The setting of “The Great River Flows Eastwards 大江東去” (Shu Shi 蘇軾, 1082) by Liao Shangguo 廖尙果 was written in 1920 while the composer was studying law in Germany. After returning to China in 1922, Liao held high-powered administrative and military positions until his participation in the failed communist Guangzhou uprising in 1927.[1] Wanted by the Nationalist government, he fled to Shanghai where, with helps from Xiao Youmei 蕭友梅, he became involved in music education, critical writing, and publishing. In 1930, “Da jiang dong qu 大江東去” was published by his firm X Bookstore, under the pen name Qing Zhu 青主.[2] In the back-cover note, he gave an anecdotal genesis of the song:

In the summer of 1920, while vacationing in the countryside, adventurously, he and his friend rowed out to the nearby lake in a small boat on a thundery night. He returned to the cottage feeling exhilarated. Listening to the sounds of thunder and rustling pine tree, he conceived the musical motive of the song. After a night of contemplation, he sat in front of the piano; made some modifications to Su Shi’s “Da jiang dong qu;” and set it to the melody.[3]

Looking beyond this striking narration of an impulsive young man finding creative ideas in tempestuous surrounding, “Da jiang dong qu” was in fact an amalgamation of Qing Zhu’s literary knowledge, musical training, and aspirational reflections. Rather than a spontaneous outburst of inspiration, its creation was a long-time-coming.

Born into a literary family in 1893, Qing Zhu was fond of learning and showed interest in music since his early years. In 1908, he enrolled in the junior school of Whampoa Military Academy where he played trumpet in the marching band. Reform-minded, he participated in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution 辛亥革命, overthrowing the Qing Dynasty. For his contribution, he received governmental grant to study military science in Germany in 1912. However, the newly established Beiyang government 北洋政府[4] objected to young people studying military strategy abroad. Under the pressure, he soon switched to studying law. While in Berlin, he also studied music theory and learned to play the piano, violin, and flute.

In 1919, the political and cultural changes in China climaxed with the student demonstrations on May Fourth.[5] It would not be difficult to imagine how such powerful movement would have impacted a young person of great political aspirations despite the geographical distance. By the summer of 1920, Qing Zhu had completed his coursework.[6] How proud he must have felt reaching such a milestone in life; how eager he must have been to utilize his knowledge and to serve his country, a new democracy embroiled in internal conflicts as well as external threats.

Well-versed in Chinese literature, Qing Zhu would have been familiar with “The Great River Flows Eastwards,” written by Su Shi, two years after he was banished to Huanzhou 黃州 for his political ideology.[7] Upon visiting the Red Cliffs by the Yellow River, astonished by the striking scenery, the poet lamented the fugitiveness of lives in contrast to the perpetuity of the water. Reminiscing the greats from the Three Kingdoms and their heroic acts during the Battle of the Red Cliff, he praised the characters and strategies of Zhou Yu 周瑜. Yet, no bravery or talent could stand the test of time. Life was but a dream.

Indirectly, Su Shi hinted his own desire to achieve greatness while resigning to the transience of life. It should have been no surprise that Qing Zhu found inspirations in this poem, especially after an adventurous boat trip.

—Lyrics

大江東去,浪淘盡、

da4 jiang1 dong1 qu4, lang4 tao2 jin4. . .

ㄉㄚˋ ㄐㄧㄤ ㄉㄨㄥ ㄑㄩˋ, ㄌㄤˋ ㄊㄠˊ ㄐㄧㄣˋ

千古風流人物。[8]

qian1 gu3 feng1 liu2 ren2 wu4.

ㄑㄧㄢ ㄍㄨˇ ㄈㄥ ㄌㄧㄡˊ ㄖㄣˊ ㄨˋ

故壘西邊,人道是、

gu4 lei3 xi1 bian1, ren2 dao4 shi4:

ㄍㄨˋ ㄌㄟˇ ㄒㄧ ㄅㄧㄢ, ㄖㄣˊ ㄉㄠˋ ㄕˋ

三國周郎赤壁。

san1 guo2 zhou1 lang2 chi4 bi4.

ㄙㄢ ㄍㄨㄛˊ ㄓㄡ ㄌㄤˊ ㄔˋ ㄅㄧˋ

亂石崩雲,驚濤裂岸,捲起千堆雪。

luan4 shi2 beng1 yun2, jing1 tao1 lie4 an4, juan2 qi3 qian1 dui1 xue3.

ㄌㄨㄢˋ ㄕˊ ㄅㄥ ㄩㄣˊ, ㄐㄧㄥ ㄊㄠ ㄌㄧㄝˋ ㄢˋ, ㄐㄩㄢˊ ㄑㄧˇ ㄑㄧㄢ ㄉㄨㄟ ㄒㄩㄝˇ

江山如畫,一時多少豪傑。

jiang1 shan1 ru2 hua4, yi4 shi2 duo1 shao3 hao2 jie2.

ㄐㄧㄤ ㄕㄢ ㄖㄨˊ ㄏㄨㄚˋ, ㄧˋ ㄕˊ ㄉㄨㄛ ㄕㄠˇ ㄏㄠˊ ㄐㄧㄝˊ

*****************

遙想公瑾當年,小喬初嫁了,雄姿英發。

yao2 xiang3 gong1jin3 dang1 nian2, xiao3qiao2 chu1 jia4 liao3, xiong2 zi1 ying1 fa1.

ㄧㄠˊ ㄒㄧㄤˇ ㄍㄨㄥ ㄐㄧㄣˇ ㄉㄤ ㄋㄧㄢˊ, ㄒㄧㄠˇ ㄑㄧㄠˊ ㄔㄨ ㄐㄧㄚˋ ㄌㄧㄠˇ,

ㄒㄩㄥˊ ㄗ ㄧㄥ ㄈㄚ

羽扇綸巾,談笑間、

yu3 shan4 guan1 jin1, tan2 xiao4 jian1. . .

ㄩˇ ㄕㄢˋ ㄍㄨㄢ ㄐㄧㄣ, ㄊㄢˊ ㄒㄧㄠˋ ㄐㄧㄢ

強虜灰飛煙滅。

qiang2 lu3 hui1 fei1 yan1 mie4

ㄑㄧㄤˊ ㄌㄨˇ ㄏㄨㄟ ㄈㄟ ㄧㄢ ㄇㄧㄝˋ

故國神遊,多情應笑我,早生華髮。

gu4 guo2 shen2 you2, duo1 qing2 ying1 xiao4 wo3, zao3 sheng1 hua2 fa3.

ㄍㄨˋ ㄍㄨㄛˊ ㄕㄣˊ ㄧㄡˊ ㄉㄨㄛ ㄑㄧㄥˊ ㄧㄥ ㄒㄧㄠˋ ㄨㄛˇ ㄗㄠˇ ㄕㄥ ㄏㄨㄚˊ ㄈㄚˇ

人生如夢, 一尊[9]還酹江月。

ren2 sheng1 ru2 meng4, yi4 zun1 huan2 lei4 jiang1 yue4.

ㄖㄣˊ ㄕㄥ ㄖㄨˊ ㄇㄥˋ ㄧˋ ㄗㄨㄣ ㄏㄨㄢˊ ㄌㄟˋ ㄐㄧㄤ ㄩㄝˋ

In the back-cover note, Qing Zhu mentioned that he modified Su Shi’s wording slightly without providing details. His lyric followed closely the version from Yu ding ci pu 御定詞譜 included in the “Ji” 集section of Siku Quansu 《四庫全書》.[10] It was a version most widely known to readers of the last centuries.

In phrases five and six, he changed the words “穿空. . . 拍岸” ([chuan1 kong1. . .pai1 an4/ㄔㄨㄢ ㄎㄨㄥ. . . ㄆㄞ ㄢˋ]; piercing the sky. . . slapping the shoreline) to “崩雲. . .裂岸” ([beng1 yun2. . .lie4 an4/ㄅㄥ ㄩㄣˊ. . . ㄌㄧㄝˋ ㄢˋ]; bursting the clouds. . . splitting the shores), referencing a version from Rongzhai Xubi 《容齋續筆》, dated c.1193, where the text read: “崩雲. . .掠岸” ([beng1 yun2. . . lüe4 an4/ㄅㄥ ㄩㄣˊ. . . ㄌㄩㄝˋ ㄢˋ]; bursting the clouds. . . sweeping the shores).[11] Qing Zhu’s edited text enhanced the image and sounds of these verses.

In the second part of the poem, the fifth phrase reads “談笑處” ([tan2 xiao4 chu4 /ㄊㄢˊ ㄒㄧㄠˋ ㄔㄨˋ]; as casual chats took place) in both Yu ding ci pu and Rongzhai xubi. Qing Zhu used “談笑間” ([tan2 xiao4 jian1/ㄊㄢˊ ㄒㄧㄠˋ ㄐㄧㄢ]; amid casual chats), appeared in Ci zong 《詞綜》of 1744. [12] In phrase six, instead of 檣艣/檣櫓 ([qiang2 lu3/ㄑㄧㄤˊ ㄌㄨˇ], masts and sculls) as appeared in most sources, Qing Zhu chose the homophone 強虜 (barbaric enemies). For the penultimate phrase, rather than 人間如寄 ([renjian ru ji/ㄖㄣˊ ㄐㄧㄢ ㄖㄨˊㄐㄧˋ], “the mortal world is like a temporary shelter”) or 人間如夢 ([renjian ru meng/ㄖㄣˊ ㄐㄧㄢ ㄖㄨˊ ㄇㄥˋ], “the mortal world is like a dream”) in some sources, he used “人生如夢” ([rensheng ru meng/ㄖㄣˊ ㄕㄥ ㄖㄨˊ ㄇㄥˋ], “Life is like a dream. . .”).

Special attention should be given to the pronunciation of the following words:

•Tone sandhi should be applied to 捲起 in verse nine—both in the third tone, resulting in [juan2 qi3/ㄐㄩㄢˊ ㄑㄧˇ].

• Literary pronunciation [liao3/ㄌㄧㄠˇ] should be used for the last character in 小喬初嫁了, verse two of the second part.

• In verse four, part two, the word 綸 is pronounced [guan1/ㄍㄨㄢ], meaning black head scarf, and not [lun2/ㄌㄨㄣˊ].

• Literary pronunciation [huan2/ㄏㄨㄢˊ] should be applied to 還 in the final verse.

__Tone patterns, expressions, and structure

Tone pattern (平仄) along with rhyme scheme were two crucial elements of traditional Chinese poetry, especially for the ci 詞 poems which were governed by cipai 詞牌—fixed tune structures.[13] As the editor of Yue yi 樂藝, a quarterly journal of the National Conservatory of Music—the predecessor of Shanghai Conservatory of Music, Qing Zhu included, for its inaugural issue in April of 1930, an article “聲韻是歌之美” (Tone patterns are the beauty of songs), written by the librettist/poet Yi Weizhai 易韋齋.[14] In his own article “作曲和填詞” (Composing music vs filling in lyrics), he also expressed his deep appreciation for this unique literary feature. However, he vehemently opposed allowing tone patterns to dominate melodic constructs, especially applying the same tune to texts of different characters. [15]

He elucidated in “什麼是音樂” (What is Music):[16]

. . .This thing—tone pattern, . . . when used in poetic art, might have some distinctive attribute. However, when applied in music, it would deprive music of its life. Every Chinese ci of the olden days could be sung. How? Once the music was set to a cipai, you could fill up some verses. No matter whether these verses were majestic or afflicted; joyful or sorrow, you could draw upon the same music to sing them. . . . Why could you sing verses of many different meanings using the same music? Because, in the views of the literati who monopolized music, it should be governed by tone patterns. As long as the verses and tone patterns were not in contradiction, naturally they could be sung to the same music which was also dominated by the tone patterns. Imagine how music, dominated by tone patterns, could find independent existence. For example, you wish to compose a song: When you see the lyrics, since you are restricted by the tone patterns of the verses, how can you compose? Even if you painstakingly put together a song, the kind of work that you pursue can only be called “filling in music,” and never “composing.”

Instead, he advocated a rhetoric approach of conveying the poetic expressions by enhancing the key words in each verse. Chosen based on the contents of the verses, these words would be set to longer notes or higher pitches by the composer. Such emphases were to stimulate the audience’s awareness and to stir up their imaginations and emotions.[17]

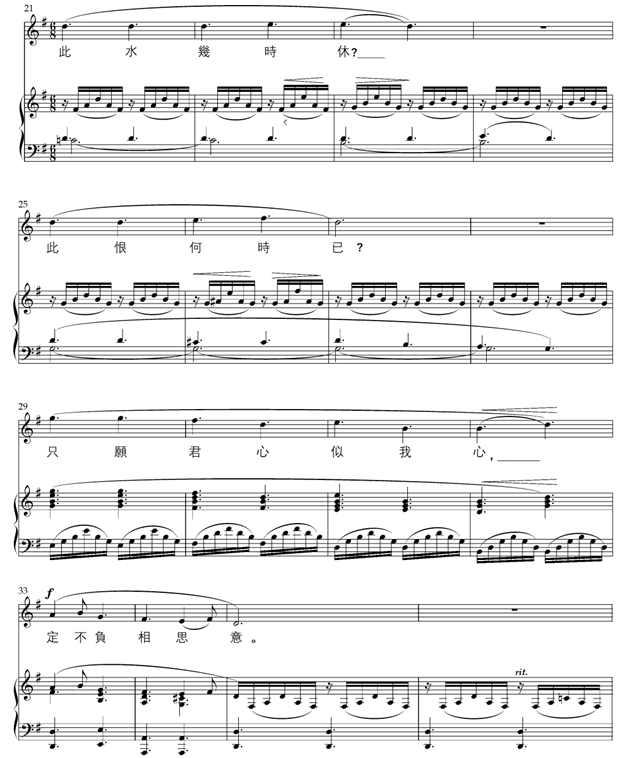

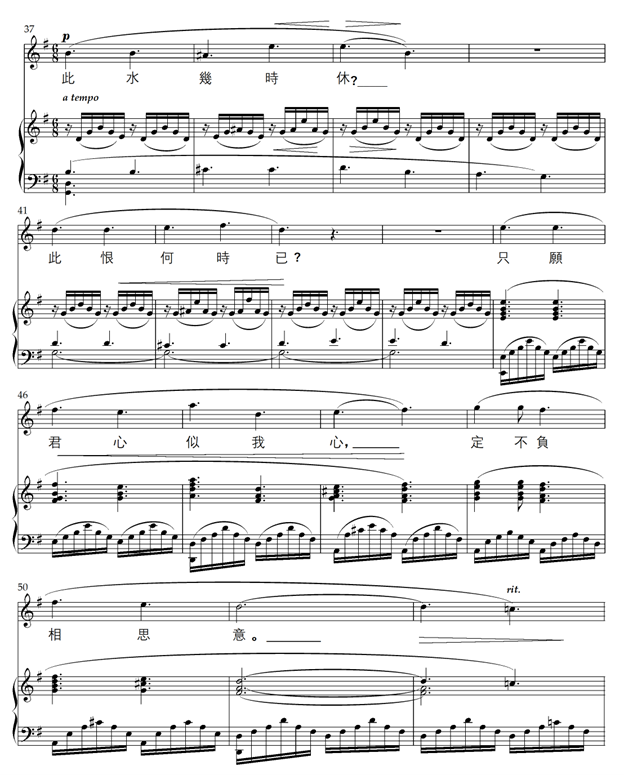

Like many of his contemporaries, he was a firm believer of the superiority of Western music. Modeled after the tradition of German Lieder,“Da Jiang Dong Qu” was a through-composed piece of two contrasting sections, corresponding to the poetic structure, and a coda. The general tonal structure, E minor-E major-E minor, appeared to be very simple and, to a certain degree, predictable. Some detailed harmonic movements, on the other hand, were fugitive and striking.

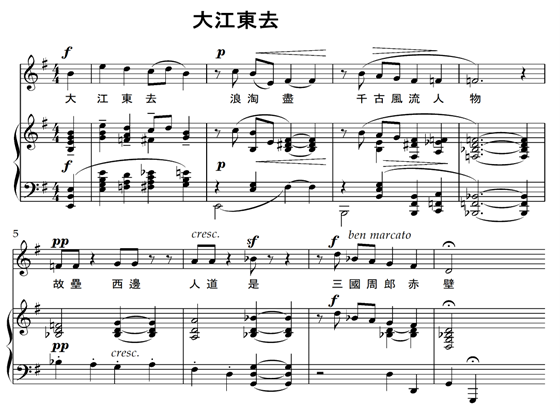

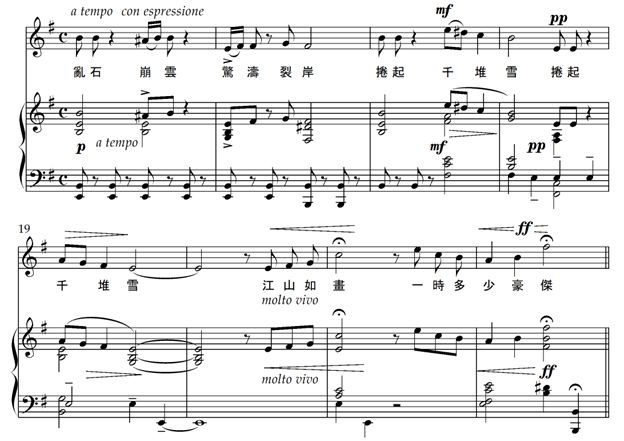

The piece opens with a majestic, upward moving, declamation without introduction. Quickly, the melody and dynamic descend, signifying the dissipation of historical greats. The tonic-dominant harmonic progression is obscured by the chromatic moves in verse three. Thus, the first musical phrase ends in B-flat major—far from the home key. The second musical phrase, moving from B-flat to its relative g minor, starts with inquisitive repeating notes in the vocal line and regains the grandeur with an authentic cadence in g minor.

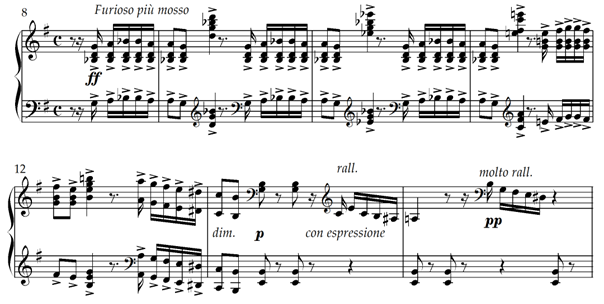

Referencing the battle of red cliffs, in the following phrases, the piano alone depicts the dramatic scenery of fierce battles with fast moving chord and furious sonority, ending with a five-note motif in measure 14 mirroring the melodic line of measures 7 and 8. The six-measure interlude also functions as a tonal bridge, bringing back the opening E minor.

The vocal line returns with broken phrases, parallel to the narrations of verses four and five (mm. 5 and 6). The words 捲起千堆雪 are repeated–the first time rising and the second time falling—depicting the whirling movement. Powerfully, the opening section ends with a half-cadence in e minor, echoing the initial proclamation.

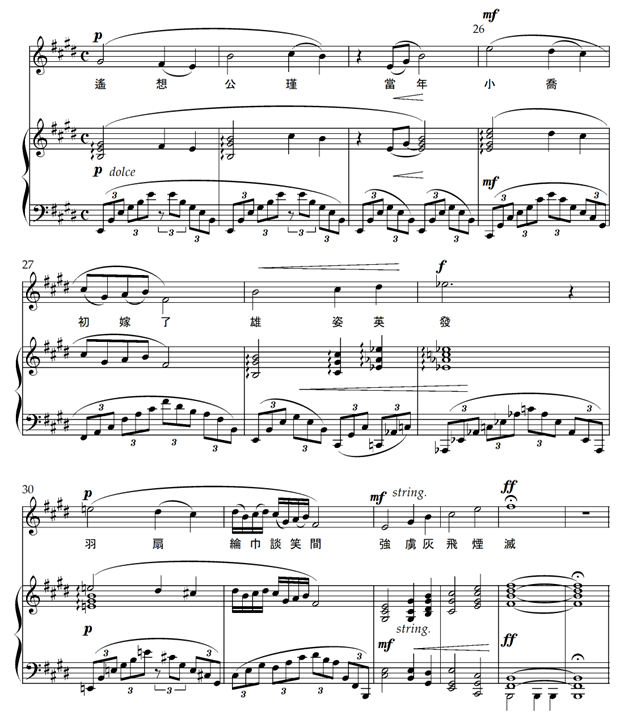

The sudden changes in tonality, dynamics, articulation, and texture marked by a double-barline between measure 22 and measure 23 must be felt and carefully delivered by the singer and the pianist alike. The poet turned from observing the scenery and reminiscing historical events to admiration of his personal hero—Zhou Yu.

Zhou was described to be statuesque and hansom in Records of the Three Kingdoms 三國志.[18] He and the beautiful younger Qiao were considered a match made in heaven. The gentle and flowing musical phrases (mm. 23-29) for verses twelve to fourteen should be presented in an intimate manner. The words 英發 (radiant appearance) were highlighted by a brief harmonic maneuver from E major to A-flat major.

In addition to being a skillful military strategist, Zhou Yu was also known for his musical gift—capable of scrutinizing musical mistakes even after three drinks.[19] Qing Zhu very likely had found a kindred spirit in him. In mm. 30 and 31, we see the easy movement of a feather fan and billowing gown; we hear the casual chattering of quick notes, which led to the climax. The pianist should provide a definitive ending—the total annihilation of the opposing force—with resounding dominant bass in m. 34 and then allowing the sound to fade.

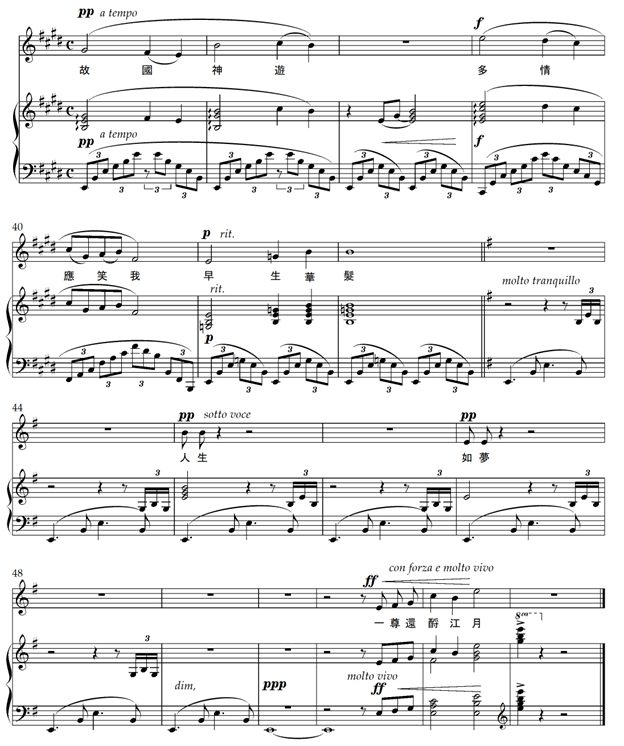

The reflective words of the final verses are matched by the recurrence of the first phrases of the second section. This time, it softens into the minor mode. Then, the ostinato in the piano part, a mantra, brings forward the final abandonment.

—Conclusion

A century had gone by since the creation of “Da jiang dong qu.” It remains one of the most popular vocal works among musicians of Chinese descent. Hopefully, careful studies of the literary and compositional details will expand its popularity to a wider audience.

[1] Liao served as a high court judge of the Beiyang government (北京政府大理院推事) from 1922 to 1924. He then held administrative positions in military organizations, rising from the rank of lieutenant colonel to major general.

[2] Liao used the name 青主Qing Zhu for his musical compositions. A surname Li 黎 was often added for his theoretical and critical writings.

[3]Liáng Màochun 梁茂春, “中國第一首優秀藝術歌曲——青主的《大江東去》” (China’s First Excellent Art Song—Qing Zhu’s ‘Da jiang dong qu’), Music Weekly (音樂週報), January 31, 2003:

“在《大江東去》樂譜的封底附有青主寫的一篇文章——《作者的話》,文中回憶了《大江東去》的產生經過:1920年夏,青主和友人在雷鳴暴雨中划着小艇到湖中作冒險之遊,精神上受到很大振奮。當他回到住所後,’一面聽着外面風雨和松濤的聲音,一面忽得到這首樂歌的動機,思量一夜後,到了明天,吃過早餐,於是坐在鋼琴面前,把昨夜得來的動機,接着蘇東坡那篇大江東去的詞句略為修理一下,隨即把它寫出來,這就是這首樂歌的緣起。’”

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beiyang_government

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_Fourth_Movement

[6] Although Liao claimed that he received Ph. D. in Law from Berlin University, documents showed that he completed and submitted his dissertation at Hamburg University in 1922.

https://katalogplus.sub.uni-hamburg.de/vufind/Record/351412646?rank=1. This would explain why he remained in Germany until 1922.

[7] Chinese-Poetry-X-the-Great-River-Flows-Eastwards-大江東去/goldfishodyssey.com

[8] The rhyming syllables are indicated by underlines.

[9]尊=樽

[10] 《御定詞譜》_(四庫全書本)/卷28#念奴嬌十二體/zh.wikisource.org

[11] 洪邁 Hong Mai, a scholar of Southern Song Dynasty, commented in his “notebook” that a version of the poem, hand-written by [黃]魯直 [Huang Luzhi], differed from the commonly circulated version in several phrases. “詩詞改字“ (“Changing words in shi-ci)”, 《容齋續筆》 卷八, Part 8 of Rongzhai Xubi: “. . . ‘元不伐家有魯直所書東坡〈念奴嬌〉,與今人歌不同者數處: . . . 」,「周郎赤壁」爲「孫吳赤壁」,「亂石穿空」爲「崩雲」,「驚濤拍岸」爲「掠岸」. . .”

中國哲學書電子化計劃,《容齋續筆》, 70-71/147/ctext.org;

《容齋續筆 卷八》/四部叢刊本/zh.wikisource.org;

Hong_Mai_Wiki

[12] 《詞綜‧卷六》/zh.wikisource.org

[13]Chinese-poetry-ix-ci-lyric-verses/goldfishodyssey.com; “The Great River Flows Eastwards” was a ci based on the tune Niannujia 念奴嬌.

[14] Yi Weizhai 易韋齋, “聲韻是歌之美” (Tone patterns are the beauty of songs), Yue yi 樂藝, Vol. 1, No. 1 (April 1930), 46-53.

[15] Qing Zhu, “作曲和填詞” (Composing music vs filling in lyrics), Ibid., 59:

I know well that tone pattern is an idiom that’s uniquely ours. Moreover, I have, since my youth, acquired the habit of curling up and chanting poetry. Even now, whenever I could close myself alone in a room where no one could hear me, I would, based on the fixed tone patterns, recite old-time Chinese poetry and songs. However, it would be fine if I wouldn’t think of music. . .. As soon as I think of music, I simply cannot care for preserving such idiom. Because tone pattern is a proclamation of the death sentence of music.

我很知道音韻是我國所專有的一種國粹, 而且我自小便染上了抱膝長吟的習慣, 直到今日, 遇著可以獨自一個人關起房門, 不會有別人聽見我的聲音的時候, 我有時也會把中國舊日的詩歌詞曲, 按著一定的聲韻念起來. 但是,我不想起音樂則已,我想起音樂來,我便不能夠顧全到這種國粹了,因是 聲韻是宣布音樂的死刑的一樣東西.

[16] Li Qingzhu 黎青主, Yin yue tong lun (General Survey of Music) 音樂通論, (1933, reprint, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore, 1989), 4-5:

聲韻這樣東西, . . . 把牠用在詩的藝術上面,雖然是別有風味,但是把牠應用到音樂裏面,牠便要剝喪音樂的生命了。中國舊日的詞,首首都是可以拿來唱的。怎麼唱?就是有了一個詞牌的音樂之後,你便可以填上一些詞句,不計這些詞句是雄壯,抑或衰澀,是歡樂,抑或愁苦,你都可以依照同一樣的音樂把牠唱出來。. . . 為什麼你可以把好幾樣不同意義的詞句用同一樣的音樂唱出來?因為在包辦音樂的文人看來,音樂是應該受聲韻的支配,祇要那些詞句是和聲韻沒有違背,自可以依照同一樣受聲韻支配著的音樂把牠唱出來。你們試想,音樂受了聲韻的支配,牠那裏還能夠得到獨立的生命呢?比方你要創作一首樂歌, 當你看見那首歌文的時候, 你既然被那首歌文的聲韻限死, 那末, 你那裏還能夠作曲? 你就勉強作出一篇樂歌來, 你這種工作, 亦祇可以說是填曲, 決不可以說是作曲.

[17] Qing Zhu, “作曲和填詞” (Composing music vs filling in lyrics), 59-68.

[18] 《三國志》, 卷54: 「瑜長壯有姿貌。」

[19] 瑜少精意於音樂。雖三爵之後,其有闕誤。瑜必知之,知之必顧,故時人謠曰:「曲有誤,周郎顧。」