservatory of Music, Shanghai in October of 1935. After the death of Xiao Yomei in January of 1941, Lee became the interim Director. When Wang Jingwei’s puppet state of the Japanese occupiers (汪精衛偽政府) took over the Conservatory in June of 1942, Lee was appointed the Director.[15]

In addition to teaching theory, composition, and piano after returning to China, Lee Weining should be credited to introducing Western repertoire to the Chinese audience as a solo pianist, an administrator, and a conductor. To fully appreciate the significance of his activities, one must first understand the cultural and social divisions between Westerners and natives in Shanghai in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Under unequal treaties, sections of Shanghai became foreign concessions. In 1854, a group of businessmen founded “Shanghai Municipal Council 工部局”—a self-governing body—to manage the daily function within the confines of the International Settlement.[16] While the Westerners benefited from the extraterritorial rights, Chinese locals were prevented from entering public venues and, consequentially, attending public events.

In 1879, the “Shanghai Public Band 工部局樂隊” was formed to provide entertainment and ceremonial music for audience from the concessions. In 1922, the band was renamed “Shanghai Municipal Orchestra.”[17] Under the increasing public pressure, the SMO finally opened its door to the Chinese community in 1925. Two years later, Tan Shuzhen 譚抒真, a violinist, became the first Chinese musician in the orchestra.[18] In 1930, SMO performed the work of a Chinese composer—In Memoriam by Huang Zi—for the first time.[19]

Throughout the 1930s, the involvement of Chinese musicians in SMO grew gradually. Huang Zi was invited to join the Orchestra and Band Committee of the Municipal Council in 1931. After his death, Lee Weining served as a committee member from 1938 to 1942. Beginning with the appearance of Ma Sicong 馬思聰, a 17-year-old violinist, in 1929, Chinese soloists, both instrumentalists and vocalists, were featured in the SMO concerts.[20] On February 21, 1937, Lee Weining performed Mozart, D minor Piano Concerto (K. 466) using his own cadenza in the third movement. Also included in the same program were “Overture” to Marriage of Figaro, Cello Concerto by Luigi Boccherini, and the New World Symphony by Dvorak.[21] By its programming of standard Western repertoire, the SMO concerts inspired many young musicians and stimulated the development of modern Chinese music.[22]

Lee’s brief biography in the Curriculum Catalogue of Boston Conservatory of Music indicated that he “organized and conducted [the] first Symphony Orchestra in Shanghai.” This “first Symphony Orchestra” in the statement was not SMO. Instead, it was an all-Chinese orchestra, Shanghai Orchestra 上海管弦樂團, founded by Huang Zi and Tan Xiaolin 譚小麟 on November 1, 1935. Wu Bochao 吳伯超 and Lee Weining were named the chief and deputy conductors.

On May 15, 1937, Lee conducted Shanghai Orchestra’s first public performance at Ba Xian Qiao YMCA 八仙橋青年會.[23] In addition to works by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Mendelssohn, the program also included two songs— “Yi wangmu 憶亡母” [Remembering late mother] by Lee and “Ständchen” by Schubert—sung by bass baritone Yi-Kwei Sze 斯藝桂.[24] The performance seemed to have been well-received.[25]

Between April and May of 1937, three of Lee’s vocal collections were published as part of the National Music Academy Series by the Commercial Press: Shuqing Hechangqu 抒情合唱曲 contains lyrical choral works with traditional texts. Du chang ge ji 獨唱歌集 was his first solo collection of seven pieces. Aiquo Geji: Junge 愛國歌集: 軍歌 were patriotic and military songs. In June the same year, Lee orchestrated the Nationalist Party Song, recently adopted as the National Anthem.

Acting against the Zeitgeist and the spirit of his patriotic compositions, Lee Weining remained in Shanghai after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out and collaborated with the Japanese occupiers. As the war ended, he was removed from his administrative position at the Conservatory in 1946 but continued teaching there for another year. He moved to the United States in 1947 and taught at Boston Conservatory of Music until his retirement in 1976.

Publicity materials of various events indicated that Lee Weining began writing piano works before studying abroad.[26] It was also clear that he had written chamber music as well as orchestral works. Unlike his songs and choral compositions, which were preserved and appeared in concerts, his instrumental works—most of them well-received by critics—seemed to have been lost. His avid creative works as a composer and performer ended abruptly with his move to America.

— “Ou ran”

Lee Weining’s setting of Xu Zhimo’s most beloved work was believed to have been set almost immediately after the publication of the poem in May of 1926. The source of this date seemed to have been an anecdotal account in Xishu Changge Xing 西蜀長歌行 by Guo Hongqiao 顧鴻喬.[27] Lee was twenty years old and enrolled at Qinghua in 1926. As enthusiastic as he was about learning western music, he might not have acquired the skills needed to compose an art song.

“Ou-ran 偶然” was the last of the forty songs in Volume 2 of Centennial Chinese Art Song Collection (2020), published by Shanghai Conservatory Press.[28] There, 1936 was listed as the compositional date. Nonetheless, since the song was included in Lee’s 1934 RAVAG recital, it would have been written prior to July 1934.

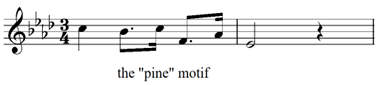

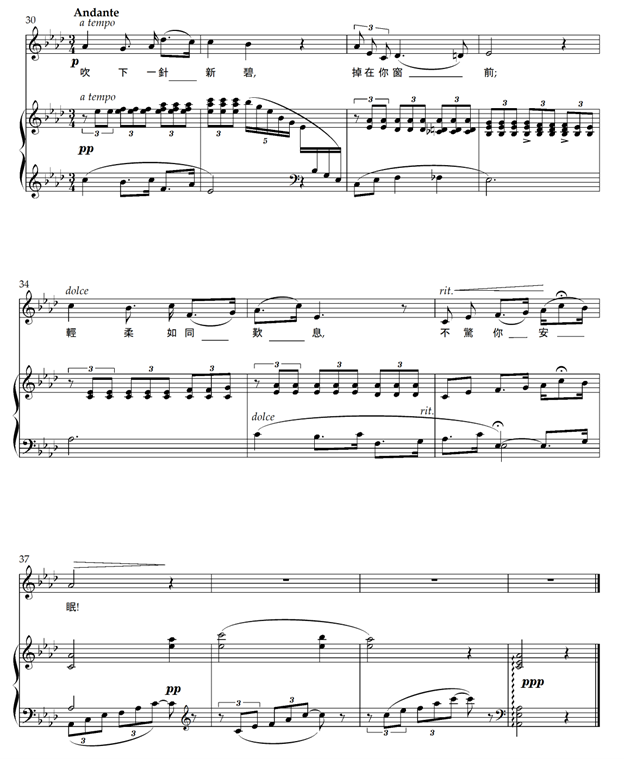

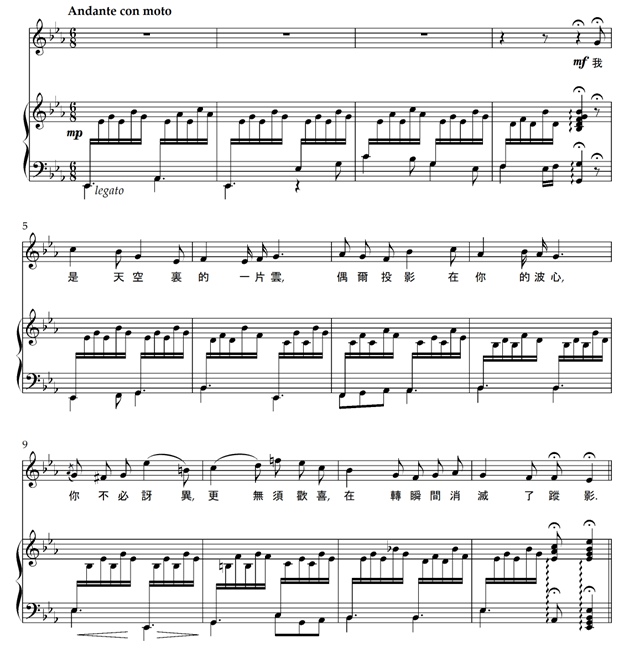

Corresponding to the contemporary nature of the poem, Lee utilized western tonality and style for his setting. The song is in simple ternary form with a brief piano introduction. The text is set syllabically throughout. The opening motive first appears in the bass line of the introduction. The first stanza is set in E-flat major with smoothly arpeggiated accompaniment.

In the second section, quick triplets in the vocal part and the repeating chords in the piano part invoke a sense of uneasiness which is enhanced by the C-minor tonality. The third section is a complete recapitulation of the first.

Lee drew upon a few musical gestures to enhance the emotions of the words. In mm. 9 and 10, there is a juxtaposition of E-flat major and C minor to highlight verses 3 and 4—”你不必訝異, 更無需歡心 You need not be surprised, nor should you be overjoyed.” The so-far smooth vocal line is interrupted by grace notes, chromatic steps, large interval, portamenti and widened range. The excitement is, nevertheless, short-lived.

The musical reaches a climax in m. 17 with a g2 in the voice. The text reads: “你記得也好, . . . It’s fine, should you remember. . ..” Then, as the lyrics makes a dramatic turn at “最好你忘掉, Better that you forget,” the vocal line stops abruptly. The piano, with accented chords, repeats the last three notes/words. The second section ends with a cadence in the dominant B-flat major, giving way to the reiteration of the first stanza.

Lee Weining’s “Ou ran” is uncomplicated yet not oversimplified. The singer needs to find the right tempo which allows clear and smooth delivery of the word. The occasional leaps in the vocal line should sound effortless. The pianist should pay attention to the counter-melody in the bass line which pairs with the voice throughout the piece. The key musical moments in each section will require the collaboration of both performers.

[1] The literary pronunciation [ㄉㄧˋ, di4] is applied here for the word 的. To maintain the vernacular style of the poem, it should be sung naturally without strenuousness.

[2] In western documents, Lee’s given name is sometimes hyphenated (Wei-Ning) or with two separated syllables without hyphenation (Wei Ning). His family name appears both as “Li” and/or “Lee.”

Lee’s grandfather Lee Liyuan 李立元 was the minister of Ningyuan Prefecture at the time of his birth.

[3] Geni, a genealogical site, listed Chengdu, Sichuan as his birthplace.

https://www.geni.com/people/Lee-Wei-Ning/6000000010110054635

[4]. Exact dates of Lee’s activities and works varied from source to source. Discussions in this article are based largely on the following sources:

__ Gerd Kaminski, “‘Es ließen sich endlich seine Majestät belieben, die Lieblichkeit der europäischen Musik zu verkosten’. China und Österreich im Reich der Musik,” China-Report, Nrs. 163-164/2013, Österreichisches Institut für China-und Südostasienforshucng, 15-16.

https://www.icsoa.at/publikationen/china-report/report2013/

__Boston Conservatory of Music Curricula Catalogs (1948-1949), 9

https://archive.org/details/catalogue1948bost/page/9/mode/1up Accessed June 30, 2024. This is a summary of Lee’s training and experiences prior to joining the faculty at BCM. It is possibly based on Lee’s own narration.

__ Wei Jinsheng 韋金生, “Introduction of Composer-Pianist Lee Weining 作曲家、鋼琴家李惟寧介绍,” appeared in three parts on Dagongbao 大公報 from 1937, March 31 to April 2.

https://archive.org/details/dagongbao-shanghai-1937.03.31/page/n13/mode/1up

https://archive.org/details/dagongbao-shanghai-1937.04.01/page/n13/mode/1up

https://archive.org/details/dagongbao-shanghai-1937.04.02/page/n13/mode/1up Accessed on June 30, 2024

__ Liu Sheng 留生, “From ‘Preparatory Student of Tsinghua College for Oversea Study in the US’ to ‘Director of Theory and Composition Group in National Institute of Music’: The Life Trajectory of Musician Li Weining in His Youth (1923-1937)從‘清華留美預備生’到‘國立音專理論作曲组主任’,” Yinyue tansuo 音樂探索, November 13, 2023.

https://m.fx361.com/news/2023/1113/23075901.html Accessed June 29, 2024.

__https://www.icsoa.at/publikationen/china-report/report2013/

__Kong Hongyu 官宏宇, “Lee Weining’s European and Ameircan Years 李惟寧的歐美歲月,” Journal of the Central Conservatory of Music 中央音樂學報, 2023, No. 2: 101-117. This article in Chinese provides images of several original documents.

[5] Boston Conservatory of Music Curricula Catalogs, Ibid.

[6] China-Report, Ibid. Frau Gombrich was the maid of honor at his wedding.

[7] Radio-Wien, Vol. 10, No. 42 (July 13, 1934): 17.

https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=raw&datum=19340713&seite=19&zoom=33

[8] Ibid., 2.

https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=raw&datum=19340713&seite=4&zoom=33

[9] Ibid., 17. The Chinese titles and lyrists of the songs are: a)《偶然》, 徐志摩; 《春花秋月》, 李煜 (李後主); 《鶴歌》, 蘇軾; 《渔歌》, 席勒詩, 郭沫若譯; 《深夜》, 李惟峨; 《渔父》, 張志和; 《池上寓興》, 白樂天. Eric Gombrich provided the German translation of the Chinese lyrics.

[10] A direct translation of the German title “Die Parabel vom See“ should have been “The Parable of the Lake.” Nevertheless, 池上 [chi shang] in the original Chinese title means “on the pond.”

[11] The seventh work in Lee’s 1937 collection was “Nian shanzhong ke 念山中客” [Thinking of a friend who lives in the mountains] with words by Wei Yingwu 韋應物 of the Tang Dynasty.

[12] Der Wiener Tag, July 17, 1934, page 8:

„Gestern im Radio/Kompositionestunde Lee-Wei-Ning“

Ein junger Chinesischer Komponist, Herr Lee-Wei-Ning, Stipendist der „Schola cantorum“ in Paris und Schüler von Vincent d‘Indy, Joseph Marx und Karl Weigl, kam gestern im Radio mit eigenen Werken zu Wort. Tiefe Proben seines Schaffens, ein Variationen wert für Klavier und eine Reihe Lieder, zeugten von der großen Einfühlungsgabe der heutigen Chinesen in die abendländische Musik.

Bei den von Berta Jahn-Beer virtuos gespielten „Variationen und Fuge über ein eigenes Thema“ hat man überhaupt nicht des Gefühl, daß ein exotischer Fremdling hier am Werke war. Der Klaviersatz ist ganz den Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten des Instruments angepaßt. Der locker, durchsichtige Klaviersatz, den Lee-Wei-Ning schreibt, erinnert an Vorbilder wie François Couperin und d‘Indy, denen aber auch die romantischen Klavierstücke von Schubert, Mendelssohn und Schumann hinzuzuzählen sein dürften.

Stärker bricht das exotische Empfinden in den von tiefem Ausdruck erfüllten Liedern durch, die Erika Rokyta sang. Hier begegnen wir einem eigentümlichen Nebeneinander von freien Rhapsodischen, fast möchte man sagen: rezitativischen Wendungen, ariosen Clementen, imitatorisch gehaltenen Partien und—so merkwürdig es fliegen mag—einem volksliedartigen Einschlag in europäischem Sinne. Lästerer trat sehr auffällig in der „Parabel vom See“ nach Worten von Pe-Lo-Tien hervor.

[13] Lee was not the first composer to set a translated text. In 1926, Zhao Yuanren excerpted Gaston’s drinking song from Liu Bannong’s translation of Alexandre Dumas fils’ The Lady of the Camellias for his musical setting. Xin shi ge ji 新詩歌集 [New Poetry Songbook], Shanghai, 1928; revised edition, Taipei, 1960: 20-24, and 64.

[14] Liao Naixiong, “Im Reich der Töne fließen Jangtse und Donau zusammen,” China-Report, Nr 60, 1981, 31. http://oegcf.com/oesterreich-china-publikationen-china-report-archiv.php

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wang_Jingwei_regime

[16] The International Settlement was led by the British and American settlements.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanghai_International_Settlement

French concession, located south of the British settlement, was operated independently by the French authority. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanghai_French_Concession

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanghai_Symphony_Orchestra

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tan_Shuzhen

[19] Hon-Lun Yang, “From Colonial Modernity to Global Identity: The Shanghai Municipal Orchestra.” In China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception, edited by Hon-Lun Yang and Michael Saffle, 49–64. University of Michigan Press, 2017.

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1qv5n9n.6.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Liu Sheng, “The Life Trajectory of Musician Li Weining in His Youth.”

[22] One of the most significant events of the SMO was the Chinese premiere of the Nineth Symphony of Beethoven on April 15, 1936. “Ode to Joy” in the final movement was sung by choruses from Chinese, German, Russian, and other Western communities.

[23] Shen Bao 申報, May 10, 1937, page 13.

https://archive.org/details/shenbao-1937.05-120/page/n12

[24] “Yi wangmu” was written in the autumn of 1936. The complete program cited by Liu Sheng from Ta-lu Bao 大陸報 (The China Press), May 15, 1937, included: “Overture” to Don Giovanni, Mozart; The First Symphony, Beethoven; “Fingalshöhle,” Mendelssohn; “Turkish March” from The Ruins of Athens, Beethoven; and The Nineth Symphony, Haydn.

[25] Liu Sheng, Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Guo Hongqiao 顧鴻喬, Xishu Changge Xing 西蜀長歌行, Xiangjiang ke xue chu ban she香江科学出版社, Hongkong, 2021,cited by Zhang Jiazheng 張家正 in “Chengdu ren wu: Li Weininf 成都人物: 李惟寧 (2),” https://www.78621.org/chengdourenwuliweining-3/ The storytelling reminds one of the “Schubert-wrote-on-napkins” legend.

[28] Zhongkou Yishu Gequ Bai Nian Quji 中國藝術歌曲百年曲集, Volume 2, “Fang Xing Wei Ai 方興未艾,” Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press, Shanghai, 2020.