__ Listening to the Rain 聽雨

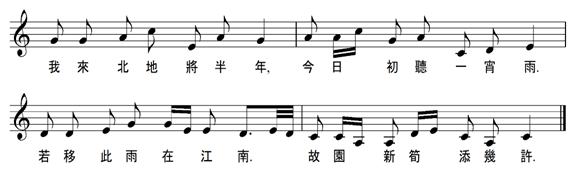

我來北地將半年

It has been almost half a year since my arriving in the northern land.

[wo3 lai2 bei3di4 jiang1 ban4 nian2]

ㄨㄛˇ ㄌㄞˊ ㄅㄟˇ ㄉㄧˋ ㄐㄧㄤ ㄅㄢˋ ㄋㄧㄢˊ

今日初聽一宵雨

Today, for the first time, I heard the rain throughout the night.

[jin1 ri4 chu1 ting1 yi4 xiao1 yu3]

ㄐㄧㄣ ㄖˋ ㄔㄨ ㄊㄧㄥ ㄧˋ ㄒㄧㄠ ㄩˇ

若移此雨在江南

If we move this rain south of the River,[1]

[ruo4 yi2 ci3 yu3 zai4 jiang1 nan2]

ㄖㄨㄛˋ ㄧˊ ㄘˇ ㄩˇ ㄗㄞˋ ㄐㄧㄤ ㄋㄢˊ

故園新筍添幾許

Our old orchard would have had a few more new bamboo shoots.

[gu4 yuan2 xin1 sun3 tian1 ji3 xu3]

ㄍㄨˋ ㄩㄢˊ ㄒㄧㄣ ㄙㄨㄣˇ ㄊㄧㄢ ㄐㄧˇ ㄒㄩˇ

__March 24, 1918, Liu Bannong

A proponent of new literature, Liu Bannong would occasionally return to the traditional poetic styles in his works. “Ting yü 聽雨” [Listening to the rain] from the Upper part (上卷) of Yangbian Ji 揚鞭集 (1926) was one of these poems.

At the first glance, the poem seems to be a typical seven-character jueju 七言絕句.[2] The detailed structure, on the other hand, revels characters of modern language. In traditional seven-word jueju, the even-number verses share the same rhyme. In some formats, the first verse will rhyme with the even-number verses. The rhymed words must be on the level tone 平聲. There are two rhymes in Liu’s poem. Lines one and three rhymes on the phoneme [an/ㄢ]. Both “年”and “南,” are second-tone words, therefore, of “rising-level” tone 陽平in theory. Linese two and four rhymes on [ü/ㄩ]. Both “雨”and “許” are third-tone words. The contemporary third tone is considered “oblique/slanting” tone 仄聲, not used in traditional rhymes.

Liu began teaching at Beijing University in 1917. In the short poem, written in the spring of the following year, the young first-time professor eloquently expressed his nostalgia for the South. His vocabulary was simple yet captivating, echoing the elegance of ancient poetry. The linguistic fluidity created a natural musicality.

Listening to the rain all night. . . The poet was most likely alone. The rain, a common weather phenomenon of the South, reminded him that half a year had passed since his arrival in the North. Along with the rain, another growing season would have started in his hometown. In the old orchard, new bamboo shoots would have burst out of the ground impatiently. Other than the excitement of harvesting bamboo shoots, would he also be remembering the musty smell of the moist soil?

Liu’s birthplace Jiangyin of Jiangsu Province is on the southern bank of the Yangtze River. Zhao Yuanren who set the poem to music was a native of Changzhou, located about 30 miles southwest of Jiangyin. His twenty-one-measure setting was a spiritual and linguistic tribute to their southern roots.

From a very early age, Zhao was taught traditional poetry and Chinese Classics in Changzhou dialect by family tutors. Meanwhile, due to his father’s work, the family lived in various northern cities where Mandarin was the commonly spoken language. They moved back to Jiangsu in 1902. Already a teenager, Zhao had a new awareness of his linguistic roots. In his memoir, he testified the impact of this transitional period:

Psychologists tell us that a personality is formed very early in one’s life, maybe before one learns to speak. But so far as I can remember as a non-psychologist, I experienced more changes in myself and in people around me during my second nine years than in any other period of my life. During those years the speech of my environment changed from Mandarin to that of Changchow, a Wu dialect. . .. This was the first time I really felt at home both geographically and linguistically, now that I had learned not only to read, but also to speak in the Changchow dialect.[3]

心理學家說,一個人的性格在早年便已形成,或許在學習說話之前。我並非心理學者,可是據我記憶,在我第二個九年當中,我自己以及圍繞我四周的人們,改變得較我一生其他時期都要多。在這幾年期間,我周圍人講的不再是官話,而是常州話。. . . 在地理上,且在修辭學上而言,這是第一次我真正感覺住在家鄉,我不僅學會唸書,且能講常州話。[4]

Coming from a linguist who spoke multiple Western languages and over thirty Chinese dialects, this statement gave us the insight of Zhao’s intrinsic connection to his native tongue. Unsurprisingly, he used the tune of traditional Changzhou poetic chanting as the foundation of “Listening to the Rain.”

__Changzhou Poetic Chanting 常州吟唱

The versification of the traditional Chinese poetry was rooted in tonal patterns. Each poetic form has, therefore, a distinct pitch contour which gradually evolved into melodic phrases. For thousands of years, poetic chanting made it easy for children to memorize verses and enhanced the appreciation of sounds and sentiments for elite scholars. Since regional dialects have their own tonal systems, poetic changing practices diverge accordingly.[5]

Zhao Yuanren was first introduced to Tang poetry by his mother and, at the age of four, continued learning from family tutors. In Lesson 22 of Mandarin Primer Records 國語入門 (1955), Zhao, as one of the interlocutors, retold his experience and chanted two poems—”Mooring by the Maple Bridge 楓橋夜泊” by Chang Chi 張繼 and “Night Thought 靜夜思” by Li Po 李白.[6] He used the same poems in “Tone, Intonation, Singsong, Chanting, Recitative, Tonal Composition, and Atonal Composition in Chinese” (1956) to demonstrate the stylistic differences between chanting the “antique poem” and “metric poem.” Two versions of melodic transcriptions were given to each poem to show the variants of chanting the same words.[7] The second versions are in the singsong 唱讀 style, following the tones of each word closely and with less movements between words.[8]

“Mooring by the Maple Bridge 楓橋夜泊,” 7-character metric poem, version 1[9]

“Mooring by the Maple Bridge 楓橋夜泊,” 7-character metric poem, version 2

“Night Thought 靜夜思,” 5-character antique poem, version 1

“Night Thought 靜夜思,” 5-character antique poem, version 2

“常州吟詩的樂調十七例 Seventeen Examples of Melodies for Chanting Poetry in the Ch’angchow (Kiangsu) Dialect,” published in 1961, was a much more extended and systematic documentation and examination of Changzhou chanting, encompassing various styles of poetry.[10] In the conclusion, Zhao summarized the differences between the “antique” and “metric” styles:

- The antique style is lower in pitch.[11]

- The antique style is faster than the metric style.

- The antique style is more rhythmic, and the metric style is more rubato.[12]

- The antique style is more rhythmic than the metric. It is, nevertheless, less regular than ordinary music. Therefore, it is not always appropriate to assign the melodies to strict meters and time signature.

- The geographical/regional differences are more obvious in the antique style.[13]

- In general, the melodies of the Changzhou chanting are in major mode (or Ionian). The metric style mostly ends on the third degree, which gives an effect of the Phrygian mode.

In April 1971, during the third conference of Chinese Oral and Performing Literature (CHINOPERL), along with prose literature—both classical and popular—which he discussed in 1956 essay, Zhao recited these seventeen poems. His presentation as well as the northern style chanting by Cheng Xi 程曦 were recorded by Liu Chun-Jo 劉君若, a professor at the University of Minnesota. In 2009, Zhao Yuanren Cheng Xi yin song yi yin lu 趙元任程曦吟诵遗音錄, a compilation of the original recordings as well as related writings edited by Qin Dexiang 秦德祥, were brought to light.[14]

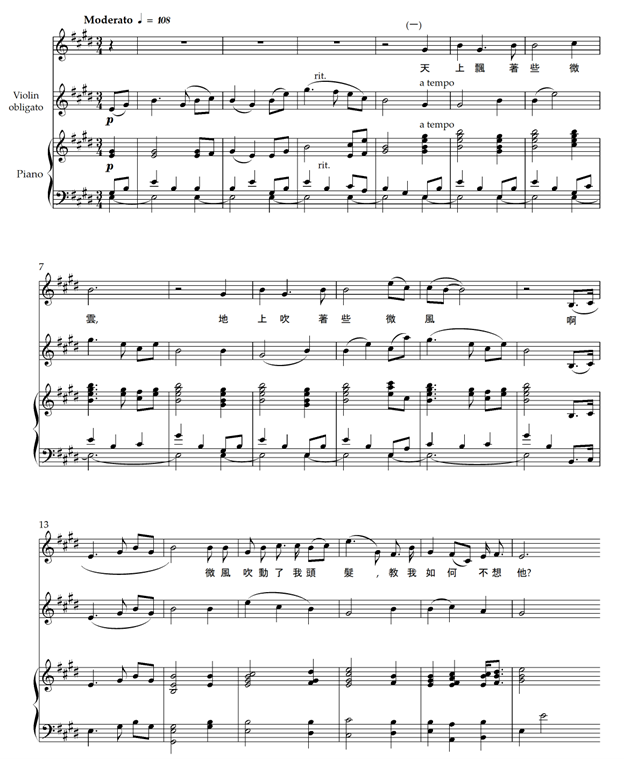

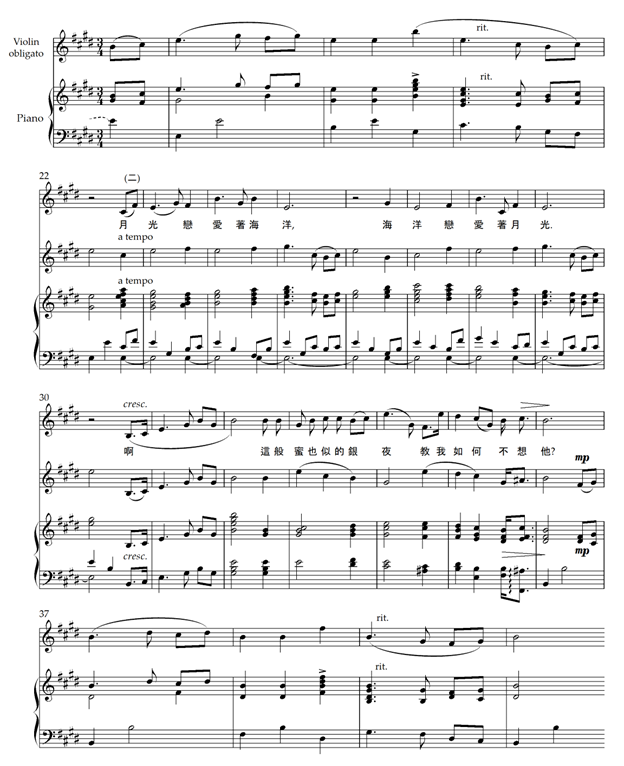

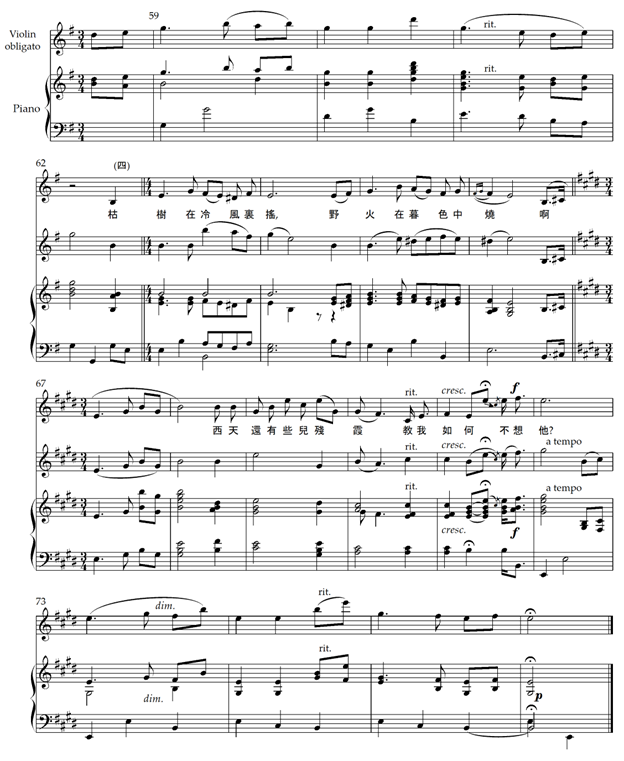

__ “Ting yü 聽雨” (1927)

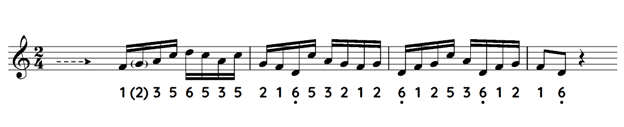

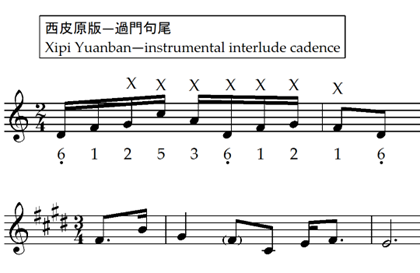

Zhao’s setting of “Listening to the Rain” is based on the melody of the antique style chant: [15]

A straightforward chanting of these words takes less than twenty seconds. Zhao humorously commented that there would not be enough rain for new bamboo shoots to pop up in the old orchard. So, he added rhythm details, and set the tempo to “Andante ♩=72.”

While maintaining the narrow vocal range of a tenth in his setting, he allowed wider melodic movements in his setting. In verses three and four—mm. 13 – 21, the vocal lines swung back and forth between the lowest pitch to the highest one. This gesture not only heightened the emotional content but also enhanced the linguistic ebb and flow—the intonation of the Chinese language, which Zhao explained in “Tone, Singsong and Composition in Chinese” (1956):

The actual pitch movement of Chinese speech is the algebraic sum of tone and intonation. If an upswing of a sentence coincides with a rising tone, the rising tone will be higher than usual. If a falling intonation coincides with a rising tone, the rising tone will rise less or be made at a lower register than the first part of the sentence. . .. [16]

In the “Tonal composition” section of the above-cited article, Zhao addressed the differences between singing a song and chanting:

Singing a song differs from chanting in that the singer is expected to sing the same tune to the same song on repetition. The fixed tune may have been deliberately composed by a composer or simply have grown from tradition into one or possibly several alternate versions[.] . . .Such a composition differs from chanting in that once it is on paper, the singer is bound to follow what has been set down and is not free to improvise on the basis of tones, as he goes along. Since, however, much of Chinese music is written without indication of embellishments, the singer is allowed and expected, within limits of good and bad taste, to introduce grace notes of his own to the main melody. Some of the grace notes follow conventional musical usage, such as free addition of a note by way of an échappée. Others are added in order to “smuggle in” the tone, if note already suggested in the main melody. The effect of smuggling in the tones is that of clearer “diction” (in the singing-lesson sense), since phonemic tone is part of the constituent elements of the word.[17]

Clearly, a proper delivery of “Ting yü,” showcasing the tonal elements of the text while faithful to the notated score, requires a comprehensive understanding of its linguistic and musical background. Technically, an operatic approach should be avoided.

For the pianist, Zhao’s recommendations were simple: Treat the eighth-note motive like rain drops; think of Chopin’s Prelude, Op. 28, No. 15. In performance, it is crucial to not sound like a musical drone.[18] Instead, the accompaniment should allow the singer spontaneity in tempo and phrasing.

[1] 江南 [jiang nan], literally “river”-“south,” refers to the geographic area south of Yangtze River.

[2] https://goldfishodyssey.com/2021/02/21/chinese-poetry-vii-tang-poetry/

[3] Zhao Yuanren, “Yuan Ren Chao’s Autobiography: First 30 Years, 1892-1921: Part II, My Second Nine Years,” in Zhao Yuanren quan ji 趙元任全集, (Beijing: Shang wu yin shu guan 商務印書館 2002-), Vol. 15, Part I, 401-403.

There are two types of Changzhou dialect: the gentry talk 鄉紳話, spoken by elites, and the street talk 街談, spoken by the commoners. Their tonal systems are slightly different. Zhao was not aware of the street talk until he was nine years old. See “The Changchow Dialect,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 90, No. 1 (Jan. – Mar., 1970), 49-50.

[4] “趙元任早年自傳: 第二部分, 第二個九年,” in ibid., Part II, 824-825.

[5] Recitations/chanting of poems in various dialects can be found on YouTube.

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cmf50VCRpcQ Mandarin Rimer Records, 1955, New York, FP8002 Folkways Records, Band 6A, Track 3.

The chanting of the first poem begins at 3:11 of the video and ends at 3:33; the second one, 3:56 to 4:08.

See Smithsonian/folkways.si.edu/yuen-ren-chao/the-mandarin-primer for the original liner notes.

In this five-minute lesson, Zhao played multiple characters each spoke a different dialect: The Waiter in Nanjing dialect; Speaker A, Chongqing dialect; Speaker B, Mandarin; and the tea-egg vender, Shanghainese.

[7] Chao Yuen-Ren, “Tone, Intonation, Singsong, Chanting, Recitative, Tonal Composition, and Atonal Composition in Chinese” in For Roman Jakobson: Essays on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday, 11 October 1956 (Mouton, The Hague, 1956), 52-59.

Recitations by Qin Dexiang 秦德祥, based on these transcriptions, were included in Zhao Yuanren Cheng Xi yin song yi yin lu 趙元任程曦吟诵遗音錄 [Recordings of chanting and recitations by Zhao Yuranren and Cheng Xi], compiled by Qin, (Beijing: Shang wu yin shu guan, 2009). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_87LWMWYLfo&t=144s

[8] “Tone, Singsong, and Composition in Chinese” (1956), 54-56. The abbreviated title was taken from the original publication cited above.

劉紅霞, “由《趙元任程曦吟誦遺音錄》看中國傳統詩文吟誦”, 中國孔子網, August 28, 2019, http://www.chinakongzi.org/zt/4189/lw/201908/t20190828_199657.htm

[9] The original transcription of this version was in quadruple time throughout. For western-trained ears, the stresses and the word movements do not always match. I modified the time signatures according to Zhao’s chanting.

The seven word-tones are:

Number Tone class Tone value on the 5-point scale

1 Upper Even 陽平 23:

2 Lower Even 陰平 14:

3 Upper Rising 陽上 55:

4 Upper Going 陽去 524:

5 Lower Going 陰去 24:

6 Upper Entering 陽入 5:

7 Lower Entering 陰入 23:

See Tone_letter#Chao_tone_letters_(IPA)_Wiki for the 5-point tone scale. In versification, the two even tones are considered level tones. All other tones are oblique. Tone indicators were missing for the final words of verses two and four.

[10] “常州吟詩的樂調十七例” in Qing zhu Dong Zuobin xian sheng liu shi wu sui lun wen ji 慶祝董作賓先生六十五歲論文集 [Studies presented to Dong Zuobin on his sixty-fifth birthday], (Taipei: Zhong yan yan jiu yuan Li shi yu yan yan jiu suo 中央硏究院歷史語言硏究所, 1961): 467-471.

The English version is included in Zhao Yuanren quan ji 趙元任全集, Vol. 11, Part II, 567-572.

[11] The pitches were relative to the chanter’s voice and not absolute.

[12] Here, the word “rhythmic” seemed to be used to indicate the more syllabic style with straightforward movement.

[13] The fixed tonal patterns in the metric style contribute to the relative uniformity. On this point, the English version diverge slightly from the Chinese original. Zhao mentioned the civil service exams was a possible reason for the uniformity.

[14] See note 7.

The sound files also include Qin Dexian’s reading of the opening verses of Chang Hen Ge 長恨歌 [Song of Everlasting Regret], a poem of the seven-character ancient style, by Bai Juyi 白居易 (772-846).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_87LWMWYLfo&t=122s, 2:00-2:17.

Zhao Yuanren first used the excerpt to explain the differences between musical phrases and literary phrases in his article “On Time” 說時 in Kexue 科學 [Science, monthly] , Vol. 2, 1916. The segment on “Musical Time” is excepted in Zhongguo jin dai yin yue shi liao hui bian, 1840-1919 中國近代音樂史料匯編 1840-1919, Chang Jingwei 張靜蔚 edited, Ren min yin yue chu ban she人民音樂出版社, Beijing 1998, 261-274. In 1956, Zhao was hoping to record the long narrative poem. Overwhelmed by nostalgic emotion, he gave up the attempts in tears. The incident was noted in his diary and retold by his second daughter.

[15] In his original numerical notation, the composer, while giving no time signature, used bar lines dividing each verse into 2-2-2-1 pattern. From his recorded chanting, we understand that such strict division does not exist in practice. Therefore, when converting the melody to staff notation, I removed most bar lines. A sample reading of this particular melody in Changzhou dialect by Qin Dexian was included in the appended segment of his 2009 edition. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_87LWMWYLfo&t=122s, 1:45-2:00.

[16] “Tone, Singsong and Composition in Chinese,” 53.

[17] Ibid., 57.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drone_(sound)