Lots of things happened in the months before I turned 13. I was accepted to Wesley Girls’ High; I was anxiously getting ready to leave home. During this transitional period, Prof. Wu sent me to work with Ms. Lin Pai-Ho (林百合) a well-known pedagogue. A successful teacher of her own right, Ms. Lin was close friends with many other teachers. She knew their technical and stylistic preferences well. Henceforth she became the go-to person when another pair of ears and hands were needed.

Ms. Lin came from a musical family. Two of her sisters were also piano teachers. A tall lady, when standing by the piano, she always seemed like a giant statue towering over me. Even with big glasses softening her facial features, there was still a seriousness about her. Yet, even back then, I knew that she cared about all her students deeply.

In the years that I studied with her, Ms. Lin moved a few times. Every apartment that she lived in had a few small rooms where upright pianos were placed for students to practice or warmup for lessons. From time to time, Ms. Lin would get tied up with other students’ need and forgot that I was still practicing and waiting. It was in those little rooms, facing the piano alone for long hours, that I gradually figured out how my fingers and arms worked. I graduated from lifting fingers to playing scales; from simple pieces to more demanding works.

Knowing that I had limited time to practice at school during the week, Ms. Lin often had me over to do some extra work on weekends. Her goal was to set me on the right path so I could eventually return to working with Prof. Wu. She was patient and very detail-oriented. Still, my slow progress often frustrated her. Whenever she asked me if I was serious about continuing, I knew that I must work harder—not so much about spending more time at the keyboard, but more about working correctly.

I learned the importance of tenacity and organization in those years. Listening to the sounds of other students playing through the doors, I knew there were many kids more talented than I was. I understood that, in order to be competitive, I must work effectively. Studying music became a conscious choice and an enterprise for me.

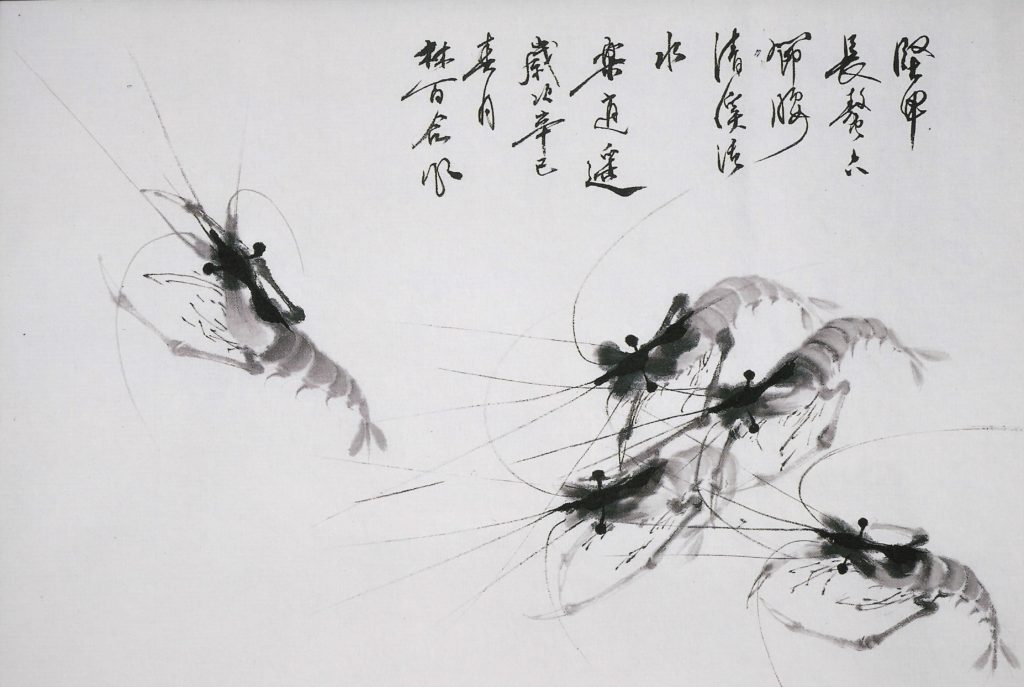

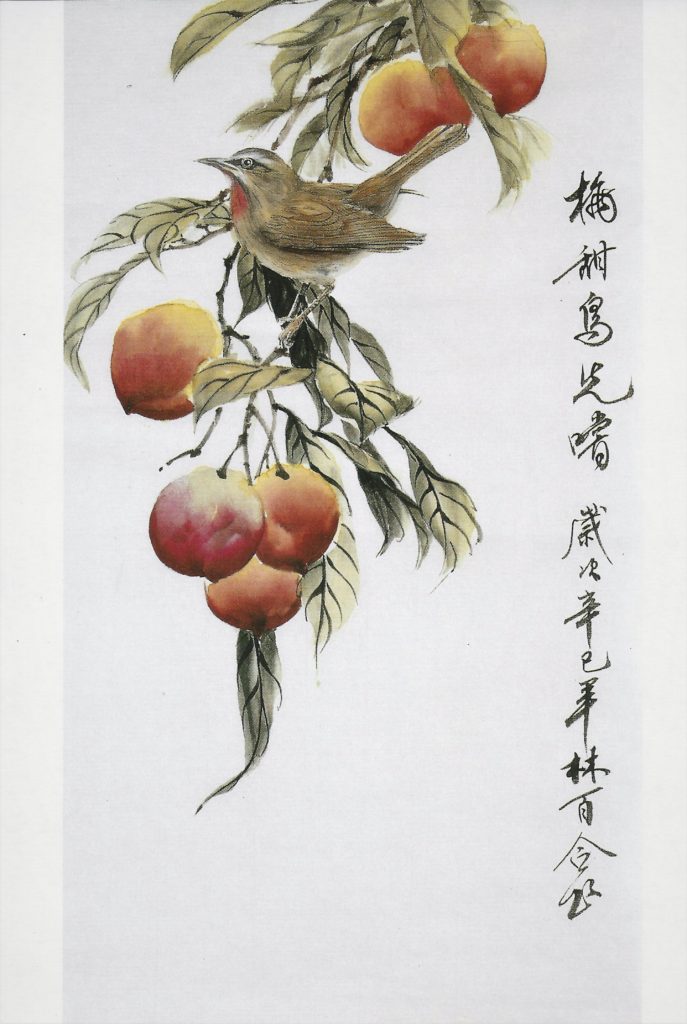

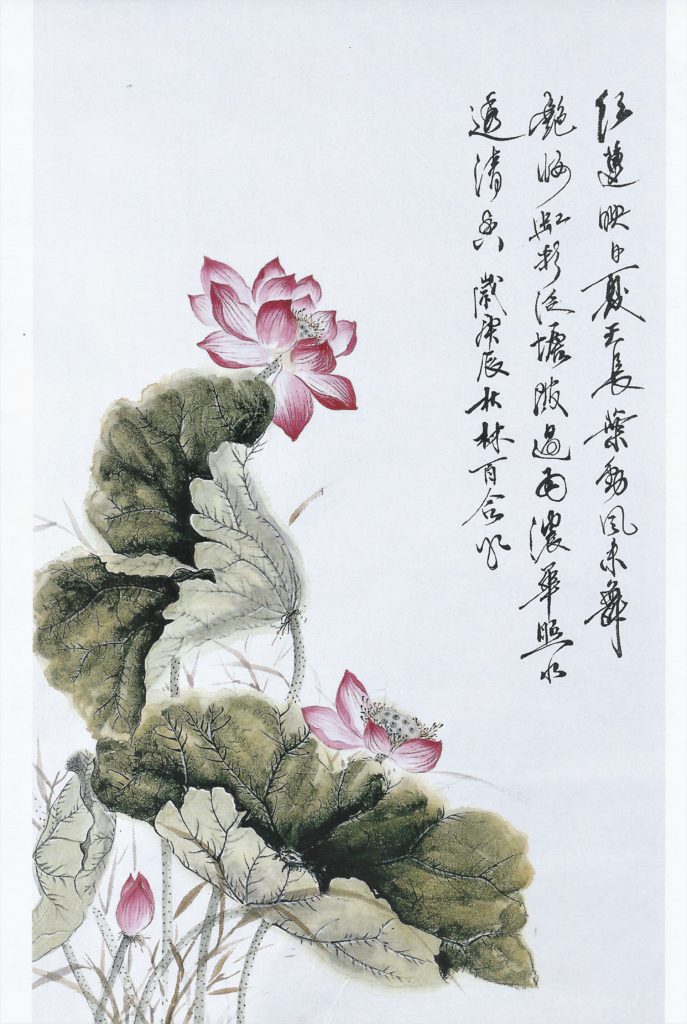

I remained in contact with Ms. Lin years after coming to the States. After retiring, she picked up Chinese calligraphy and painting. One holiday season, I received a collection of postcards with her artworks. From time to time, I would pull these cards out of my drawer and imagine the beautiful hand movements that created them.