New York subway lines are marked by numbers (1 to 7) and letters.[1] Old-timers also identify the lines by colors (blue, red, green, yellow. . .) and their routes (8th Ave. line, 7th Ave. line, etc.). The lifeline for my neighborhood is the blue line along 8th Avenue. Several stations on my line are modernized and beautified with new artworks. While the art installations on the Upper East Side are about people, the ones on the Upper West Side are about neighborhoods and heritage. Two of them stood out:

“Parkside Portals” by Joyce Kozloff at West 86th Street and Central Park West Station are mélanges of glass and ceramic mosaics.[2] Looking out from a fast-moving train, they are kaleidoscopes of astonishing colors and shapes; looking from a distance on the platform, they almost have the characteristic of graffiti; looking from a few feet away, they are composites of various elements, each represents an aspect of environments around Upper West Side and Central Park using different materials.

The four larger installations are frames on two sides by aerial views of Central Park and the Upper West Side, inspired by images of Google Earth and reproduced on painted titles—sceneries from each season and from different directions. The center segments, made of ceramic mosaics, have individual themes: One is the landscape of the Conservatory Garden at Central Park, with flowering trees in the background; a few are panels of beaux-art architectural designs; and, most interestingly, one has a map of Seneca Village, showing the dates 1825 to 1857 and the area from West 82nd St. to West 86th—a reminder of the history and the development of the city.[3]

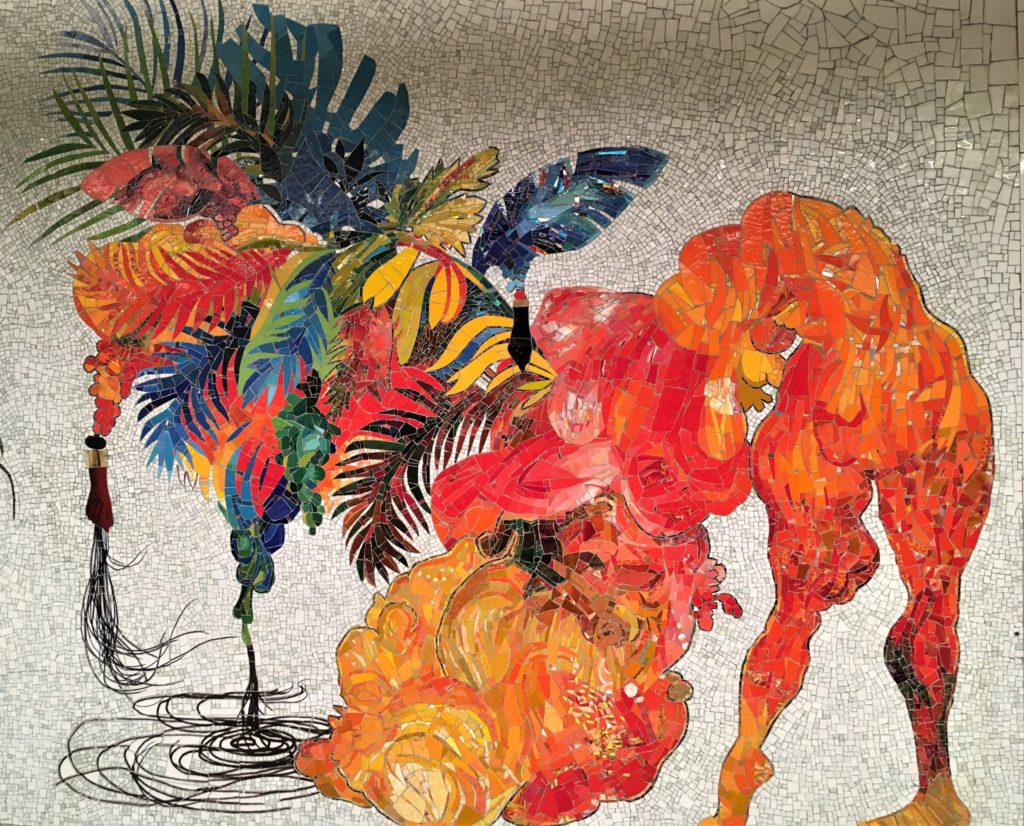

Much further uptown at West 163rd and Amsterdam Ave. Station, Firelei Báez, “Ciguapa Antellana, me llamo sueño de la madrugada (who more sci-fi than us)”[4] is the most cultural-specific creation among the new subway art installations. The station is located in Washington Heights, a neighborhood first attracted German and Eastern European Jews during WWII, and, later, as the younger Jewish generations moved out, immigrants from the Caribbean—Puerto Rico, Cuba and Dominican Republic. Several thematic elements jump out at the viewers: Sugar canes, plantain tress/fruits and trumpet vines represent plants of Caribbean and North America; fists, symbol of Black Power (I noticed a few hamsa hands among them); azbache, black and red; and the mystical feature ciguapa.[5] For viewers unfamiliar with the cultural background of these figures, the vibrant colors of the display brighten up the station; for the immigrant communities, they are celebrations of heritage.[6]

Like most residents of the northern end of Manhattan, I usually rush in and out on the express A train. The beautiful art installations are all on the local stations on the C line. Is it MTA’s way of telling everyone to slow down and take a moment to enjoy life?

[1] Before the establishment of Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the lines were run by various independent companies and thus different naming systems.

[2]2019: Parks Portals

[3]

Seneca Village was a settlement of free African American. It spanned

south-to-north from W. 82nd to W. 89th, and east-to-west from 7th Ave. to 8th Ave. For those who are not familiar with New York Streets, the Avenues are marked by numbers from east to west—1 to 12. 8th Ave., which marks the western side of Central Park, becomes Central Park West above the 59th Street. Seneca Village was within the designated area for Central Park and was torn down during the construction of the park. Seneca_Village_Wiki

[4]

The direct translation of the title is “Ciguapa Antellana, I am called dream of the dawn. . .”.

[5] origin of ciguapa

[6]Craving Spring?